For decades, Black barbershops have been recognized by scientists and policymakers as powerful hubs for delivering health information in ways that change behavior. Since 1970, at least 512 studies in the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database have examined how these shops have been used to influence Black men’s awareness of health issues ranging from hypertension and HIV prevention to cancer screening and diabetes management. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government partnered with 1,000 Black-owned barbershops and hair salons nationwide to provide trusted information on vaccination, testing, and misinformation about the virus.

“Gap in the Literature”

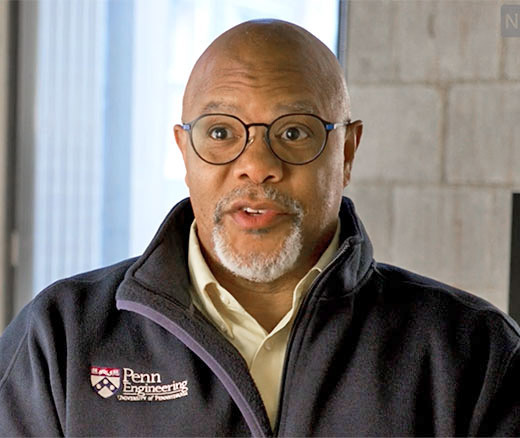

However, in a new study done in collaboration with a team at the University of South Carolina and published in Oxford’s Translational Behavioral Medicine, LDI Senior Fellow and Penn PIK University Professor Derek M. Griffith, PhD, notes that while the world knows how effective these programs can be, it doesn’t exactly understand what factors make a Black barbershop health care intervention a success or failure. Hard data on that question remains “a gap in the literature,” he writes.

Griffith is a Professor of both Family and Community Health at Penn’s School of Nursing and Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the Perelman School of Medicine.

Although the Black barbershop concept has been universally lauded, some of the programs have failed—apparently because of lack of funding, volunteers, or space constraints. Others have not been optimally effective for reasons speculated to be lack of trust, privacy concerns, confidentiality issues, limited scope, unwelcoming atmosphere, patron reluctance, or cultural insensitivity.

Novel “Implementation Premortem” Method

To get a better sense of the exact factors driving success and failures, the research team conducted an “implementation premortem” investigation. Unlike a postmortem, which analyzes a project’s failure after it occurs, an implementation premortem is a proactive exercise conducted before a project’s launch. This strategy helps anticipate and mitigate potential risks during the design phase. Experts assume an imagined project has failed and work backward to identify the causes. This approach often reveals hidden risks or blind spots and allows teams to adjust before finalizing and launching the project.

Black Male Participants

The team recruited a panel of 23 Black males with an average age of 40 years. In focus groups, the participants were provided a generic explanation of a theoretical Black barbershop health program that failed. Though given few details, they were asked to brainstorm and individually identify the most likely reasons for that failure and suggest solutions more likely to achieve success. Then, they engaged in a group discussion focused on the reasons for failure they cited.

The participants’ responses were processed into an Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework tool that analyzes the various stages and influences involved in matching the information points to real-world settings and behaviors.

The Results

The results were that the primary reasons for program failure were that the program may have conflicted with men’s work schedules, childcare and other family obligations, or been at a location that was too distant or difficult to access. Any one of these would have made for a poor program fit during the implementation.

Other major concerns identified by participants as being elements of the potential success or failure of a program were:

• Economic challenges (cost of health behaviors like therapy and nutrition).

• Community ownership and engagement.

• Staffing and cultural sensitivity (importance of facilitators who resonate with participants).

• Trust and transparency in researcher intentions.

Recommendations

The researchers recommended:

• Ensuring flexible and accessible program scheduling aligning with work and family obligations.

• Using community-driven messaging to build trust and demonstrate the trustworthiness of the researchers.

• Engaging community leaders and barbers in the intervention to optimally align the approach with the local context and values.

• Providing economic incentives and reducing financial barriers.

“In the future,” Griffith said, “it is critical to recognize that the goal is not to make short-term behavior changes but life-long lifestyle changes. This can include clarifying if the role of the barbershop is to provide short-term information, programs, and screenings or to be equipped and funded to be a long-term community health resource.”

Author

More LDI News

Experiences of Patients With Disabilities Can Inform How to Improve Care

Patients Perceive Gaps in Communication and Disrespect During Health Care Visits According to a National Survey

Medicaid’s Role in Health and in the Health Care Landscape

LDI Expert Insights and Key Takeaways from Select Publications

AI Scribes: Can Technology Do More Than Free Doctors From Data Entry?

A Penn Lab Takes a New Approach to Unpacking the Doctor-Patient Encounter

Chart of the Day: Health Care Profits Increasingly Support Shareholder Payouts

$2.6 Trillion From Publicly Traded Companies Went to Dividends and Stock Buybacks, LDI Study Shows

How Corporatization Continues to Change U.S. Health Care

Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Featured Top Experts Analyzing the Issues

Research Brief: Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans Linked to Use of Inferior Hospice Care

People Dually Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are More Likely to Get Care From Poorer Quality Hospices