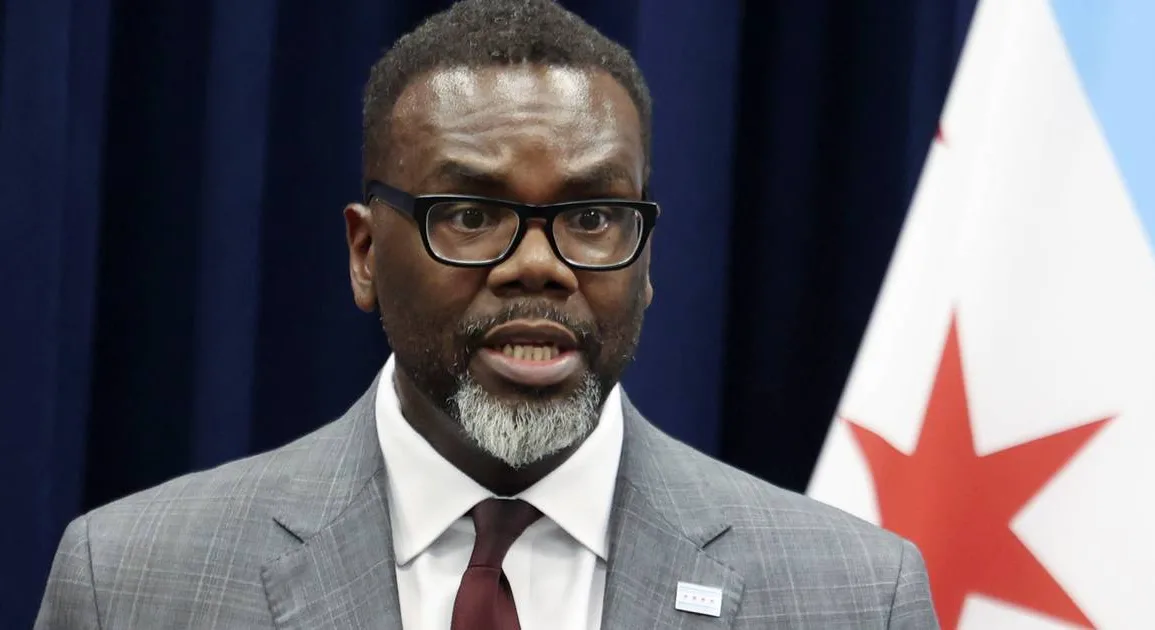

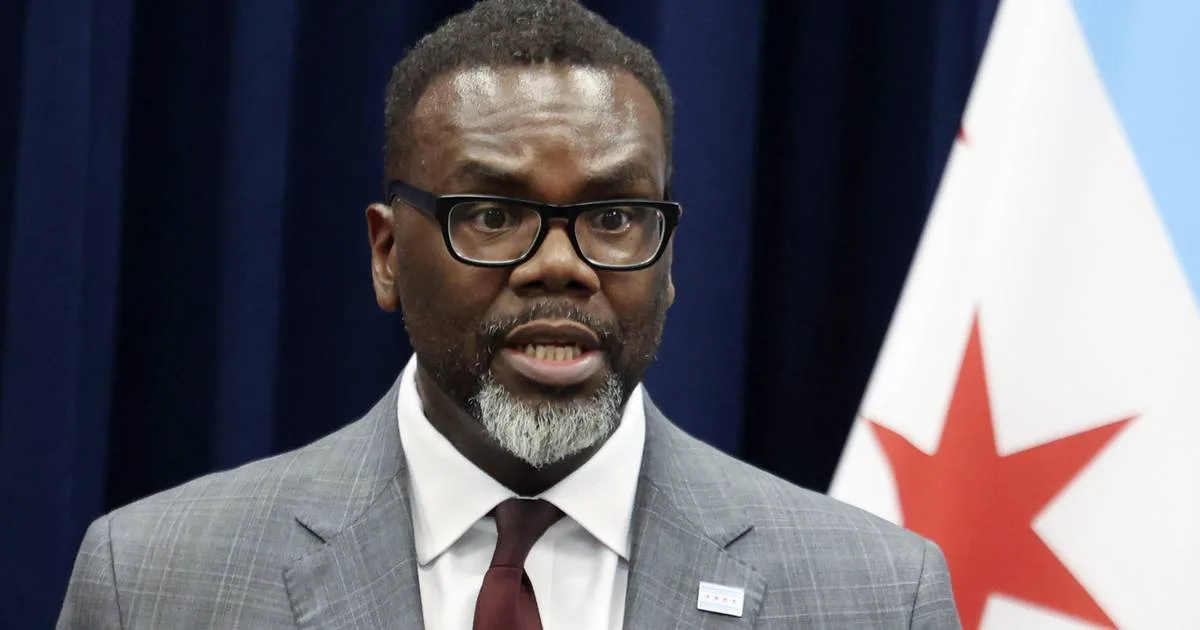

After weeks of turbulence at City Hall, Mayor Brandon Johnson is asking aldermen Wednesday to approve his first budget, a proposal saddled with new costs for both next year and the future, compared with when it was introduced last month, but also larded with sweeteners to smooth the pathway for a yes vote.

Among those new costs are a pension fix estimated to cost more than $60 million, a new office dedicated to helping people returning from jail or prison, and funding for 50 new ward staffers — one for each alderman.

The biggest of the additional expenditures are for the Chicago Police Department. Already one of the city’s largest outlays, CPD expenses are expected to grow thanks to a new proposed contract and the passage of recent pension legislation in Springfield codifying certain retirement benefits.

Last month, the city and the union representing rank-and-file police officers reached a tentative agreement on a new four-year contract that would provide a roughly 20% raise. Officers and detectives would receive a 5% pay hike in both 2024 and 2025, and cost-of-living raises in the two years following. Active-duty officers in the Fraternal Order of Police would also receive a one-time $2,500 retention bonus.

Based on current active employee counts, budget officials expect the extra cost in 2024 to be approximately $64 million, though a final number won’t be known until early next year. While the contract agreement was announced in late October, city finance spokesman Jeffrey Garceau said the contract’s cost was already built into Johnson’s budget proposal. The City Council must still approve that contract.

But the pension change to bring Chicago police benefits in line with recently boosted firefighter benefits is a new expense. It removes a birth date restriction that limited annual cost of living adjustments for pension benefits.

After the firefighters’ fix added $6 million in normal annual costs for its pension fund and boosted long-term liabilities by $196.5 million, the watchdog group the Civic Federation warned the impact of a similar tweak for police would be even steeper. That echoed warnings from Johnson’s predecessor, Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who said the change would cost as much as $90 million more annually.

Despite those warnings, Johnson endorsed the change.

And the cost will be hefty — to the tune of roughly $60 million — but will not hit until Johnson’s 2025 budget, according to Garceau, because of the timing of the legislation’s passing.

Johnson’s 2024 budget is very likely to pass. He enjoys solid support from a large bloc of aldermen, and the spending plan includes no new property tax increase.

Nonetheless, he’s following the mayoral tradition of adding sweeteners to annual budgets to win over hesitant members of the City Council. While many are meant to be one-time infusions, Johnson administration officials also agreed to set aside millions to allow each alderman to hire one more full-time ward staffer.

Johnson heeded the frequent complaint from aldermen that they need more help, and a budget amendment cleared committee last week including a wage allowance for council members to now hire four full-time salaried employees at an estimated cost of slightly under $5 million.

Johnson proposes paying for the extra staff by eliminating a past year’s budget sweetener: $100,000-per-alderman “microgrants” to be spent on ward services.

That additional staff comes on top of recent raises the vast majority of City Council members accepted this year.

Johnson also announced last week that he was launching a new office of reentry — under the mayor’s office — to support formerly incarcerated Chicagoans.

It was an early demand of Johnson’s vice mayor, Ald. Walter Burnett, 27th, who worried the 13 new positions created to address Chicago’s migrant were coming at the expense of those working to help residents returning from prison or jail. Four positions were budgeted in the office at a cost of roughly $430,000, paid for with funds from the city’s cannabis tax fund.

Overall, the office’s budget will be $5 million, the mayor’s office said, and includes money to provide grants to outside organizations, with a goal of ensuring formerly incarcerated individuals have access to jobs and resources.

“Only in this administration is this investment being made,” Johnson told reporters last week, flanked by several members of the Aldermanic Black Caucus. “When I said we could take care of everyone in Chicago, I mean it.”

He also announced funding for a new $500,000 commission to study potential restoration and reparations to descendants of enslaved people. After years of fits and starts to support a special City Council subcommittee on the issue, “these are the first dollars spent in this city to actually begin the process of studying both restoration and reparations,” he said.

Johnson’s budget counts on $90 million in savings from bond refinancing. Of that, $19 million is coming from savings from a transaction completed in the spring.

City officials have reassured outside watchdog groups like the Civic Federation that the refinancing will not be a return to the city’s problematic “scoop and toss” practices: paying off old bonds with proceeds from new ones. Such maneuvers can provide savings in the short term, but depending on the structure, can extend the timeline for paying back the debt and increase the total cost of debt. That’s not the case this time, city officials have said.

Those savings will come from a refunding transaction that combines general obligation and sales tax securitization bonds, Chief Financial Officer Jill Jaworski said last month. Given how high current interest rates are, “we won’t get as much savings as when interest rates were 2%,” she said, but the expectation is “we will still generate significant savings.”

Those savings won’t be clear until the next planned transaction, which would not come until the final quarter of 2024.

The structure of that refinancing hasn’t been decided yet, but the due date for paying back the debt will remain the same. Though savings from refinancing are generally spread out over future years, the city plans to budget those savings upfront.

Johnson’s administration, like Lightfoot’s before it, is counting on an increase in reimbursements for ambulance runs to help plug the 2024 budget hole.

The city is estimating it will collect $62 million more in charges for services for Ground Emergency Medical Transportation. That sum is a reimbursement from the federal Centers for Medicaid Services that gets passed through the state.

That reimbursement is booked with other public safety charges for services, but the bulk are ambulance reimbursements, budget officials say.

Despite skepticism that the feds would deliver, those public safety charge revenues jumped from $80.2 million in 2019 to $266.5 million in 2020 and have outperformed projections since, according to budget documents.

The city budgeted to collect $315.5 million this year, but is on track to bring in $377.6 million before the books close at the end of December, according to Johnson’s 2024 budget proposal. His administration budgeted to collect that same $377.6 million in 2024 — $62.1 million higher than last year.

Contrary to worries from downtown aldermen, Johnson’s TIF surplus does not endanger a revamp of LaSalle Street first pitched by Lightfoot, budget officials say.

In all, Johnson plans to declare a record $433.8 million surplus from the special taxing districts in 2024, giving the city’s corporate fund a $100 million boost.

Of that total, $95.7 million would come from the district covering much of LaSalle Street in the Loop, and the rest would come from 29 other districts around the city.

Downtown aldermen Bill Conway, 34th, and Brendan Reilly, 42nd, both took issue with the surplus plans for the LaSalle Central TIF, fearing it would endanger a slew of pending projects to revamp the city’s main financial drag.

Lightfoot’s LaSalle Reimagined initiative aimed to use TIF dollars to convert some of LaSalle’s 5 million square feet of vacant space into residential and retail use. In all, five projects were selected from an initial applicant pool of nine. Those five are still under consideration for funding by city officials.

During planning department hearings, Conway fretted that the TIF fund was being “drained,” while Reilly worried continued budget pressures would erase the pot of money developers are counting on.

But internal TIF planning documents provided to the Tribune back up Johnson officials’ contention that the projects wouldn’t be harmed: The city budgeted for a total of $320 million for those projects in 2025 and 2026, when some of those renovation projects along LaSalle could break ground. If planning officials opt to go ahead, the LaSalle Reimagined proposals would still need to be confirmed by the city’s Community Development Commission and the City Council.

After declaring the surplus, the balance for 2023 would be about $78 million. And with other district obligations for 2024, the balance will drop to $6 million.

Annual hefty collections will largely replenish the pot: Even if it were drained entirely this year, the TIF is expected to rake in somewhere between $170 million and $200 million in diverted property tax revenues every year going forward.

LaSalle Central has been one of the city’s best-funded TIFs, ending 2022 with a balance of $226 million.