The Baltimore sun seems to shine brighter on the 400 block of North Howard Street. On any given weekend you can follow the sound of laughter and sizzling vegan burgers to arrive at “Healthy Howard Row” – a cohort of Black-owned businesses restoring the energy of the block by creating a community around wellness and cultural conversations. The cultural impact of Healthy Howard Row businesses – Cuples Tea House, Vinyl & Pages, Vegan Juiceology, a Women’s Wellness Lounge, and the cherry on top, Cajou Creamery – is a force to be reckoned with in the bright future of Baltimore City.

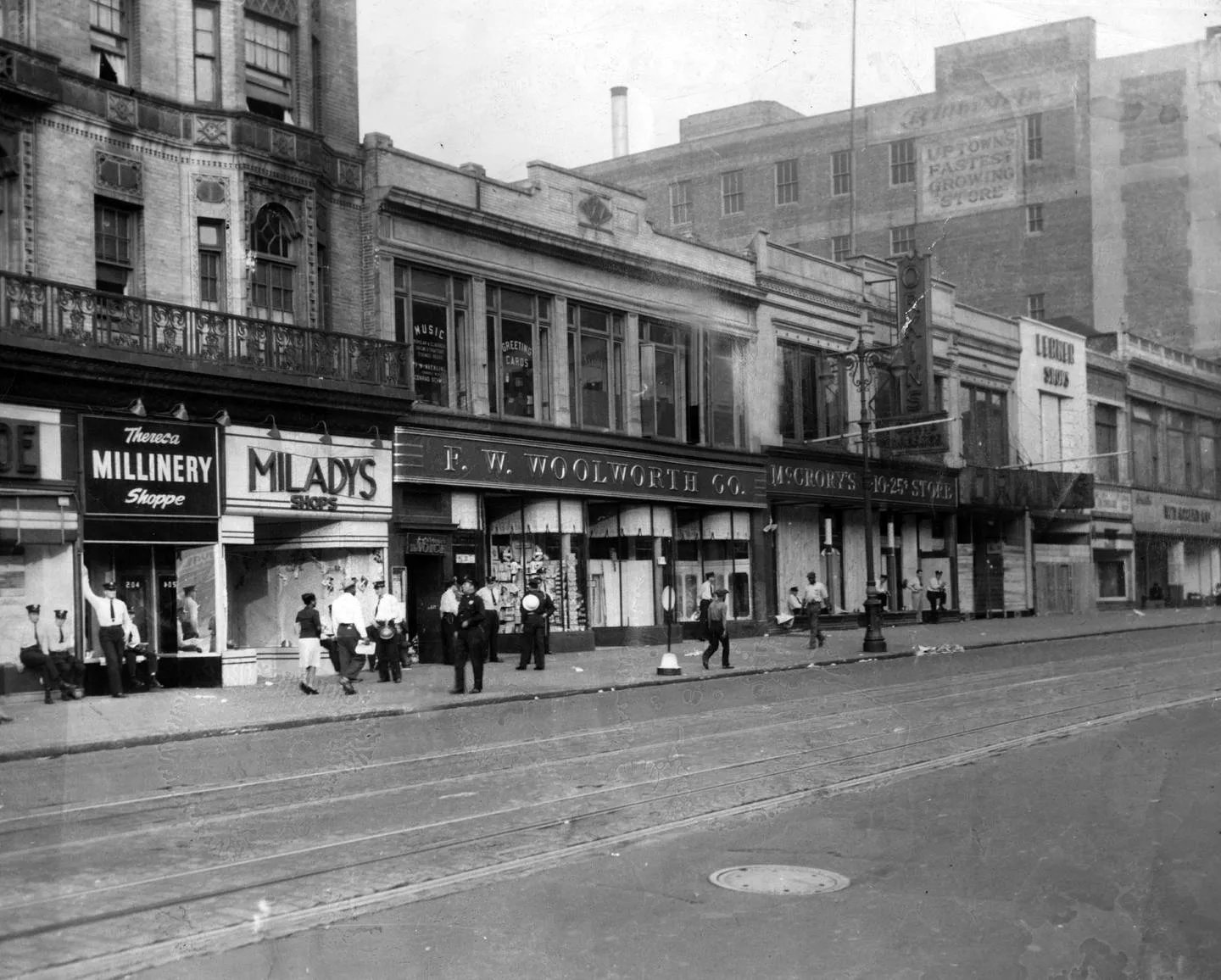

Howard Street is a central artery of Baltimore, connecting museums, universities, hospitals and my personal favorite, the Eubie Blake Cultural Center, along its 2.5 mile run from north to south. In the early 19th century, its downtown blocks were bustling commercial centers home to famed department stores like Hutzler’s, Hecht’s and Hoschild’s; the proud and persevering Lexington Market; and plenty of jewelry, antiques and performance venues to draw in passersby. As the department stores began to shutter their doors in the 1950s, the entire region began to decline, with commercial development in the Inner Harbor and Fells Point snatching businesses out of the Howard corridor. Since the 70s, these historic buildings with stunning Victorian facades have remained largely vacant and deteriorating.

Just beyond the shadow of a ghost town, Black joy and wellness fill Howard Street with sweet dreams of community healing. Hearing the hopes shared by Healthy Howard Row business and community leaders, it’s easy to believe that the recent revitalization of the neighborhood as the Bromo Arts District — replete with new shops and art spaces — will stick around.

Dwight Campbell, the chef and co-owner of plant-based ice cream shop Cajou Creamery, has no plans to leave Howard Row. Dwight has run the creamery with his wife, Nicole Foster since 2017 although their Howard Row location opened in 2020.

“We opened our doors in the middle of the pandemic and flourished because people were locked down at home,” he says. “They wanted comfort food.” Dwight was first inspired to create ice creams with a raw cashew milk base to help manage their two sons’ lactose intolerance and would send homemade pints along with them to birthday parties. The pints became so popular that orders began to pile up, and Nicole seized the opportunity – she brought home a business license for Cajou Creamery. Five years and one pandemic later, Cajou Creamery is thriving, in-stores at Whole Foods from New Hampshire to South Carolina, and on the brink of opening a second location in Baltimore’s Hollins Market. Dwight remarks that Baltimore has shown them unconditional love since they moved here from DC in 2018.

“And eventually one of the buyers at Whole Foods heard about us on a podcast, No Pix After Dark… Harbor East had a black female store manager and the assistant buyer was an African American gentleman and they pushed us, they pushed us to every Whole Foods that they could get us into.”

Ice cream convos with Cajou Creamery

I spent the day with Dwight saying “Yes, chef!” and “Is that supposed to be boiling, chef?” as he tested a new recipe for a Black Joy-themed ice cream flavor, Dreams of Dakar. We spoke of his time as a sous chef in the National Gallery of Art, his upbringing in Jamaica, and of course, how Cajou’s menu came to be.

MF: I think when we first met you said [Baltimore’s] a very cooperative place. And I’m wondering, could you talk a bit about this block here?

DC: The director of Bromo Arts District Market Center, which is the main street organization for this area, was also a customer. And she said, ‘We’re gonna be doing a storefront competition and I would love for you guys to enter.’ There was several, probably dozens of applicants and us and Cuples Tea won. We both got these built as locations, a year of free rent which was, for a small business, huge. That’s like somebody handing you a bag of money and saying — go. And the people, they’ve come, they’ve supported.

This space is not just about selling ice cream. It’s about conversations. There’s many connections that have been made here, many deals that have been made within these walls through different parties. I tell people, just come hang out. You never know who you’re gonna meet. One day you come and you may be sitting down next to a senator.

So Cajou is, in a sense, a community catalyst for conversation. In Black families that’s the kitchen. No matter how big the party is everybody ends up in the kitchen. And there’s a bunch of conversations going on in the kitchen ‘til either mama or grandma says, ‘Get out, I can’t think!’ It’s something that happens throughout our culture whether you’re from Nigeria or you’re from Trinidad, everybody ends up in the kitchen. So, this is our big kitchen.

MF: I love that. We’ve been watching a lot of really powerful activism happening in ice cream shops across the country and I wanted to get your perspective as an ice cream shop in Baltimore. I think you sort of spoke to this a bit with the kitchen being a community space. But how do you see ice cream shops collaborating with community and what does that look like for Cajou? Or, what’s the overall relationship between ice cream and community building?

DC: That’s real easy for me because having two kids and wanting to educate them on the real world, this ice cream shop is a perfect catalyst for intergenerational conversations. Conversations about generational wealth, conversations about moral accountability for our actions in who we are as people and how we engage in community. When you walk down this block people notice the fact that there’s a cohesiveness to the block, even though all the businesses, everybody’s from all parts of the Black community. But this is somewhere where it’s cohesive because we have the same principles of how we should do business and engage in the community.

MF: You are, as you may know, part of a long tradition of visionary black ice cream makers. James Hemmings, Alfred Cralle, Augustus Jackson. What does it mean to you to be a part of that legacy?

DC: First, I’m humbled by that. And two, ice cream was never something that was in my perspective or my view of what my future would be. I expected to move from sous chef to executive chef and get an executive chef position in a restaurant or end up opening my own restaurant or something like that.

Being the product of two strong black women, my stepmother and my mother, I was always taught to think outside the box and see the gifts that are given to you that you might not at first see as a gift. But they are. Because if you’re able to do something to have an impact, it’s like Maya Angelou says, you can tell people a whole bunch of stuff and they’ll forget it. But how you make them feel is how they remember you. They feel the energy and the love if that’s what you show them.

So, ice cream was something that showed me as a chef I like to see when people take a bite and those eyebrows go up. Their jaw drops and they scramble to take the next bite. You know, to see a little boy or girl with skepticism on their face because they’re used to dairy ice cream. Then they come and they’re like, ‘I want that one, I want that!’ – and to see the excitement. That gives me joy. That gives me a sense of fulfillment.

MF: Well, that was my last question, what memories of ice cream bring you joy? But I feel like you’re doing it, you’re living it. You’re living it every day.

DC: Yeah. And that’s funny because ice cream was never in my childhood. I mean, I have very sensitive teeth, so I never ate ice cream a lot. But I grew up churning ice cream as a kid. It’s a melancholy memory because as a kid you love the ice cream, but you hated having to churn it.

MF: How long were you churning?

DC: Four hours. Four hours was minimum. And you and your brothers take turns. And you go for 20 minutes, and somebody switches in. You go for another 20 until it’s done. I think about it now [and] I didn’t mind doing it because it gave my brother and sister, and everybody else who had it, joy. And seeing them, and even me, I would taste it and like it and enjoy it. So, I guess subconsciously I kind of tapped into that.

MF: Asè, thank you. Where can we tap in with Cajou?

DC: Well, Cajou is going to our first out of state festival in July. We’re going to Vegandale in Randall’s Island in Brooklyn. It’s like 40-50,000 people. That’s our first out-of-state thing. We’re opening our second location in Hollins Market area. It’s gonna be bigger. We’re gonna have an outdoor patio. We’re gonna have more seating on the inside. We’re gonna have more food items.

And, you know, just support…we’re trying to make it as non-extractive as possible so we can raise the money to do that through our revenue instead of having to go to a lender and then paying them back. And we don’t want to have to pass anything on to our consumers, which is what we always have done from when we first launched this. I think it took four or five years before we even had the first price raise of our product. So yeah, being non extractive is the best thing for us as a brand.

We will probably at some point within the next year be launching a Kickstarter. And we started kind of doing the beta testing of food items here. We started brunch on the weekends. We do 12pm to 3pm, open faced avocado toast and beet hummus toast. I like to pickle stuff. Jalapenos, onions. You know, all of it. So, we’re trying to do everything step by step and try to do it well so that we don’t make mistakes, because eventually those mistakes are gonna cost us and cost our customer base. We’re trying to do it as nice and easy as possible.

This small excerpt from our conversation gives you a taste of where the new Black Joy flavor comes from — a non-extractive, wellness-centered culture that folds in the multitudes of experiences and ingredients of the African Diaspora. It also gives you a sense of the careful progression of the Bromo Arts District toward a lively cultural hub where Baltimoreans of all walks of life can connect, eat and laugh together.

If you get a chance, take a Saturday afternoon to bask in the glow of Howard Row and find you something sweet. The power of Black joy will be there, waiting for you to claim it.

Reserve your pint today!

Can’t wait to order our mango-lime vegan ice cream with a sorrel reduction? Dreams of Dakar is a collaboration with Cajou Creamery to help to sustain the energy that is building on Howard Row – sign up for our waitlist to be the first to get your scoop on National Ice Cream Day, July 17th.