In deep times of sorrow and catastrophe, some of us flee. We flee either because we don’t want to face the weight and ugliness of the horror — willed ignorance — or we flee because we need a reprieve. I find myself needing a reprieve, though I’m by no means beyond the trappings of the former. There are other times when I seek out the wisdom of those human beings who refused to turn their faces from forms of social terror and found strength to endure. Think here of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her powerful fight against the lynching of Black people as forms of white, twisted desire and an attempt to control Black freedom.

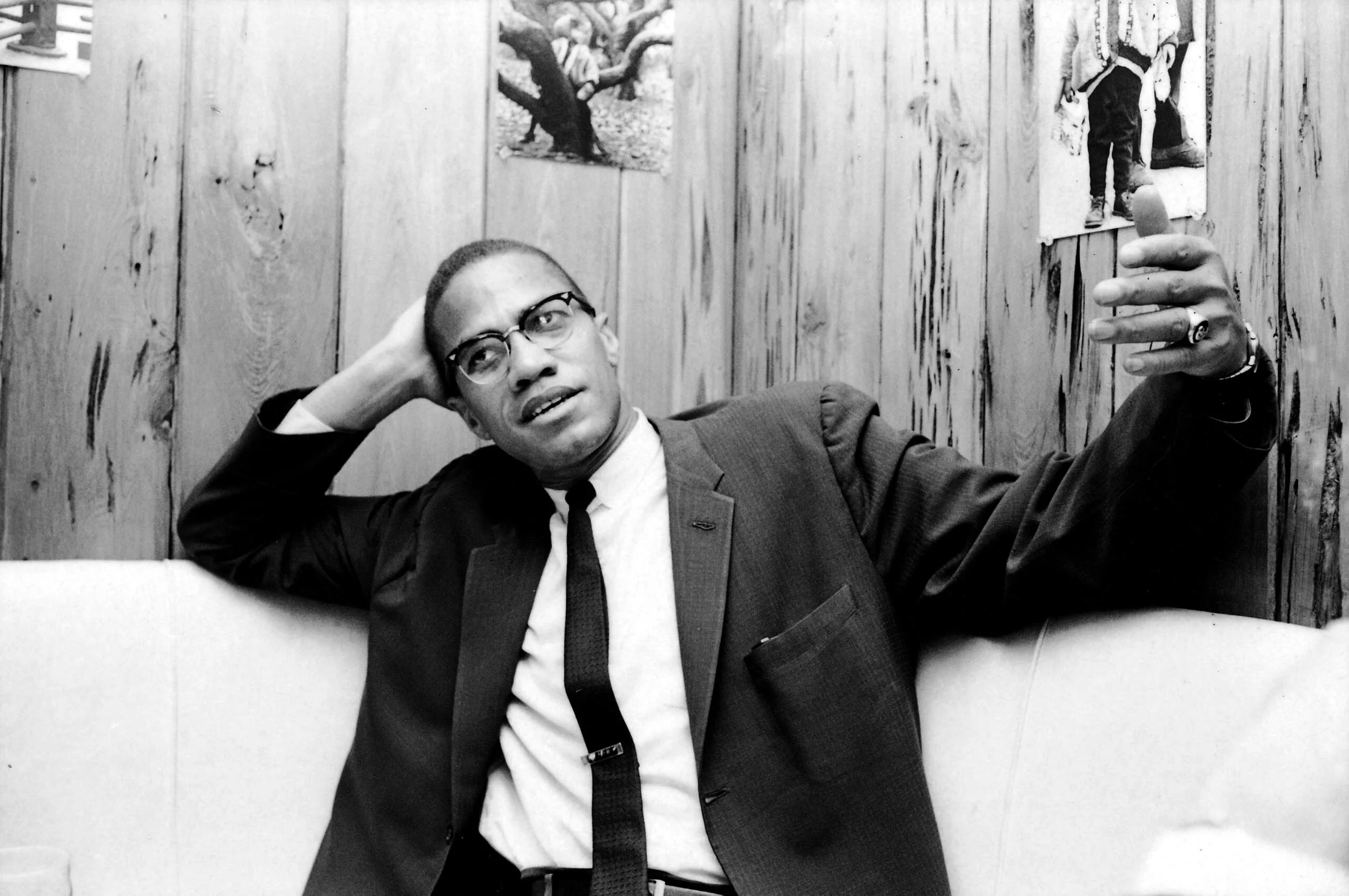

I recall as a teenager lying back on the floor listening to Malcolm X speeches on vinyl records that my father had collected. Malcolm X’s powerful and articulate voice encouraged me to read the dictionary, to embody the sting of his discourse, the truth that he spoke. I wanted to be like Malcolm X. I didn’t want to be a milquetoast person afraid to speak the truth. Many years later, I would read as much as I could get my hands on by and about Malcolm X. I found that many people were more interested in donning the X as opposed to understanding the complexity of the man. In 1991, I had the good fortune to meet Malcolm’s wife, Betty Shabazz, who also happily signed my copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I also had the deep honor of meeting Malcolm’s youngest brother, Robert Little, in 1993. He and I spent deep quality time discussing Malcolm.

As I was thinking about the horrors taking place in Gaza, the Black Lives Matter movement, and so much more, I thought of Malcolm, his wisdom and his indefatigable courage. Wondering what Malcolm thought about the crucible of this moment, while understanding the potential mistakes involved in presentism, or where we judge the past using dominant attitudes from the present, I turned to scholar Michael Sawyer. Sawyer is an associate professor of African American Literature and Culture, a faculty affiliate of Africana Studies and the Director of Graduate Studies of the Department of English at the University of Pittsburgh, as well as the author of the groundbreaking book, Black Minded: The Political Philosophy of Malcolm X. We discussed what Malcolm X means to us today and why his thought continues to be powerfully germane. The interview that follows has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

George Yancy: When I say the name of Malcolm X (who later took the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) in the context of the college classroom, I find that many students mistakenly associate him with advocacy for wanton violence. But in Malcolm X Speaks (edited by George Breitman), Malcolm X is clear about how he understands violence. He says, “I have never advocated any violence. I have only said that Black people who are the victims of organized violence perpetrated upon us by the Klan, the Citizens’ Councils, and many other forms, should defend ourselves. And when I say we should defend ourselves against the violence of others, they use their press skillfully to make the world think that I am calling for violence, period.” Black self-defense — to take a stand against Black brutalization and oppression — for Malcolm X, is not the same as white terrorism, which is predicated upon the hatred of Black people, their dehumanization and disposability. Malcolm X reminds me of the distinction made between terrorism and the collective struggle against oppression maintained by the Palestinian American activist and scholar Edward Said.

Said is clear that terrorism or the emphasis on armed struggle that is indiscriminate and “sometimes foolishly and in a political sense stupidly relied on” is unacceptable. Said would not accept the killing of innocent civilians. But he was supportive of the struggle against oppression. It is not lost on me that Patrick Henry, who was one of the “founding fathers” of the United States and a famous orator, was against the hegemonic British rule over the American colonies. Indeed, he is known as saying, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” I imagine that the Black people that he enslaved would have been killed had they made such a fiery and insurrectionist claim against slavery and their so-called white masters. That brings me to my main question. Black people continue to live under conditions of anti-Black racism. Yet, when we resist, we are seen as violent. We can’t fight against anti-Blackness in the name of liberty where this might mean deciding to die in the process.

Talk about how Malcolm X would frame the contradictions that I’m suggesting. How might he propose that we collectively think about resisting anti-Black racism in the U.S. in the 21st century? And how might he propose Black people support other collective groups that have been negatively racialized and othered under colonial and oppressive conditions? I’m thinking here specifically of Palestinians. Malcolm X was critical of the dispossession of Palestinians, writing: “Did the Zionists have the legal or moral right to invade Arab Palestine, uproot its Arab citizens from their homes and seize all Arab property for themselves just based on the ‘religious’ claim that their forefathers lived there thousands of years ago? Only a thousand years ago the Moors lived in Spain. Would this give the Moors the legal and moral right to invade the Iberian Peninsula, drive out its Spanish citizens, and then set up a Moroccan nation where Spain used to be, as the European Zionists have done to our Arab brothers and sisters in Palestine?”

Michael E. Sawyer: First, George, I want to thank you for the opportunity to be in dialogue with you on this platform, especially as we prepare for the 100th anniversary of the birth of Malcolm X on May 19, 2024. The thrust of your question is timely and provocative in that it deals with the unspeakable violence we are all witness to in the conflict between Israel and putatively Hamas. I say putatively because the carnage we have witnessed is, in toto, skewed towards those we understand to be non-combatants. As we situate ourselves to deal with this question through the thinking of Malcolm X, we will have to develop some abstract understandings of several terms: violence vs. nonviolence, resistance, and something that approximates the right (or perhaps the necessity) to resist regimes of oppression, whether they be state-sanctioned or not.

Abstractly, Malcolm X insists upon a very careful, what I will call a “distinct-indistinction,” between violence and nonviolence as forms of resistance on the part of oppressed subjects. Broadly, he forces us to realize that as far as systems of power are concerned, any activity that is designed to destabilize structures of power are deemed “violent.” Meaning that all technologies of resistance — say, for instance, speech acts against a regime — are reacted to, or at least categorized, in the same manner as an armed insurgency. This means that as a practical matter, the telos [or end goal] of any form of protest — let’s use the term “disruptive activity” — will almost universally first be characterized as violent and then reacted to in violent fashion. That is, the abstraction I referenced above that needs to be further glossed as also distinct from acts of self-defense against violence which Malcolm X understands as required to be violent. That abstraction allows us to deal with the specificity of your question that I take to situate, and I believe this to be correct, the plight of Palestinians as inextricably related to the denial of liberty to Black people in this country.

That linkage is, in my estimation, one of the foundational advances provided by the philosophical system (if you will allow me that) Malcolm X developed in that he understands “Black” to reference aggrieved subjects wherever and whoever they might be; a form of global transnational and trans-subjective Blackness. What that means, returning to the abstraction developed above, is that resistance to the occupation of Gaza or the West Bank by anyone will necessarily be seen as violent by the state of Israel. And I want to take care to acknowledge that there are actors within that government who do not subscribe to this view, and are reacted to violently. That means that a terror attack like that on October 7 by Hamas and others will be understood as a kind of capstone in a logic of violence, whether individual acts in that chain of events can be characterized as violent or not.

What this seems to assert is that the answer to the totality of your question regarding what is to be done to effectively oppose systems of state-sanctioned oppression is to mount a structural/systemic response to the structural/systemic refraction of all protest into acts of violence that necessarily tend to blur and, at the same time, magnify actual acts of violence. What Malcolm X endeavors to do through his transnational and trans-subjective understanding of Black(ness) was to create a type of super-citizenship that enjoyed the protection of recognized states for those situated within crucibles of oppression wherever that might be. This becomes Black Panther Party orthodoxy in that oppressed African Americans were deemed to be substantively existing in colonies and therefore colonized. Here, “super” is in great measure meant to be something like “greater than” but also shorthand for “superseding” in that it is an overarching understanding that invalidates typologies of citizenship that are designed only to render subjects objects in terms of the law: acted upon rather than protected by. This would be the kinetic realization of the dormant or potential power of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other prohibitions against apartheid, etc. Aggrieved parties would have the ability, or more accurately already be understood to be protected and if necessary, dynamically so by international peace-keepers dedicated to a realization of the term “liberty” that hovers over this discussion. We are disconcertingly far from realizing that goal.

Part of how I think about anti-Black racism is through the lens of white supremacy, though I don’t limit my understanding of anti-Blackness to white groups such as Christian Identity, neo-Nazis or “alt-right” Republicans. Whiteness is not limited to overt hatred or conscious racial discrimination or the use of the N-word. White hegemony, white power and white privilege are systemic. Even poor white people get to benefit ontologically from being racially defined as white. In fact, to define white supremacy exclusively in terms of white hatred would exclude those white people who continue to reap the benefits from a system that dehumanizes Black people and other racially minoritized people. Whiteness functions to conceal its power through mundane processes that are structured as “normal.” To challenge white supremacy, one has to challenge the commonplace ways in which whiteness continues to operate and accrue a sense of safety for white people — being able to drive while white and feel no anxiety about being pulled over because one is white, shopping while white and not being racially profiled, and never needing to teach one’s white children about how to behave in the presence of police officers for fear that one is immediately suspected of being a “criminal.” As white educator Peggy McIntosh says, “In my class and place, I did not see myself as racist because I was taught to recognize racism only in individual acts of meanness by members of my group, never in invisible systems conferring unsought racial dominance on my group from birth.”

I find that when my white students discuss white supremacy, they limit their critiques to forms of discrete hatred or meanness. Encouraging them to rethink white supremacy through a systemic lens, where anti-Blackness is indissociable from whiteness as a structure, they become almost nihilistic or fatalistic, which is never my aim. I do want them to lean into the conundrum of what it means to be white and yet ethical under a system of anti-Blackness where they are complicit. That is crucial. For me, to undo the system of white supremacy would entail undoing whiteness as a site of hegemony and privilege.

On March 19, 1964, Black jazz critic A. B. Spellman asked Malcolm X about his use of the term “revolution” and if such a thing was occurring in the U.S. at that time. Malcolm X responded, “There hasn’t been. The people who are involved in a revolution don’t become a part of the system —they destroy the system; they change the system. The genuine word for a revolution is Umwälzung which means a complete overturning and a complete change.” As we grapple with white supremacy at this moment in the U.S., especially in terms of the unabashed white nationalist ethos that Donald Trump has explicitly galvanized, how might the words of Malcolm X instigate more radical thinking amongst white people themselves in terms of what it would take to rid the U.S. or even the world of white supremacy? What would Malcolm X require of white people when it comes to radically undoing/overthrowing the system that underwrites their whiteness; indeed, white ontology?

As I mention in my book, Black Minded, which is the impetus for this discussion, for Malcolm X, all roads lead to revolution. What this requires is that the spirit of your insightful reference to Malcolm X’s use of the term Umwälzung be unpacked. We first must disabuse ourselves of the predisposition to characterize all forms of disruption as revolutionary or revolution. So, to situate revolution as the genus of radical activity rather than a species of it is to make a categorical error that comes with dire consequences.

Briefly, if you think of a Lamborghini as the genus of car rather than a species of car, at least two bad things can happen. First, you won’t recognize other cars, or second, you might expect all things called “cars” to perform like Lamborghinis. So, if I think that all modalities of radicalism or radical activity — or perhaps more accurately, forms of disruption — are revolutionary, then I can miss things that don’t look like what I require them to look like that are in fact revolutionary and/or expect things like demonstrations to perform like revolution. Circling back and refining what I said about Malcolm X understanding all roads to lead to revolution is to understand just that. The road from Chicago to LA isn’t in LA when you first pull onto Route 66. There are miles to cover and things that have to happen and you may not make it, but these are steps in a particular direction. Any step toward the telos of revolution is understood to always already be revolutionary or violent and is thus obstructed. All of this is ably though incompletely taken up in Bernard Yack’s The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, which basically asserts that a preoccupation with a romanticized understanding of the French Revolution makes it impossible for us, in the aftermath of that chaos, to accurately characterize acts of protest against structured power; and here I want “characterize” to do a lot of work. I need it to mean the ability to properly plan, execute, witness, categorize and manage expectations. So, to me, what Malcolm X is saying is: Don’t expect a demonstration to upend a system and don’t be surprised when an actual act of revolution causes complete upheaval, which may not necessarily be what people are hoping for: colloquially, everyone wants to have a revolution, but nobody wants to clean up afterwards.

So, getting back to where you started, what you are describing to me with respect to students’ disaggregating commonplace complicity with white supremacy and anti-Blackness as unrelated from more dynamic forms of racial hatred is the result of another categorical error. So, if we understand whiteness and everything that comes with it as the genus, complicity with those benefits as well as actively functioning as a racist are species of whiteness that can be interrogated separately but understood to be related to one another in that whiteness understood in this fashion is the threshold condition for things that fall under it and to your point “where anti-Blackness is indissociable from whiteness as a structure.”

To get to the closing moments of this question, which is what needs to be done to begin to develop a program for the eradication of white supremacy globally, would first require that we have an informed reexamination of events. I mean something as basic as perhaps being willing to understand that the American Revolution was not a revolution, but rather something that approximates a civil war that was predicated upon refining the functioning of white supremacy outside of continental Europe. That continued with the Civil War in the 19th century, and Trumpism represents an attempt to revitalize essential elements of that practice that had been suppressed in the late 20th century. This reasserts that anti-Blackness that begins as chattel slavery and reverberates and evolves is the engine of white supremacy. To dismantle or render inoperative anti-Blackness would impair white supremacy. What that means is that white people must necessarily be willing to address the genus of whiteness that would be evacuated of its force by actively first understanding something as basic as that Black people exist outside of the necessity of what Toni Morrison understands as the “white gaze.”

Malcolm X also said that “the Negro Revolution is no revolution because it condemns the system and then asks the system that it has condemned to accept them into their system.” While I don’t see myself as a revolutionary (unless to be a revolutionary means that I am prepared to fight for love of the whole of humanity and the Earth), how might we as Black academics rethink ways in which we uncritically accept aspects of the system of white racial capitalism? For example, as professors, how might we change the system when we are in many ways part of the professional managerial class? I’m trying to be honest here, taking Malcolm X at his word.

This formulation on the part of Malcolm X that refines the term “Revolution” with the modifier “Negro” is, in many ways, Malcolm X at his best. I say that to mean the way Malcolm turns to Black people and endeavors for us to redefine ourselves as the first step toward something that I want to call Self-Authorized Blackness. Malcolm X understands the term Negro to be more than pejorative but to represent the verbalization of the debasement of Black identity that unmoors it from referents that aren’t dictated by white supremacy. You see this most exemplified by his refusal in multiple public forums to allow white people to force him to utter what he understood as his “slave name.” That’s something that Negros do, not Black People, and as a necessary product of that claim, revolution that seeks to find subjects welcomed by the very system that made the revolution necessary in the first place is a waste of time, and worse, tends to reify the problem. So, to get at your really difficult question, what we need to do as Black academics as distinct from what Malcolm X would pejoratively understand as Negro academics is to exhibit the type of bravery, intellectual and otherwise, that he exemplified. That means — and this is to mechanically adopt everything we have been talking about here — calling things what they are, and in so doing, having the proper expectations for them. For me, that means the work we do within the structure of the university itself that I’m using as a master signifier for the business of Western thought, not necessarily the substance of it, can be disruptive, demonstrative and provocative, but probably not revolutionary. I don’t think it’s an accident that so many important movements begin on campuses and then find themselves facing outward but never forgetting that beginning. I think that it is incumbent upon actors within the academy who are serious about the kind of disruption we are understanding Malcolm X to be demanding of us to be diligent about maintaining a relationship to what I want to call The Black Commons. Not as a hierarchical referent but to understand that space as the place where the theory of revolutionary disruption of the status quo can be put into practice.

Malcolm X stressed the importance of the necessity of Black people loving themselves. He understood the importance of the complex and toxic ways in which Black people had internalized what I have theorized as the white gaze. It is a gaze that is part of a larger epistemic structure that refuses to see Black people as human and deserving of respect. His love for Black people didn’t just end after he parted ways with the Nation of Islam. He continued to teach Black people the importance of decolonizing their minds, of freeing themselves from the lies and myths that were designed to keep them oppressed. Philosophically, Malcolm X emphasized a counter-narrative that uplifts Black dignity and Black existential and cultural vibrancy. He spoke unambiguously about the ineradicable value of Black life. Malcolm X’s message predates the contemporary manifestation of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. In what ways do you see Malcolm X’s political and cultural philosophy as a precursor to BLM?

Ishmael Reed, during an event memorializing Max Roach’s We Insist!: Freedom Now Suite at Harlem Stage, proposed that Black Studies became necessary in the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X. I don’t disagree with that, but want to use your question to further pull that thread and say that the mirror that Malcolm X held up to the world generally and Black folks in particular was meant to position us to study Blackness from a perspective of the kind of love you are drawing our attention to with this question. I think your marshaling of your theorization of the white gaze resonates with what I gestured at with bringing Morrison to the conversation. What I mean by putting you in conversation with Morrison and Malcolm X is to propose that the eradication of the white gaze is to resolve the deleterious effects of the misapprehension of true identity (self-consciousness) that W. E. B. Du Bois begins with when he insists that double consciousness “…only lets [Black people] see [themselves] through the revelation of the other world.” Malcolm, Morrison and you want to do (when I say “do” I mean “be” in the philosophical sense of “Being”) different. When I say different, I mean to move beyond a definition of Being that has been hijacked by white supremacy and anti-Blackness. Instead, the three of you start from a perspective of Love for Black people rather than hate.

This is important for a bunch of reasons, but significantly I want to lean into the notion of Malcolm X as beginning and ending with Love to deal with the misapprehension of him as angry and violent; a minister of hate as he was often labeled. To Love Black People in the context of negatively framed Blackness in what I have called the coercive crucible of white supremacy and anti-Blackness is disruptive and deemed violent. This is why the concept of Black Life “Mattering” was met at best with derision and at worst with violence. That is the substance, violence, of the Blue Lives Matter response to the slogan Black Lives Matter. It’s a threat, and one that has to be taken seriously in that it isn’t a meta threat but a physical one. So, in the same way that Reed sees Malcolm X’s death as the necessary and sufficient catalyst for Black Studies, I would propose that his notion of Black Love for the Black Self is the framework upon which BLM, the concept, hangs. Malcolm’s call to love your Black self is necessarily a presupposition of the fact that Black people matter in positive ways and not to matter in only being demonstrated to not matter, resonating with Giorgio Agamben’s consideration of the homo sacer.

What becomes clear to me is that Malcolm X’s aim — which was certainly impacted by the teachings of the honorable Elijah Muhammad — was to rethink the semiotics of Blackness, to rethink the political, economic and ideological rendering of the Black body as slavish. In a talk that Malcolm X gave at the University of Ghana on May 13, 1964, he said, “Either you are a citizen or you are not a citizen at all. If you are a citizen, you are free; if you are not a citizen, you are a slave.” As I thought about this quote, I wondered what Malcolm X would think about Afropessimism. Despite the power of his message, its legacy, it is certainly clear that many Black people continue to doubt their status as “citizens” given the continued anti-Black practices within the U.S. Clearly, George Floyd died at the hands of an empire that regards Black life on the cheap. Black people continue to be exposed to gratuitous violence, are subjected to general dishonor, and their children are taken from them through so many death-dealing ways (shot and murdered unarmed, incarcerated, rendered abject through medical racism and child welfare). How might Malcolm X sustain a conceptualization of Blackness as freedom through such pervasive anti-Black hydraulics, especially given the challenging and powerful claim articulated by scholar Frank Wilderson that “Blackness is coterminous with slaveness.”

I want to begin at the end of your question with Professor Wilderson’s assertion that “Blackness is coterminous with slaveness.” I really need to gloss this, and I want to do that through everything we have been saying about Malcolm X’s love for Black people and being Black. If by that assertion, Wilderson means that Blackness as framed by white supremacy — and here I’m thinking of what Du Bois says about the inability to know the self when viewing the self through the framework of those dedicated to your destruction — then I would agree that Blackness as such under those conditions can appear to be coterminous with slaveness. I believe Malcolm X and I also want to do something different and say that what I would call Negatively Framed Blackness is conterminous with “slaveness” and Blackness qua Blackness is the interruption of that binary without the necessity of dialectical interaction. This is the mirror that Malcolm holds up for the use of Black people. A mirror that allows self-reflection and authorization that meets that Black subject at the point of their own positive eruption that happens beyond the boundary of, back to your term, the white gaze. I agree with Wilderson in that so long as we countenance the capturing of important terms like Being, Subject, Human, Ontology, etc. by white supremacists, then we are indeed trapped in that semiotic funhouse. This is the rethinking of semiotics of Blackness that you put into play. This is the substance of your provocation in the question above that deals with the difference between Negro Revolution and Black Revolution.

I would say that for me, participating in a linguistic regime that refuses the existence of Blackness as a positive vibration is to accept the totalizing nature of the system of white supremacy and I refuse that. I insist that there was Blackness as a positive way of Being before the Middle Passage and Malcolm X’s loving on Black people in order to insist on us loving ourselves is Black Revolution then, now, and in the future. I love the phrase “pervasive anti-Black hydraulics” because it speaks to the mechanical way I see the world, and linguistically insists that there is a pervasive Black hydraulic pulsing away that, again, I want to assert is not designed, constructed, operated or maintained in dialectical congress with white supremacy or anti-Blackness.

To that end — and this is a part of your question I don’t want to miss dealing with — I think Malcolm X would see Afropessimism as an essential step in the long march toward the type of Revolutionary Blackness he insists upon that is not preoccupied with but fully aware of the framework that discourse so accurately maps. I don’t believe that Negatively Framed Blackness or Negative Black Being is either ontologically or the telos of Blackness, and I don’t want to have that sound Pollyannaish but rather a position of aspiration informed by the dogged durability of Black people under the dire conditions of threat that you have referenced here. That’s why I get up in the morning. To me, that is why you put in the effort to produce these conversations and why I took the time to try to participate in a manner that is I hope useful. Thank you so much for this opportunity.