Wes Moore Would Like to Make History

Wes Moore, who is currently America’s lone Black governor, works from a creaky-floored second-story office in the Maryland State House. The building—Georgian brick, shaded by giant trees, in the quiet center of Annapolis—is a small icon of American history. It is the only statehouse to have served as the nation’s capitol. (The Continental Congress, meeting there in 1784, ratified the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War and established the United States.) The building holds bronze statues of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, who were born, and enslaved, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Moore can seem surprised to find himself in the governor’s office, though the swerving path of his life has been a defining feature of his rise. He spent his early childhood in Takoma Park, a suburb of Washington, D.C. His great-grandfather emigrated from Jamaica, in the nineteen-twenties, but went back after he was threatened by the Ku Klux Klan; his son, Moore’s grandfather, returned to the United States. When Moore was three, his father died of an illness, and his mother, a freelance writer, moved with her three children to live with her parents in the Bronx. She enrolled Moore at Riverdale Country School, an exclusive private school, but as a teen-ager he had a run-in with police, and, after more trouble, he was threatened with suspension; his mother sent him off to Valley Forge Military Academy and College. He thrived there, joined the Army, and enrolled at Johns Hopkins University, where he graduated in 2001. He went to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship, and worked at Deutsche Bank in London, before he rejoined the Army, as a captain, and deployed to Afghanistan, with the 82nd Airborne. In 2010, after a stint in investment banking, he became a minor celebrity for his book “The Other Wes Moore,” a best-seller about the divergent path of his life and that of a man with the same name, who went to prison. Eventually, Moore switched to nonprofit work, and, in 2017, he became the C.E.O. of the Robin Hood Foundation, an anti-poverty group based in New York.

Over the years, his story has attracted journalists and political prospectors. Oprah Winfrey became a friend; he met Barack Obama in the White House. But when Moore entered the Maryland governor’s race, in 2021, having never run for office, he faced a broad field of competitors, including Tom Perez, the chair of the Democratic National Committee, who was endorsed by the Washington Post and the Baltimore Sun. Initially, Moore was polling at one per cent. During the campaign, he was accused of having hyped the trials of his youth; in his book, though he never claimed to have been born in Baltimore, he described the two Wes Moores as plying “the same streets,” and he did not correct some interviewers who assumed that he had grown up in the city’s gritty sections. There were other efforts to challenge his candidacy: in an ugly episode, a prominent donor to one of his rivals circulated an e-mail arguing that Maryland voters would not elect a Black governor: “Three African-American males have run statewide for Governor and have lost. . . . This is a fact we must not ignore.” But Moore drew crucial endorsements from the teachers’ union and prominent Democratic officials, and attracted a fortune in donations, thanks in part to Winfrey, who appeared in advertisements and at a virtual fund-raiser. He narrowly won the primary and went on to trounce a far-right Republican, Dan Cox, who had hired buses to take people to Washington, D.C., for protests at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Moore would be Maryland’s first Black governor—and, instantly, a subject of prognostication about his potential for higher office.

On the morning of his inauguration, this past January, Moore arranged a ceremony a few hundred yards from the statehouse, at the Annapolis dock that once served as a receiving point for slave ships. To Moore, history is a complex partner in his politics; he often says that he didn’t run simply to make history, but he embraces the power of his breakthrough, and he has tried to convert that momentum into legislative progress against inequalities in education, employment, and wealth. In a recent speech at Morehouse College, he described Maryland as “the proving grounds of redlining and other discriminatory and predatory housing policies that have served as one of the greatest wealth thefts in our nation’s history.” Drawing on his experience in the military, he has also conceived of a civilian program for young people who seek a project larger than themselves. In his first year in office, he created a voluntary year of service for high-school graduates, which is in the spirit of AmeriCorps and which he hopes to make available to every student in Maryland. Signing the bill, he described service as a source of “civic bonds” that can keep people from “retreating to our corners of political ideology.”

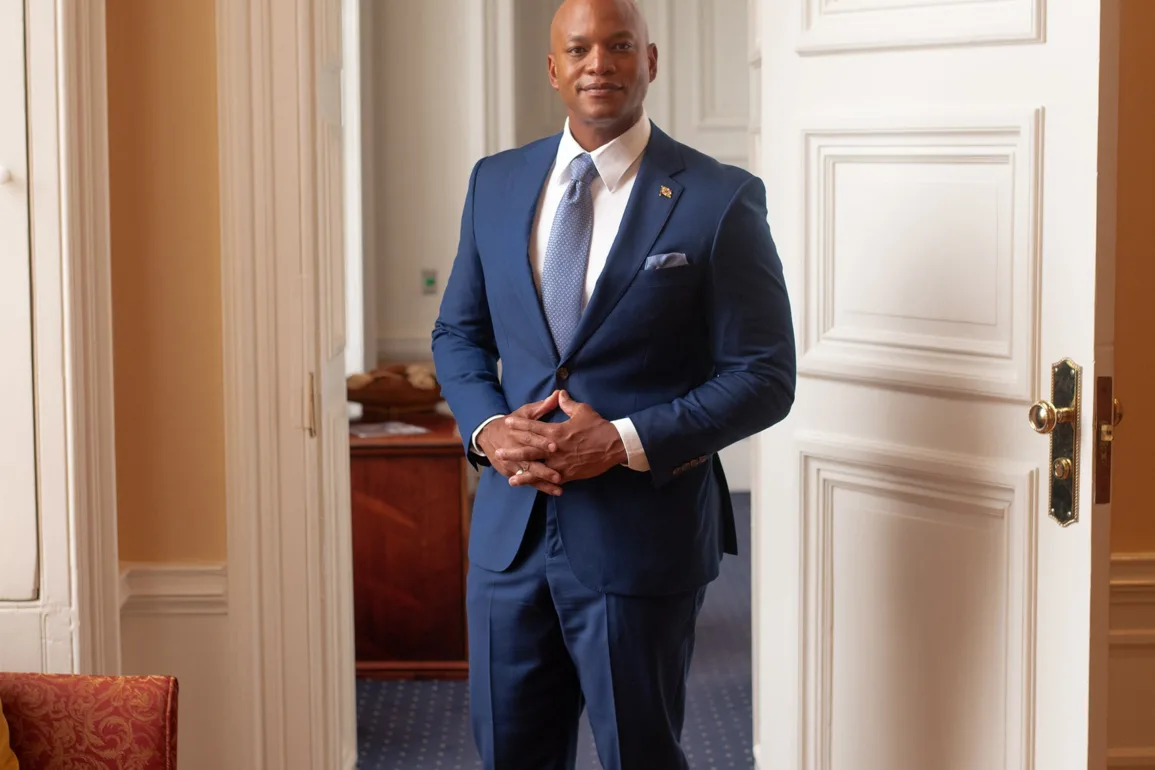

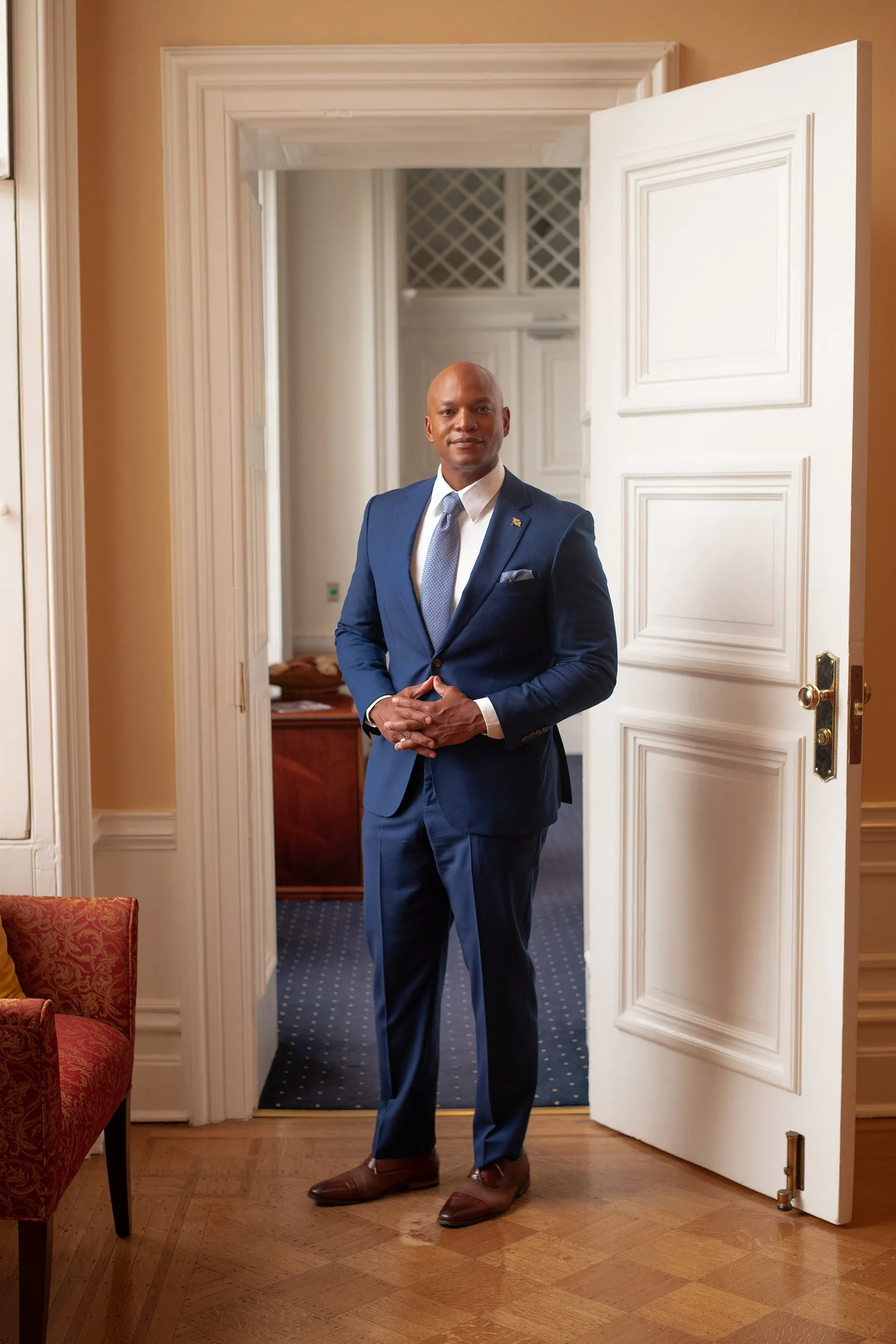

At forty-four, Moore is bald but boyish, and is built like a wide receiver, the position he played at Johns Hopkins. On camera, he can project relentless charm, but, in person, when he settles down, he is blunt and succinct. In February, Time wrote, “The Maryland governor may be the Democrats’ most talented newcomer since Barack Obama.” When I visited Moore recently—to talk about service and greed, unity and polarization—the walls of his office were still sparsely decorated, except for some notable historic items, and we started there. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you help me get a feel for where we are right now? Has this always been the governor’s office?

This has always been the governor’s office. And, at four months, we’re still getting things on the walls. But maybe my favorite thing on the wall that I didn’t bring is that. [He points to a case holding an old document.] That’s George Washington’s handwritten resignation of his commission [as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army]. Downstairs, inside the rotunda, is where George Washington, for the first time in the history of the country, willingly gave up power and said, “The power is not mine. The power belongs to the people. And I don’t get to choose who leads. The people do.” And it really did set the foundation for every election we’ve ever had since. It is the foundation of democracy.

Consent, ultimately. The willingness to lose.

And your willingness to accept the results shouldn’t depend on the results. And so I love that document up there, both because I found myself running against an election denier and [because] it just shows how tenuous democracy is. We’re not that far today from fundamental political questions: What is democracy? And what results do we accept and what don’t we? [Moore points to another item on the wall, the photo of his swearing-in.] And then, right there, is when I was being sworn in as the sixty-third governor. Look at that dynamic, that arc.

You started that day at the city dock?

It was very intentional. It’s partly a tribute to Alex Haley and to “Roots,” because his family traced back to Annapolis. So I said, “I want to start the day there.” And so myself, the lieutenant governor, and a couple hundred people all met down at the dock, and we had a moment of silence. Then we basically marched from the docks up to the statehouse, which is a short march in terms of geography, but we really wanted to highlight the power of the journey. The statehouse was built by enslaved people. So now I was about to get sworn in as the sixty-third governor of a state, literally in front of a building that was built by the hands of those who were enslaved.

What was the reaction?

Immediately, the attacks started coming. It was, like, “He’s using his first moments for indoctrination.” You realize how a moment that was intended to unify was being twisted, as Kipling, who is one of my favorite poets, wrote: “Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools.” I was very clear, and I said, “I didn’t start the day that way in order to make people feel minimized. I started the day to make people feel empowered.” And I didn’t do it because I wanted to create some measure of separation. I actually wanted to show the power of inclusion. The power of this journey is it’s been a collective one.

By now, there’s not a whole lot that surprises you about our political moment, but did you figure that maybe the dock gesture would not go across in the way that you intended? Does the negative response make you say, “O.K., maybe I need to take a half step in another direction”? I imagine the response was not the feeling you wanted.

It actually was. Because I think about another thing inside this office, which I love: that’s Frederick Douglass. [He points to a photograph of Douglass, peering to the side.] Young Frederick. I specifically wanted to position that picture in that spot for a reason. Because, when I’m sitting at the desk, I can look up at that picture and it actually looks like he’s looking at me, with this very pensive and this very grating look.

He’s watching.

He’s watching. I didn’t do [the dockside ceremony] because I thought that everybody would celebrate it, because I know there’s a lot of people, for their own individual motivations, who were not going to. I did it because it was important and it was right. And I try to keep that North Star, about not just that decision but for all of these decisions that we’re going to have to make. So I wasn’t surprised that there were certain individuals and networks and radio-show hosts who had a certain opinion about it. But I also knew that I wasn’t going to neglect what I thought was the most appropriate way to bring in this new era.

I remember a Douglass quote where he said something like wanting progress without struggle is to “want rain without thunder.”

And when you know and consider the history of Maryland, of the United States, this journey wasn’t a smooth one. This journey was an uneven one. This journey was one that caused a tremendous amount of conflict. And not even just physical conflict but internal conflict. It forced people to wrestle with things. It forced people to be introspective. And that wrestling made our society better. And so what we’re just asking in this moment is that our society continue to wrestle with the fact that there is still a measure of brokenness that has to be addressed.

I want to go back a bit into the family story, because it’s a nonlinear story, in some respects. Your great-grandfather went to college at Howard, but then returned to Jamaica?

My great-grandfather was in Sumter, South Carolina. He was a minister. And a very vocal minister. And, eventually, those threats started coming. And in the middle of the night he picked up his family, including my grandfather, who was a toddler at the time, and they left. And they didn’t just leave Carolina—they left the United States and they went back to Jamaica. And so most of my family has always said, “I will never come back to that country.” But my grandfather, because he was born here, he’s, like, “I’m an American.” And in all his humility [laughs], he was, like, “This country would be incomplete without me.” So he came back to the United States.

Back unto the breach.

Back unto the breach. He went to Lincoln University. Another H.B.C.U., in Pennsylvania. He got his degree, and became a minister. In fact, that shawl right there is the shawl he wore when he became the first Black minister in the history of the Dutch Reformed Church.

My grandmother was born in Cuba, and immigrated to Jamaica when she was twelve or thirteen. And eventually she met the preacher of the church that her family went to: this young minister, this “kid preacher,” as she called him, who was my grandfather. They fell in love; they got married. She immigrated to the U.S., and she became a public-school teacher for over forty years. And that was both of them in the Bronx.

Either in books or an interview, you said, “I grew up in a family of people who love this country, even if it didn’t always love them back.”

I never will miss a meal and I’ll never miss a bathroom. Those were both lessons I got from my grandmother, because she’s, like, “When you’re driving through the United States, you never know when the next place is going to allow you to use the bathroom. You never know when the next place is going to allow you to buy a meal.” And when my grandfather became a minister, the same threats that started coming to his father started coming to him. Same threats on his life, same threats on his family. And he stuck. And he was just, like, “No one has that power to run me out.”

Your father died when you were three. You moved to the Bronx. And the private school that you attended, Riverdale, was an interesting experience. You wrote, at one point, that you were “too ‘rich’ for the kids from the neighborhood and too ‘poor’ for the kids at school.” There’s a skill set in being able to go between different communities.

The code-switching.

Right.

My mother sent me to Riverdale. It was a huge sacrifice. She was working three jobs. But she was, like, “It’s the best school for my son, and it’s the kind of school I wish I could have gone to, and I’m going to do whatever it takes.” I never got my footing there. I never felt comfortable. And then you’re coming back to a neighborhood where now everyone’s testing you because you go to this private school. So you’re not winning anywhere.

You’re off balance.

You’re just consistently off balance. And then finally—I think my behavior justified it—my mother was, like, “I can’t do this anymore. I can’t keep watching this.” And that’s when she was, like, “I’m going to send you to a military school.” And she heard about Valley Forge through a friend from church. My mother was going around and she was asking friends and people, saying, “Hey, if you can help, dah-dah-dah-dah-dah.” And people would give what they could, but it’s not going to be thousands of dollars. And then, finally, my grandparents ended up mortgaging their home in order for my mother to have the money that she would need to send me off to that first year of school.

Your critics made hay about this question: “Where are you from?” There’s something about the combination of your qualities that makes people want to focus on this question about where you’re from. But how do you make sense of that question?

The reality is that, for a lot of people, “Where are you from?” is an easy question. And for me it was never an easy question, because I moved around a lot. I moved around a lot not because it was fun. We moved around a lot because of tragedy. So it was my family consistently moving for an opportunity, for a job, for support when my mom needed it. I think about it in context. When I talk about the importance of Baltimore, for example—my mother got her first job that gave her benefits when I was fourteen. The first job that allowed her to work one job instead of multiple jobs. And that job was at a place called the Annie E. Casey Foundation, in Baltimore. I’d been born in Maryland, but that was my first introduction to Baltimore. And that was the first place that I actually considered home. It was the first place that I felt actually accepted me for who I was, flaws and all. So many of my most important experiences and so many of my deepest friendships are from here. And so that’s why I always said, from a young age, “I’m a Baltimorean, through and through.”

If there was a period in your life where you became aware of your potential, it seems as if it was at Valley Forge—the notion that service was not just “O.K., there’s some nobility in the military” but the idea that it stitches you into other people. When did that become present in your imagination?

After the first year. Because the first year at Valley Forge was mandatory, and then I had a chance to go back to [a regular] school. And I was, like, “Actually, if it’s O.K., I’d like to stay.” And when asked, “Why did you choose to stay?”—one, I actually had tasted leadership for the first time. I think I was a lance corporal. [He pantomimes a puffed-out chest.] But I had responsibility now. And so there’s something truly addicting in that. The other piece was the people who I started school with at that point—Sean Fox, Tim Lansing, Josh Weikert—these are my people now. Even still, to this day, these are my people, because we’ve experienced really, really hard days and really challenging things. And so, when I knew they were going back, it then became easy for me. It was, like, “Well, I want to come back, too.”

“I’m not going to let them down.”

Those are my people. That started becoming a very consistent theme for me. Perfect example: when I had finished the Rhodes Scholarship, and I was working at Deutsche Bank, in investment banking, I was talking with then Major Mike Fenzel [a mentor and former football player at Johns Hopkins, who is now a major general in the Army]. He calls me up and he’s, like, “When are you going to get into the fight?” And his point was “These are your people out here. Where are you?”

You could have stayed on Wall Street, and I’m curious about what that experience taught you. How does it shape your understanding of profit, greed, opportunity?

I didn’t know anything about Wall Street, because I didn’t know anybody when I came up who was ever on Wall Street. My football coach at Johns Hopkins was a trader at Deutsche Bank in Baltimore, and, at night, he would coach Johns Hopkins football. He was the one who was first, like, “Hey, have you thought about doing anything in finance?” Because I studied international relations, econ, etc. He said, “You do understand that government is budgets? Where are you putting money? That is what’s important and what’s not.” And so he was, like, “If you really want to understand budgets, you should really go to a place that’s going to pay you to train you.” He set me up with an internship at Deutsche.

And I came in, and I was good at it. But, even though finance came very naturally to me, it wasn’t like I was fulfilled by it. They make finance sound a lot harder than it actually is. All the acronyms. As I found myself moving up on Wall Street, the higher I moved, the less fulfilling it became. I thought, I can’t see myself doing this. So that’s when I decided to leave. I think that the understanding of the financial system was helpful. And, at the same time, it also helped me to better understand the damage that I can cause for society.

In what way?

You cannot have a system that will make it complicated for people to be able to understand it. That punishes people that play by rules and lets off people who don’t. I was working in finance during the financial crisis, and I would listen to these conversations of bankers who were watching pensions evaporate, who were watching life savings go away, for the people who could least afford it. And I was hearing these conversations in which bankers were basically blaming schoolteachers who chose to buy a second home and did it on credit. It was, like, “Wow.” Because they’re describing my family members. They’re describing my friends. And I’m, like, “And you all think they’re the problem with this system?”

Carl Levin [the late Michigan senator and critic of financial-industry abuses] would describe the acronyms of finance as MEGOs: My Eyes Glaze Over. They were designed to confuse people and to make it seem mysterious.

And [to make you think] that you need them. Like, “I can’t understand this unless I pay someone fifteen per cent.” No. It’s a shill. You don’t need them.

What do you think you learned about politics from the fact that you went from one-per-cent favorability to winning? Is it the strange alchemy that you can’t predict? What is the takeaway on electoral politics that you didn’t know at the outset?

I remember, early in the race, the summer of 2021, we had an event. It was ninety-five degrees outside, and they invited all the people running for governor, which was twelve. And you had the former head of the D.N.C. and various elected officials. And we all showed up to give our pitch, and they’re all out there in ties and all this kind of stuff. And I showed up in shorts and a polo. And it created a bit of a stir, and people were, like, “He’s not taking it seriously,” and “It’s a vanity run.” I remember getting a phone call later on that night from the speaker of the house of Maryland, Adrienne Jones, and she said, “Have you heard the scuttlebutt?” I said, “Yes, Ma’am, I heard it.” And she said, “I just have one piece of advice: do not spend a second trying to be like them. Make them try to be like you.” She said, “If you do that, you might actually have a shot at winning this thing.” I was never going to keep up with them playing their game. I couldn’t.

What did that mean, to do your own thing?

I was going to places where there were not many Democratic voters. And you had the people who had all the consultants, and everyone else, who were, like, “You really need to spend time in four counties in Maryland, because that’s where the mass of the Democratic voters are.” So, “What are you doing out in Cecil County? Why are you going to Carroll County right now?”

What was your answer to that question?

They were, like, “There’s not a lot of Democrats.” And I said, “Yeah, but there’s a lot of Marylanders, and I plan on being their governor, too.” We also decided to take a different type of approach when it came to team-building. I remember when I was going through the process of picking a running mate—[Lieutenant Governor] Aruna Miller is the first immigrant ever elected to statewide office in Maryland. We’re the only ticket in the history of this country that is two people of color as governor and lieutenant governor. In the history of the country!

Once again, the conventional wisdom told me who I needed to select as my running mate. “You’ve got to pick this person from this part of the state, and dah-dah-dah.” And I was, like, “O.K., I hear everyone’s advice,” and I decided to go with the immigrant who came to this country from India and who was a former delegate. It was the absolute right decision for me, and I think the right decision for the state. The people who are closest to the challenge are the ones who are closest to the solutions. They’re just hardly ever at the table.

Did people try to tell you not to do it in the beginning? “This isn’t the right time.”

Oh, yeah. “What else do you want? Maybe you’re doing it so if it doesn’t work out, you can run for Congress?” And I’m, like, “You-all don’t get this. And you have no idea why I’m even doing this.” Because this is not about getting into politics. I was perfectly fine being Wes Moore before this. But I never tried to lose focus on the fact that, if I was going to win this thing, it was not because the establishment put me in. It was because the people did. So stay close to the people, because they’re not going to steer you wrong.

Now you’ve created a service program here in Maryland. As a country, we’re tugged between these competing impulses to want to serve and to be as self-enriching as possible. But keeping those impulses in some balance is essential. I think people would say, “Why are you paying so much attention to service?” Does it have anything more to it than giving kids out of high school something to do for a year? How do you see the larger implications?

Service has to be the way that we define and analyze our contribution to the world. And that’s why there are a few components that I wanted to be very clear about. One, this is a service-year option. We’re not telling people that it’s mandated. When students graduate from high school, they can join the military, go get a job, go to four-year school, go to trade school. Well, in the state of Maryland, they now have another option. And that’s to do a year of service.

The second piece is that we aren’t going to tell you how to serve. If you want to serve in the environment, work with veterans, support older adults, or help to build homes, it’s completely your choice. We’re not trying to tell you what should make your heart beat a little bit faster. That’s a personal decision. But the thing that I do know is you should have the opportunity to do that. And the long-term benefit—not just to the individual, as I saw in my life, but the long-term benefit to society—pays dividends. Service is sticky, and service will save us—especially at this time, when you have this political vitriol, and people seem to care more about where the idea came from than if it is a good idea. There’s something so dangerous about that, and so tribal. We’ve got to get to know each other again. And one of the best ways of getting to know each other again is to ask people to serve together.

The resistance that you usually run into, from the right, would be “We don’t want mandates.”

“Socialism.”

Yeah. But there are some Republicans who are interested. Is there an opportunity for a larger program based on what Maryland is doing at this point?

A hundred per cent. We introduced ten bills in this legislative session, and we didn’t just go ten for ten; we went ten for ten and bipartisan on all of them. So the service bill got Democratic and Republican votes. I think that Maryland is going to be the first state in the country to be able to have a service-year option. Maryland will not be the last.

I read the speech you gave at Morehouse, in which you said that the effort to rewrite history reflects a fear of “people understanding their power.” That ties into this question of unity. You’re worried about “a deep rot that threatens to hollow out our future by eliminating our past,” whether it’s a history of attacks on Jews or Asian Americans and others. Do you sense that things are potentially going to get worse before they get better? How are you feeling right now about where we are on unity and disunity?

I think this is a moment for our society to say to those who think that [creating disunity] is a smart political strategy, “You’re not going to win.” Because it’s clear that, for a lot of the people who are peddling this, it is not thoughtful. It’s political. They’re doing it because they think this creates a political window for them. I don’t think they actually really believe much of the stuff they’re saying.

So the possibility of preventing more reliance on right-wing political wedge issues is proving that it’s not good politics?

The thing we have to show is that there are consequences. If you are the governor of a state who wants to make part of your platform, and part of your accomplishments, the fact that you do things like restrict women’s access to abortion care, or if you have said, “Well, people should not be able to read ‘The Bluest Eye’ or ‘Beloved,’ or a book about Roberto Clemente or Hank Aaron,” then there should be consequences to that. And when I say consequences, it should not just be that you are defining your own political failure. I want there to be economic consequences. I want people who are doing business in that state to stop. I want teachers who are teaching in that state to come to Maryland.

This is going to be a state that is going to be welcoming to people. It’s going to be welcoming to businesses. It’s going to be welcoming to entrepreneurs. It’s going to be welcoming to our educators. It’s going to be welcoming to people who want to be seen and identified in their own society and in their own skin. And I want them to build here. So, yeah, for people who want to push that ideology, I don’t just want them to lose politically. I want them to lose financially—and I want Maryland to be the beneficiary of it.

Even before you took office, Politico had a story headlined “Wes Moore Has Never Been Elected to Anything. Some Backers Are Already Eyeing the White House.” How do you experience that level of expectation and pressure?

I don’t. I really don’t. Honestly, I’m not a political animal, you know what I’m saying? I didn’t come through a system. I was not the establishment’s first choice when I decided to run for governor. I’m only decades away from being in the back of a police car with handcuffs on my wrists. When people said, “Well, what made you want to get into politics?,” I said, “I didn’t. I wanted to be governor,” because I know the uniqueness of this role. I know the issues that I was working on before becoming governor, and I know the power that a governor has to be able to actually address this stuff. I’ve been pushing to get adjustments made to the child tax credit for years—literally years—because I know the impact that it has on child poverty. And oftentimes I’d find myself banging my head against the wall, because elected officials, if it’s not in their best interest to attack child poverty, they go do what they want to do.

I said, when I ran for office, that we were going to have the most full-frontal bipartisan attack on child poverty the state has ever seen. And one of the first bills we got passed was the Family Prosperity Act, which made permanent the child tax credit in the state of Maryland. So, weeks into the job, I was able to do something that I was working on for years. So my honest answer when people say, “How do you think about your political future?”—my answer is I don’t, because I’m having a lot of fun doing the work we’re doing right now. ♦