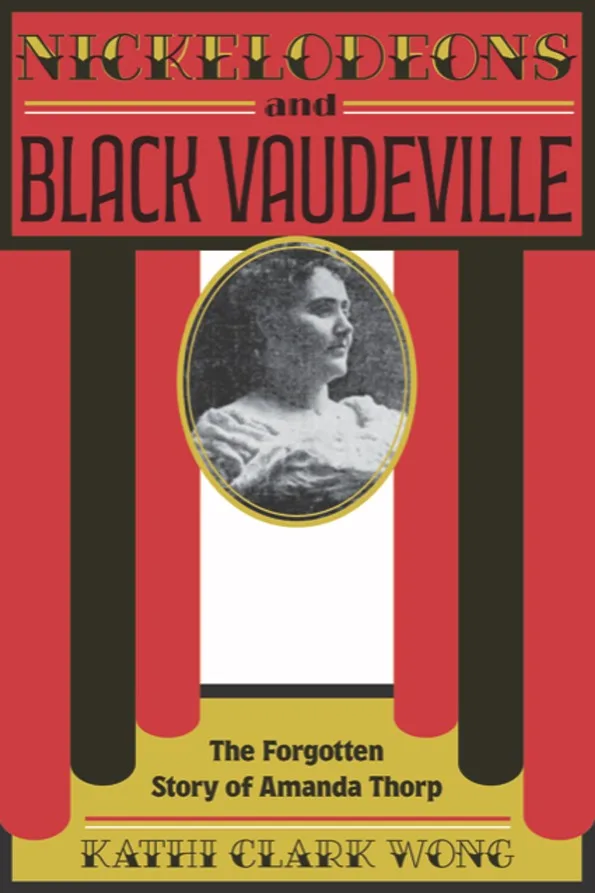

When friends ask what led to her debut book, “Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp,” author Kathi Clark Wong explains that it happened by accident.

Wong has always loved old buildings, and since moving with her husband to Richmond six years ago, she’s enjoyed ours. Not one to waste much time on social media, she runs her own website (www.richmondnarratives.com), which she notes is less interested in the famous historical figures, or movers and shakers, than in “the moved and shaken,” as she puts it. Wong does follow a few special interest groups on Facebook, she admits, which is where a question arrived one day from a woman about a property at 18 W. Broad St. “I told her I’d poke around a bit and see what I can find,” Wong says. “And what I found was Amanda Thorp.”

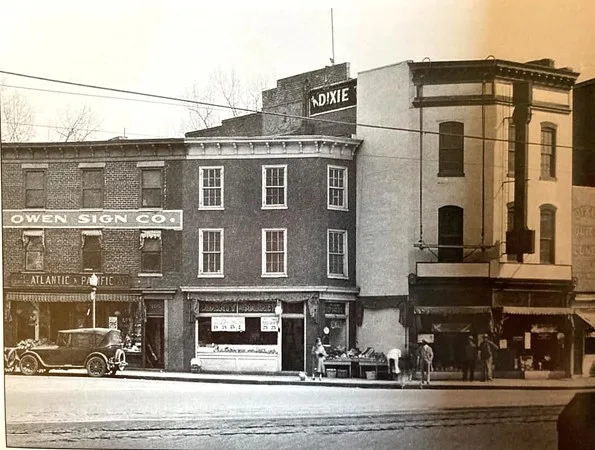

At the start of the 20th century, Thorp was one of very few women entrepreneurs working in the nation’s fledgling movie business. Wong quickly learned that the building at 18 W. Broad St. was the former location of the Dixie Theater, Richmond’s first silent movie nickelodeon, which Thorp launched in 1908.

“If you think about those early movies being like TikTok with the sound turned off, I think it shows the appeal,” Wong says. “Those early movies were just about the same length as TikToks, and they had subtitles written across them, again, just like many TikToks. But you couldn’t watch the early films on a device in your pocket, you had to go to one of the nickelodeons and sit there among another hundred or so people, everyone sweating in the humidity and throwing peanut shells on the floor.”

Thorp, a white woman, relocated from Ohio to Richmond, where she quickly realized the potential for providing entertainment for Black audiences from nearby Jackson Ward. She converted the Dixie to all-Black patronage (yes, it’s a problematic name, the author notes in the book, but so is history). Then she began bringing scores of traveling vaudeville acts to Richmond, though she clearly did so out of economic self-interest, not any egalitarian principles, Wong says.

Not only was Thorp one of few women to contribute to the early growth of film popularity in this country, but by providing Richmond’s Black audiences with access to traveling Black performers, she inadvertently contributed to the success of Black vaudeville in the Jim Crow South, a subject that Wong believes has not received the scholarly attention it deserves.

Consistently defying ingrained gender constraints, Thorp was the original animating force behind the book. But in the end, the Black vaudeville angle became Wong’s favorite aspect of what she learned while researching the book, which she notes was peer-reviewed before publication this year by The University of Tennessee Press.

“Because it’s history that is unknown or lost,” she explains. “Plus it affected people who had no other outlet. The performers who came in were bringing in fashions and ideas from all over the country that African-Americans at the time just did not have access to. For it just to be forgotten or not mentioned in books on theater here in Richmond, I think is just incredible.”

-

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Raines

- This photo can be dated circa 1928-1930 due to the presence of the Liberty Meat Market to the left of 18 W. Broad St.

Richmond’s movie pioneer

Having visited once and seen the ‘ka-ching’ potential on a busy Broad Street humming with people, Thorp left behind a shiftless husband in Bucyrus, Ohio and moved to Richmond to start her movie empire. She already had experience showing films in the Midwest, but this was “her first real theater,” Wong says, defined at the time as having seats that were bolted down, unlike the outdoor tent shows then operating in Richmond, which typically involved a big white sheet and an unruly crowd.

The author notes that once Thorp switched the Dixie to all-Black patronage, which included improving health and safety measures in the theater, there were hundreds, maybe thousands of performances, and tens of thousands of Black patrons who walked through the doors. Remember this was during a time when theater was mostly an activity for “white elites.”

“The more I looked at Black vaudeville, the more I realized it wasn’t for the elite African-American patrons at all, which was what was so unusual and so cool about it. There was no radio or TV back then, African-Americans seldom got a chance to see a live performance, especially of African-Americans, but if they did it was down at Theater Row, and then only from up in the galleries, once in awhile, when invited.”

So why is there so little information about Black vaudeville in Richmond? Wong offers several reasons. “Of course, the white press at the time wouldn’t cover it, and [Black journalist] John Mitchell [of The Richmond Planet] was more interested in politics. He rarely published anything on entertainment. But there was a newspaper in Indianapolis, Indiana, of all places, which was acting as a trade publication for vaudeville players. They covered this early circuit [which included Richmond].”

Because she was a rarity in the industry, Thorp was often covered by the movie exhibitor trade magazines of the period, which became a treasure trove for Wong during her extensive archival research.

-

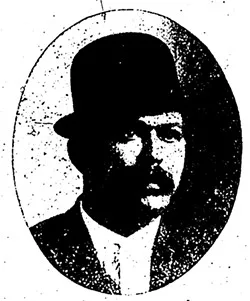

Photo courtesy of the author

- Charles Moseley, the African-American entrepreneur who also started early Black theaters in Richmond. Image is from the Dec. 23, 1911, Indianapolis Freeman, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Also while writing the book, Wong learned about the occasional Black entrepreneur or promoter of the early 20th century, such as Charles Moseley from Atlanta, who used to bring acts to a former skating rink near First and Charity streets starting in 1908. But by and large, most of the owners were white men, she says. “I don’t think African Americans could succeed in running their own Black theaters because they didn’t have the resources,” not to mention the exhibitor organizations, or trade groups, were exclusively run by whites. Though Thorp didn’t get too involved in Richmond society when she lived here, “she was able to be accepted as a peer among the white men in the theater industry,” Wong says, which may surprise some readers. Others, not so much.

Thorp did not come from wealth, but was a savvy businesswoman and her marketing skills were “unbelievable,” Wong says. “I think she learned from everything she did and built upon each endeavor … it was certainly impressive for a woman at the time, and she was 45 when she came to Richmond.”

In fact, the Dixie did so well that Thorp was able to buy a lot in Jackson Ward, where she would open the famous Hippodrome Theater in March 1913, solely for the purposes of Black entertainment; a renovated version of which still operates today. Wong says she was surprised to learn that few people today know that Thorp built that theater, where she began by charging three different admission prices: 10 cents, or roughly $3 in today’s dollars, 20 cents and 30 cents.

You’re gonna need a bigger book

Kathi Clark Wong grew up around the newspaper business in Arkansas. Her father had weekly newspapers and she would later work for The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette for several years before a career as “a political analyst,” as well as teaching Spanish at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville for eight years. She’s always been interested in history since her undergraduate days in Arkansas in the 1970s.

Since moving to Richmond six years ago, she has been pleasantly amazed by the area’s history. “It’s true it’s not just in one area, it’s in every possible area of American history,” she says. “And you have such wonderful resources right here.” For her, a big bonus while researching her first book was “everything being online” and the presence of more digitized newspapers.

Wong learned during her research into Black vaudeville about a level of subversive entertainment happening onstage, especially when traveling Black minstrels performed in Richmond. She encountered the disturbing fact that some Black performers actually performed in blackface, a popular form of the times (rightly condemned today), for Black audiences. “But they were taking those stereotypes and turning them inside out and taking ownership of them,” she explains. “I think that’s another reason why there’s not a lot written about Black vaudeville – because of all the uncomfortable words [and imagery] associated with them.” She agrees these early performers were using art in a similar vein to Black hip-hop artists a century later, who often reclaim racist language in their songs, some of which become Top 40 hits.

Another interesting historical aspect within the book is that Thorp’s busiest time in Richmond came during the Great Influenza epidemic of 1918-1919, which of course affected the theater industry. The author says she “100%” saw interesting, familiar connections with the COVID-19 pandemic that came roughly a century lately. “It was just so fascinating, all the same controversies, everything. Just how quickly it spread,” she says. She writes in her book that one way the 1918 flu pandemic spread was through former World War I soldiers coming back from Europe to Petersburg, then going out to Richmond to enjoy the nightlife.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Thorp eventually moved away from entertaining Black audiences and started other movie theaters for white audiences in Richmond. As the author says: “Thorp never mentioned [Black vaudeville] in retrospective interviews that she did later in life, and I think it’s because she didn’t value it.”

Lately, Wong has been busy putting more information together as well as a timeline of Black theaters for possible future work; she may feel compelled to write another book, she says. She currently has a 39-page working document of Black performances in Richmond that she compiled from the years of 1908 through 1962.

As for Thorp, she would die in 1926, just before movies with sound, or “talkies,” began to take off. But one of her protégés, Walter Coulter, who worked with her in Ohio and then followed her to Richmond, where he was a loyal employee for two decades, kept on showing movies in Richmond. In fact, he would build a majestic gem of a theater with partner Charles Somma that you may have heard about, the Byrd Theatre, which audiences of all races still enjoy today.

Continue reading a piece below by the author about what she learned.

Upcoming appearances for Kathi Clark Wong include a lecture for Osher members at University of Richmond on Sept. 28 and the Common Ground Book Group at Library of Virginia on Nov. 14 at 6 p.m.

-

Photo courtesy of the author

- The cover of Kathi Clark Wong’s book, “Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp” (The University of Tennessee Press, 2023),

In Her Own Words

The author of “Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville” looks back at what she discovered about Black Vaudeville in Richmond.

Editor’s note: Before an interview with Style Weekly, author Kathi Clark Wong sent the following article summarizing some of what she learned while writing her recently published book, “Nickelodeons and Black Vaudeville: The Forgotten Story of Amanda Thorp (The University of Tennessee Press, 2023). After reading her book, I ended up conducting a long interview with her, but it’s worth reading her more detailed piece below to get a sense of her writing style – and to learn more about the history of some well known Black entertainment venues in Richmond.

In March 1910, Perry Bradford appeared at the Dixie Theater at 18 West Broad in Richmond and sang “When Jack Johnson Wins the Championship of the World.” In so doing, said an African-American newspaper out of Indiana, he “set (Black) Richmond wild.”

Bradford was among the first of several hundred African-American vaudevillians to perform at the Dixie in the early 1900s, among them some of the finest acts touring the country at the time. The Dixie predated by only a couple of years the much more well-known Richmond Hippodrome, which itself also hosted hundreds of early Black vaudeville acts.

Vaudeville is sometimes thought of as merely silly entertainment, with people spinning plates at the top of poles or showing off a trained chicken that pecks out a tune on a piano. According to David Monod, author of “Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925,” however, “there was much less slapstick and nonsense in vaudeville than we generally imagine.” The Dixie and the Hippodrome, along with a handful of giant tent shows and other, smaller all-Black venues that popped up in and around Jackson Ward provided Black entertainment in the form of vaudeville to the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of Black patrons. This was at a time when African-American access to public entertainment was most often relegated to segregated galleries of white theaters – if and when even that was allowed.

Black theaters, however, provided a different experience for Black theatergoers. A few months after Bradford’s Richmond performance, the same newspaper noted, “You can enjoy yourself better (in a Black theater) because the average performer can say things . . . that place him three times funnier than he would be at a white (amusement) house, and of course he opens his heart to us because he is among his own people.” Songs were the most popular acts in vaudeville, and Bradford’s – about a Black man winning the world heavyweight title against a white fighter – appears to have been openly transgressive with an almost literal message of class struggle.

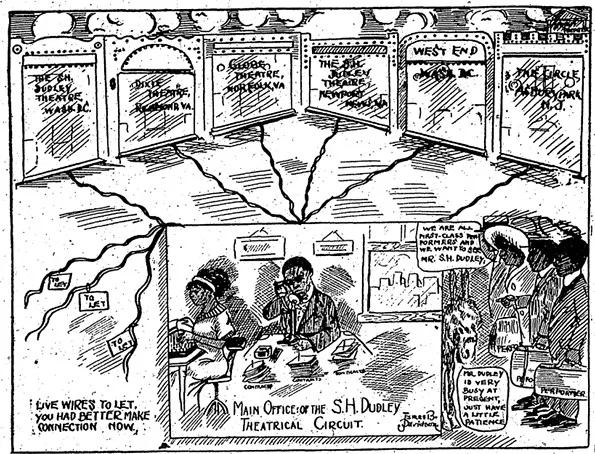

-

Courtesy of the author

- The Dixie Theater was one of the earliest on the African American Dudley Circuit. It was critical to the circuit’s success because of Richmond’s hub-like location enabling vaudevillians to travel to and from several other cities in the Southeast. Drawing is from the August 24, 1912, Indianapolis Freeman, Indianapolis, Indiana.

The Dixie Theater

The Dixie may not have been the first Richmond venue for African-American entertainment on a larger scale. A Black man out of Atlanta named Charles Moseley had been bringing in some acts to a former skating rink near First and Charity streets since about 1908, and a few acts had also cycled through the Ideal Theater, a short-lived store-front venue opened by persons of unknown race near today’s VCU’s Institute for Public Art. But the Dixie was groundbreaking in its success and longevity as well as the particulars of its unusual foundational story that includes the story of the Hippodrome.

Charging five cents a throw, the Dixie Theater was established in May 1908 as a nickelodeon showing the silent films that were all the rage in the early 1900s. Amanda E. Thorp, 45, a white woman recently out of Ohio, had started the theater as a venue for white patrons only in segregated Richmond. Early on, she realized that because of the theater’s proximity to the predominantly Black community of Jackson Ward, she could make more money by converting the venue to an African-American showplace (it is duly noted that Thorp’s ownership as a white woman makes the nomenclature of the Dixie as a “Black theater” problematic). She continued to show films in her now all-Black venue for a while — films by white producers with white actors narrating short vignettes of white experiences, the only moving pictures that existed. It was not uncommon, however, for nickelodeon operators to supplement their film offerings with vaudeville performances, and Thorp, who understood her market, began to bring in a few African-American acts to intersperse with her pictures. There is no doubt that these acts were well-received; Thorp would have quickly realized that she could provide Black Richmonders an entertainment experience that no one else in Richmond was offering – and she could make money doing it.

Thorp was an entrepreneur at a time when few women were entrepreneurs. Even so, the evolution of the Dixie to an all-Black vaudeville venue was a bit of a detour for Thorp’s overall career trajectory, and she moved on to developing other (white) movie theaters in her adopted city of Richmond. Managing her various projects was too much for one person, and sometime before 1912 she brought Walter Coulter to Virginia from Bucyrus, Ohio, to help.

Coulter, about 22 at the time, had been in Thorp’s employ in the little nickelodeon she had previously owned in Bucyrus. Thorp put Coulter in charge of the 100-seat Dixie, and it was likely Coulter who managed the considerable amount of legwork involved in engaging the multiple (Black) acts the Dixie brought to Richmond, a task made more complex by the twice-a-week changes of performances at the theater. It would have been a relief to Coulter in early 1912 to contract with the newly created Dudley Circuit out of Washington, D.C., to provide the number and variety of African-American vaudeville acts that the Dixie needed. The Dixie was one of about ten or so theaters throughout the Eastern United States – and the only one in Richmond – that were members of the Dudley Circuit in the early days, all of them Black-patronized and all, except for the Dixie, Black-owned and Black-managed. Thorp continued to develop her white venues, but the success the Dixie was having under Coulter’s management did not escape her attention. In July 1912, she capitalized on it by buying a lot in the heart of Jackson Ward where she would build a bigger theater for bringing in Black vaudeville. That theater would be the Hippodrome, the first theater in Richmond built expressly for the purpose of hosting African Americans to see Black entertainment.

The Hippodrome

The Hippodrome, today Richmond’s most affectionately remembered Black theater, opened in March 1913 promising two performances each evening, Monday through Saturday, consisting of “four big acts” at admission prices of 10, 20, and 30 cents. By then, the Dixie had expanded to seat 250 customers and had hosted more than 50 Black vaudeville acts. After the 700-seat Hippodrome opened, Coulter found himself for a brief time managing both it and the Dixie. The Dixie continued to host Black vaudeville acts – another 50 or so at least – until Thorp sold it to Charles Somma in early 1915. Somma, also white, was a Richmond native who had gotten his start in the ice cream business with his father in a shop located not far from Thorp’s Rex Theater. Thorp sold the Hippodrome, also to Somma, in May 1916, after it had brought another some 250 Black vaudeville acts to Richmond. Somma continued to bring African-American vaudeville acts to the Dixie and the Hippodrome for several years, but converted the Hippodrome to a movie theater (still for African-American patrons) in the early 1920s.

Eventually, he sold both properties in order to move on to other ventures, notably with Coulter, including the development of the Byrd Theater. The Hippodrome that Thorp built in 1913 was destroyed by fire in 1945 and was rebuilt shortly afterward as the one still standing in Jackson Ward today. It is not known when the Dixie closed, but perhaps not long after Somma took over the Hippodrome; the building housed a woman’s clothing store by May 1921.

“Mr. Bojangles” and other stars

Richmonders are well acquainted with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the talented local entertainer who made it big on the national stage, having moved to New York where he got his start in the vaudeville theaters there. The rich presence of Black vaudeville performance in Richmond itself, however, is largely unknown. One reason for this is that the acts in Richmond generally were not covered in the local press, not even in the African-American Richmond Planet, which instead concerned itself with reporting about matters which the publisher likely thought were of more overt political import to its Black readership. It was the Indianapolis Freeman in Indiana, of all places, that covered early 1900s African-American theater news across the country. The Freeman reported in great detail and provided in hundreds of articles the names and characterizations of acts which appeared at the Dixie and the Hippodrome as well as other theaters inside and outside of the great theater cities of New York and Chicago.

Many of the African American vaudeville players who came to Richmond in the early 1900s went on to have successful careers not only in Black theatrical circles but also by crossing the color line and becoming well-known stars in both film and television as those genres evolved. Perry Bradford was a popular songwriter and manager of the careers of other well-known African entertainers. He is best known today for his important contributions in developing the blues genre.