This feature is part of ART & ABOLITION, a series examining art as a tool for reimagining alternatives to incarceration and as a means of rehabilitation for systems-impacted individuals.

Artmaking has always been a crucial tool in dismantling oppressive systems. Consider the myriad public and private installations, protest anthems, and written stories produced in response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Mahsa Jina Amini, whose only crimes were being Black, female, or both. Painter Russell Craig, conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas, and writer Brea Baker have uniquely harnessed the power of art to interrogate America’s legal justice system specifically, creating work that not only critiques the prison-industrial complex at large but also awakens audiences to the dehumanizing realities of life inside and the power of art as an avenue toward freedom.

For Craig, who himself was incarcerated for over a decade, artmaking has played a monumental role in allowing him to reclaim his agency, generate income, and help other similarly affected community members. His practice largely centers on portraiture of systems-impacted individuals and large-scale works painted on pieces of leather—derived from purses, clothing, and the like—to represent the Black body in America. In 2017, Craig co-founded the Right of Return USA with fellow formerly incarcerated artist Jesse Krimes, launching the first national fellowship initiative focused on supporting formerly incarcerated creatives. An alum of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s restorative justice program, Craig has now partnered with the nonprofit as a muralist, painting large-scale works addressing the carceral system in under-resourced communities and teaching art to court-involved youth.

More From Harper’s BAZAAR

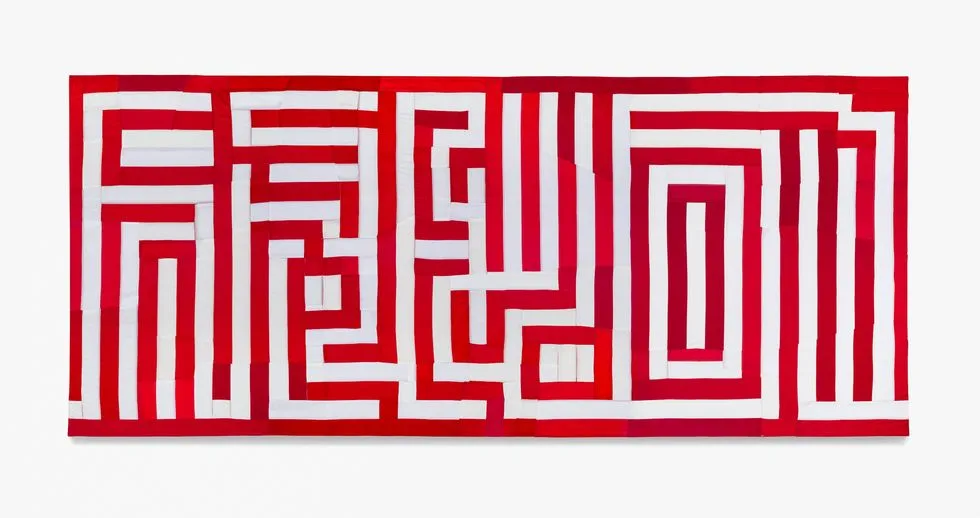

Thomas works across sculpture, painting, photography, screen printing, and mixed media, exploring themes of race, identity, politics, pop culture, and the commodification of the Black body in America. Aiming to expose how a system of modern-day slavery still exists in this country, he crafts large-scale fabric sculptures from American flags and prison uniforms, stitching them into mazelike motifs with phrases like “We the People” and “Land of the Free” that directly challenge the current economy of incarceration. Ahead of the 2016 presidential election, Thomas co-founded the artist collective For Freedoms, which helps center artists’ voices in conversations surrounding politics and encourages creative civic engagement as a means of galvanizing radical change.

As chief equity officer at social impact firm Inspire Justice, Baker similarly advises creatives on how to leverage their platforms and artistry in service of social change. A prolific writer, she covers race, gender, and sexuality for publications including Bazaar, and is working on her debut book, Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft & The Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership, which will examine how land has been systematically stolen from Black families in the United States.

Recently, Craig, Thomas, and Baker connected to discuss the importance of politically motivated art, whom they create for, and the dangerous ways the opposition is furthering racist narratives through media.

Brea Baker: I really do believe that, in general, artists are the gatekeepers of truth. That is a Harry Belafonte quote that I love and live by. I believe that writers, specifically, can open up political imagination and possibilities. Writers help us step outside of the box to learn historical context, but also to remember that we get to spark new possibilities for ourselves. I follow in the tradition of Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison, who used fiction in those ways, but also nonfiction writers like Isabel Wilkerson who really want to make the past plain, so that we can move forward in an honest and integrity-filled way.

I started my writing work writing articles around police brutality, centering families who have lost loved ones to police violence, and reimagining a world without police, incarceration, and those sort of chains—metaphorical and otherwise—that hold people back from the opportunity and freedom that we really all do deserve access to.

Russell Craig: As y’all all know, I’m formerly incarcerated. I did a total of 12 years in prison. But I was always an artist. When I was in prison, I met Hank, and I let him know that he was very inspirational to my work. I used to do a lot of representational things like portraits, but I started to think more conceptually after observing Hank’s work when I was inside.

As far as my art practice now, there’s a lot of stuff that we all know about prison, but I try to bring personal things that happened to me into my work to enlighten people. On the other side, I like to give hope to anybody that’s in prison that they can get out and change things. There’s not enough change happening, but I don’t want to give up.

Hank Willis Thomas: Thank you, Russell, for reminding me of the fact that my work was speaking to you when you were incarcerated. Did we meet in 2015 or 2016?

RC: It was in ’15 at the Democratic National Convention.

HWT: Yeah, exactly. Before I met you, I saw your work and felt like you were really bringing an intimate personal perspective to all of the institutional language and the dehumanization that you experienced, both while you were inside and in rebuilding or creating your life afterwards.

A lot of my work has always been inspired by the quest for freedom through, during, and after slavery in the United States. As I became more and more aware that we are still living in a slave state, I felt that it wasn’t enough for me just to talk about the past and that I should, in my creative practice in various ways, talk about the ways in which our criminal legal system, criminal injustice system, our society in general actually doesn’t live up to its highest standards, and probably doesn’t live up to its lowest standards. In my work, I use prison uniforms to create texts with mazes that say things like “freedom” and “liberty” and “equality.” I also collaborated with Dr. Baz Dreisinger and students from the Prison-to-College Pipeline program at Otisville state prison and made an installation called “The Writing on the Wall,” which has taken various forms. These installations are made up of all of these different writings that Baz has collected through her work around mass incarceration and its proliferation all around the world, and they invite viewers to read the words of people who are currently or were formerly incarcerated.

Russell, you and Jesse [Krimes] have really been on a mission for the past almost 10 years, and it’s really been amazing to see you grow as people but also as artists. I’d love for you to talk a lot about the various issues that you are confronting not just about prison, but also about identity, masculinity, and power through your work.

RC: Absolutely. Even before I started attacking prison issues, I wanted to be an activist for Black struggle outside of prison. But then I revisited my prison experience—there’s still trauma there—and I came up with a way for how to not dwell on the past, because a lot of people didn’t make it. Even if their body physically makes it out of prison, their mind gets lost.

It’s a little disturbing to realize that a lot of people don’t see what I’m seeing. I thought everybody knows what is going on [within the prison system], but they really don’t. On top of that, there are other components of white supremacy and white oppression that keep evolving. Like in the movies, for example. I read Marvel comics while I was a kid—all of them. So, I know all about the storylines. In the comics, Kang the Conqueror was never Black; but now in the Marvel movies, he’s a Black man—and he’s evil. What they’re doing is programming people, young Black people, that we’re nothing but negative. Every time they see a Black celebrity, he’s negative; he’s a negative rapper with all his money who is just all about himself.

My work has evolved since I first started; I’ve gotten more conceptual. Part of me is proud that I had to elevate, because when things are too in-your-face, people get used to it and become accustomed to oppression. The goal is to try to stay in the game and wake up one person that’s in our situation or wake up one white person that has some power that can talk to another white person that can help stop all this oppression or calm it down. White supremacy is all over the place, and prison is just one component of it. So that’s what I talk about in my work. It’s starting to become more abstract, but the conversation is still the same.

BB: I’m writing a book about reparations and land theft. In this country, Black people were the exclusive workers of the land, the forced workers of the land, and now, this country is happy to have Black people working the land but never owning it. You now have a bunch of young people who don’t want anything to do with anything agricultural because they associate it with slavery, even though there is so much magic and healing and redemption in being out in nature.

I’m curious for both of y’all, in your creative practice, who you feel your target audience is? Do you feel like you’re talking to white people and/or people in positions of power who can un-divest from white supremacy? Or do you feel like you’re talking to other Black people? Or do you think both? That’s something that I’ve struggled with in my creative practice; I start off writing something for other Black people and then feel like, How do I make this make sense if a white person reads this and I want them to unlearn and change their family’s minds and whatnot? But I also don’t want to cater to that gaze.

RC: I’m definitely struggling with that. I’m in a predicament where my work is being directed towards a specific audience, which is white and wealthy. When I started, I wanted to wake up my people to what was happening in the U.S. But I’ve been learning that they don’t want to hear it; they’re so conditioned. That’s how damaging the control over movies and music is; things will get so embedded in people.

The only people that are really listening and buying my work are rich white folks, and they’re so privileged that they don’t understand what I’m thinking. But as artists, it’s our job to bring [these topics] to them. It doesn’t always have to be super heavy, and that’s why the work has to be smart. I’m a hood cat, so I had to learn how to elevate to be able to be understood.

I applied for a creative capital grant, and I’ve made it to the second round. I want to use the money to travel around to places like Atlanta and expose our people to conversations like this one. A lot of the time, the people who I want to get these messages to don’t even see the art that I do. They don’t go to museums. I’m starting to be in a situation where they look at me as bougie or like I’m unrelatable. That creates a disconnect, and then it’s hard to get the message to who the message was intended for.

People coming from my experience—from prison, poverty, the hood—there are a lot of things in their way, but they still need to have the belief in themselves that they can overcome things. That’s the kind of stuff I’m trying to put into my work.

HWT: I disagree with that, actually. Do you know how many people have seen your work? I’ve seen your work in newspapers, I’ve seen it in museums, I’ve seen it in local community galleries, I’ve seen it in pop-up spaces. Every time one of us gets through the door, our job is to keep the door open for other people. You’ve done that and continue to do that.

A lot of my work is about emancipation, and I’m constantly challenged by my own notion of who I am and who I can be and what I can be. What I appreciate [about] everyone here is that we recognize that our responsibility is to constantly be in a process of self-awakening and to wake other people up.

My audience is anybody who’s breathing and wants to keep breathing. I feel like we are all oppressed by the systems that put us in these forms of peril, and there are a lot of people who are rich and who are not and have never been and will never be incarcerated that aren’t free. Some people think that they’re on the outside and living a good life, but they’re actually so confined and they’re so impacted because of things like the pharmaceutical industry, social media, and entertainment.

But I also feel like optimism is also a critical thing in the world—we make our work because we have hope. If you are cynical in the way that I tend to be, you can lose sight of the real blessing, which is that every moment that we have to breathe not only involves us but anyone who’s in our presence.

BB: Hank, something you said is really sticking with me, which is that your audience is anyone who’s still breathing and wants to keep breathing—we all suffer from our current criminal legal system.

I’ve been noticing this trend across new documentaries and movies that have been coming out on Netflix, where [there’s an implication that] if the police were not part of the stories, they would’ve ended so differently. Anytime you turn on a movie now, the head director of the FBI is a Black woman. All of the cops, all of the CIA detectives are suddenly Black people who were able to move up in the ranks in the pursuit of justice.

It’s mind-blowing to see this happening after 2020, after “defund the police.” I thought we all got on the same page and realized this is propaganda in action. That is something that has really been sticking with me, as far as how the opposition is using the power of art. It’s not just progressives and abolitionists who are trying to open up minds; the opposition is also trying to cement a narrative around the police that says there is no safety without them, there is no safety without prisons.

Russell, you’ve mentioned trying to be a bit more abstract and conceptualizing in different ways and not being so on-the-nose. In my writing work, I’ve felt the need to do so much myth-busting and fact-checking and providing an arsenal for people who want something different but are constantly being bombarded with propaganda that says something different is not possible.

I keep bringing up Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison because I love what they’ve been able to do with fiction. I’ve currently found myself in this place of, as a writer, feeling the need to be part of the pushback against the propaganda machine by being more straightforward with my work, but then wanting to trust the audience more and allow them to answer questions and ask those questions of each other.

HWT: I think different people have strengths in different areas. It’s not just right and wrong or good and bad. It’s such a multilayered, complex system that it’s almost impossible for anyone to address everything all at once or even to hear it and face it all at once, because at the end of the day, we are all part of the problems we’re attempting to address, and we’ve been conditioned to be that. To actually live in a free society, we need to envision it; we need to challenge the society that we have. We also need to look in the mirror and be as humane with ourselves as we should be with others. I don’t know about you all, but I know that I’m not as kind and good to myself as I deserve to be.

My goal is to be an old, free, happy Black man. However, destiny is already written, to a degree. I think about artists like Bob Marley who died at a relatively young age, but he is as alive or more alive now than he was as a terrestrial being.

If I can paint to something that feels true to me at my core, it’s not always going to be everything I say. But as long as I can say things that I feel like are going to be in that infinite timeframe, I feel like I’m free. That’s the goal for me, to be free—not to serve a progressive or a conservative agenda, because that’s all another way of imprisonment, putting myself in a box. I evolve and continue to evolve. I go back to things that I didn’t agree with before. I feel like that is my responsibility as an organic being, and the fact that some kind of crazy people during the French Revolution came up with these left-wing, right-wing binaries while they were literally killing each other—I don’t want to be involved in that.