The crack epidemic has passed into legend since its end in the mid-1990s, and the further we get from its height, the larger it looms in the collective imagination. That’s partly a product of memory itself, it seems, but it’s also a consequence of which memories of the epidemic have been prioritized.

For more than three decades, the accounts of law-enforcement officials, politicians, and pundits have dominated the conversation. Most of those people were never touched in personal ways by the epidemic, except perhaps for what they did at work or saw in the news or experienced in passing. For those people, the crack epidemic was and continues to be an idea that encapsulates everything bad about the ’80s and ’90s—the poverty, crime, gangs, violence, everything the ghetto represented in America after the civil-rights movement.

But for the community members who came face-to-face with the crack epidemic, it was as real as flesh and blood. Crack and its attendant misery permeated every aspect of our lives. For us, the crack epidemic was more than a collection of statistics used in an article or speech. It was embedded in our neighborhoods and homes. It was in some people’s childhoods, interrupted constantly by trauma, tragedy, threats, and stress.

Michelle lived just a few doors down the block from my family, in Columbus, Ohio. I hardly ever saw her, though. In fact, I don’t remember ever actually meeting Michelle, but I was taught to be afraid of her. My mom, a cautious woman who otherwise avoided gossip, would drag our house phone room to room by its long white cord and talk at length with her friends about Michelle From Down the Street.

She had too many strange people going in and out of her house. The neighborhood could hear her parties at all hours of the night. She looked “a mess.” It was all “just so sad,” my mom would say with a slow shake of her head. She would move on to other topics, but I stayed fixed on Michelle and tried to imagine what might be going on just a few feet away.

One Sunday afternoon, I was sitting on our front porch with my older sister when a van pulled up and parked in front of Michelle’s place. Out of it came an older woman and a young girl, each resembling our mysterious neighbor in her own way. Because my sister knew everything, I asked her who the strangers were. “Duh! That’s Michelle’s family,” she said, adding that the small girl was Michelle’s daughter. “Why don’t she live with her mom?” I asked. My sister shrugged her shoulders, annoyed, like it was the kind of inconsequential question she’d never ask, and answered, “I don’t know. Probably because Michelle is a crackhead.”

It was 1993 or 1994. I was just 5 or 6 years old but had heard the word crackhead countless times, usually from other kids. Crackhead was a go-to insult—so-and-so was “acting like a crackhead”; “yo mama” was a “crackhead.”

It was popular, I assume, because it belonged to the grown-up world, and using it made us feel grown. I suppose we made crackhead a slur because we feared what it represented, a rock bottom to which any of us could sink. That’s what children do when they’re in search of power over things that frighten them: They reduce them to words, bite-size things that can be spat out at a moment’s notice.

I couldn’t make sense of the fact that Michelle was a crackhead. She lived just down the street, after all, and she had a family. Crackheads were supposed to be foreigners from some netherworld, whose main activities were begging for money and otherwise disrupting community life. Then they were supposed to return to wherever they came from—alleyways, sewers, wherever the trash went after we threw it out.

Michelle disappeared from the neighborhood sometime soon after her supposed daughter came to visit. She was replaced quickly by other people who lived on the margins of our poor Black community. There was the thin light-skinned woman I’d see sometimes around the convenience store at the end of our street. Al, the older man who owned and operated the store, called the woman “Miss Prissy.”

There was a man whose name I never knew, who walked up and down the streets, always in a hurry and always selling something—bags of loose fireworks in the summer, brand-new down coats in the winter. Like with Michelle, the adults I knew only talked with him and Prissy in passing. I did the math and concluded they were also “crackheads.”

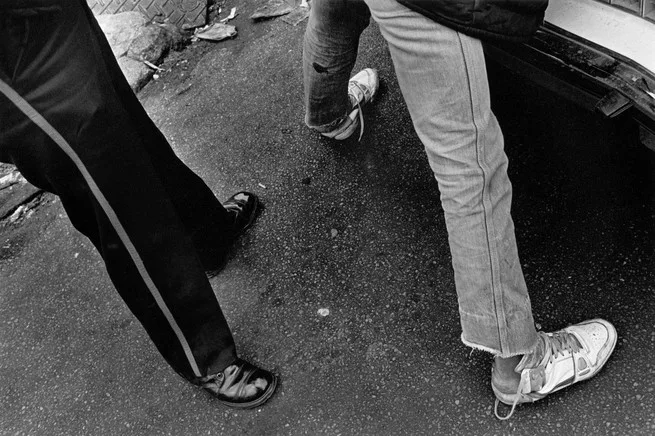

That type of calculus, I imagine, was common for lots of kids who grew up like me—poor and Black in the midst of the crack epidemic of the ’80s and ’90s. There were things happening all around us that we knew better than to ask about. My mother had a policy: Mind your business. That’s exactly what she’d say when she’d catch me stealing glances at the older boys on the corner—“Mind your business.” It was like growing up in a steel town where nobody talked about steel.

I surveyed my community and saw crack’s devastation and residue everywhere. I saw crack’s effects in the way my neighborhood was policed, as though a dragnet had been cast over us. The police seemingly wouldn’t be satisfied until everyone I knew had been stopped, questioned, searched for drugs and weapons, detained, fined, arrested, jailed, inconvenienced, awakened in the middle of the night, humiliated. Some people would end up beaten, shot, or killed, but all of us would be touched by this crack-era policing.

School felt like an extension of the streets. There, it was teachers, mostly white, who did the profiling. They labeled my classmates “emotionally disturbed” or “hyperactive,” diagnosed them with learning disabilities and dismissed them accordingly. For us boys, Black boys, it was a creeping process that engaged as we got bigger and more spirited. We couldn’t name it, but we recognized the disdain and bristled at it. We didn’t realize we were inside the belly of a beast that ate insubordinate Black boys whole, one that labeled our resistance as insubordination to justify itself to itself.

I don’t think my peers understood the effect of the crack epidemic on us young people at the time. I certainly didn’t. Crack’s shadow was something we just understood we had to navigate. It threatened to envelop us, but we did our best to outrun it. We avoided the police who profiled us as drug dealers and gangbangers.

The crack epidemic ended, and I survived its fallout by some combination of striving, luck, my mother’s mothering, and God’s grace. The further we got from the crack era, the more the panic around crack was replaced with panic over terrorism and other 21st-century American crises.

Most everything Americans know about crack comes to us in the form of myth, stereotype, and innuendo. When the crack epidemic is mentioned now, it’s usually as a punch line. Crack as a superdrug, dealers as superpredators, irredeemable crackheads and crack babies all get evoked to prove a point. Or they’re referenced like fads of the late 20th century—like Dynasty, shoulder pads, and acid-washed jeans.

There are, of course, other common uses of the crack epidemic. Politicians brandish it like a shield, to both deflect and intimidate. In speeches, they invoke our national memory of the frightful period as an argument to maintain our criminal-justice system. Or they use it to justify their role in a number of poor policy decisions related to Black life and death.

But some of us want answers. We want to reconcile our memory with all we’ve learned from popular culture about the crack era. We are piecing together fragments toward a real history.

What I’ve learned, through hundreds of interviews and years of research, is that what crack really did was expose every vulnerability of society. The disaffection caused by poverty and powerlessness led to rampant drug abuse in a generation of young people, people who fell right through the holes in our social safety net and social contract. The crack epidemic exposed just how broken the most vulnerable were in the 1980s and ’90s, just how little the rest of the nation cared, how people would rather disappear their fellow Americans than help them. Crack marshaled society’s worst instincts—greed, fear, shame—in response.

But I also learned that even a substance as powerful as crack was no match for the resilience of Black people hell-bent on keeping one another, and their community, alive.

I think often of Michelle From Down the Street and wonder what became of her. I like to imagine that she left the neighborhood for treatment. That she got clean and moved into a big house with her daughter, who can’t remember a time when they weren’t attached at the hip.

Years of covering the criminal legal system tell me that outcome is unlikely, though. It’s more probable that Michelle was arrested and gobbled up by the system. If she is alive today and clean, she probably lives with the residue of the epidemic—a criminal record, chronic illness, trauma, guilt, shame.

For her sake and that of so many others, it’s past time that we reconcile the crack epidemic with the rest of history. To move forward, we must confront the legacy of the crack epidemic with honesty and empathy. We must take its measure, make meaning of it, and incorporate that meaning into the greater story of who we are. By doing so, we can work toward healing and justice, ensuring that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

This essay has been adapted from Donovan X. Ramsey’s book, When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.