Earlier this month, the Alabama Medical Cannabis Commission awarded eight licenses to companies that qualified as majority owned by a member of a minority group — defined as individuals of African American, Native American, Hispanic, or Asian descent, according to the commission’s spokesperson.

That’s two more than were awarded licenses by the commission on June 12. All licenses issued on that date, however, were put on hold four days later when the AMCC revealed inconsistencies in the tabulation of scores used to rank applicants. Those licenses were never issued; the commission said the scores were rectified before the most recent meeting.

Among 90 applicants, 24 companies were awarded licenses on August 10 to do business in the state as cultivators, processors, transporters, dispensaries, and a testing lab.

According to the 2021 state law making it legal to grow and distribute medical marijuana in Alabama, at least a quarter of the awardees in all but one category (integrated facility) had to be at least 51% minority-owned.

The eight minority companies with licenses are (applications—most heavily redacted—are linked):

TheraTrue Alabama, LLC (integrated facility, which can cultivate, process, transport, and dispense medical cannabis and can have up to five dispensaries) Southeast Cannabis Company, LLC (integrated facility), I AM FARMS (cultivator) 1819 Labs (processor), Enchanted Green (processor), Statewide Property Holdings AL, LLC (dispensary), and International Communication, LLC (secure transporter), XLCR Inc. (secure transporter).

I AM FARMS and XLCR were not among the firms awarded licenses in June.

To confirm their minority ownership status, according to commission spokesperson Brittany Peters: “Applicants were required to provide documents to demonstrate that the applicant is at least 51% owned and controlled by a member of members of a minority group. Applicants could provide documents such as birth certificates, military records or other government-issued documents that includes race.”

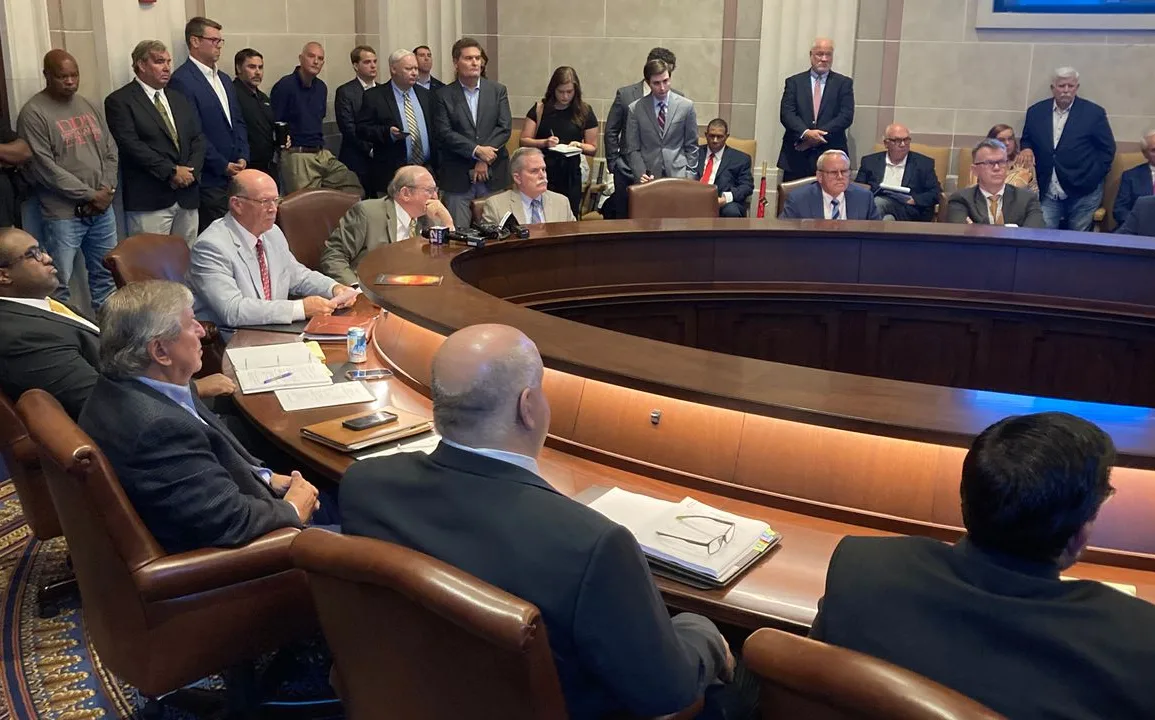

The newest round of licenses, though, is also currently paused. On Thursday Montgomery County Circuit Judge James Anderson said he will place a temporary hold on the issuance of licenses after hearing lawyers representing companies denied a license argue that the commission violated the Open Meetings Act by filling out forms with their nominees for licenses in each of the categories.

The Open Meetings Act allows public boards to close their meetings for certain purposes but not to vote or take official action during closed, executive sessions.

While the commission did not vote on the nominees until reconvening, applicants not on any lists weren’t considered during the open portion of the meeting.

Speaking before the judge, Wallace Mills, an attorney for Specialty Medical Products of Alabama, said the nominations were, for all purposes, votes because they eliminated applicants.

“We can call it a nomination if we want to,” Mills said. “But we routinely nominate people by vote. That was a vote.”

A hearing on the alleged violation is scheduled for August 28.

Antoine Mordecai Sr., CEO of Native Black Cultivation, which has been growing hemp at its Jefferson County facility since 2020, said it was “disheartening” to be denied a license a second time.

“However, I am still proud of my peers that were awarded licenses,” he said. “I understand the amount of work it took to get everything submitted and approved. It was not an easy task. It’s great for Alabama to have a program that is here for the people. I’m confident awardees will do their best to provide quality products for the citizens of Alabama. “As for Native Black Cultivation. We plan to challenge the process and offer clarity on our deficiency to the commission so that we can be awarded a license.”

TheraTrue, according to its website, is “majority black-owned and our board and management team are majority people of color.” Dr. Paul Judge, an inventor and entrepreneur, is listed as founder/chairman; Victor Mancebo is CEO/Board director. Both are African American.

Minority participation in what is projected to be a $70 billion industry by 2028—and last year accounted for 428,059 full-time jobs, according to the 2022 Leafly Jobs Report—has been a source of frustration nationwide since California became the first state to legalize marijuana in 1996.

African American entrepreneurs account for less than two percent of business owners in the nation, according to the 2021 Leafly Jobs Report. That’s worse than in 2017 when 4.3% were Black. (That year 81% of cannabis business owners were white, 5.7% Hispanic, and 2.4% Asian.)

“The cannabis industry must show true commitment to equity as it expands, so the wealth generated by this new opportunity will uplift minority communities,” the 2021 reports stated. “If it cannot we will continue to see these communities struggle in the shadow of white supremacy without a fair shot.”

Gummies, tablets, capsules, tinctures, patches, oils, and other forms of products are allowed by the legislation. They can be used to treat myriad conditions, including chronic pain, the physical effects of cancer, depression, panic disorder, epilepsy, PTSD, and others.

Patients must receive a medical cannabis card from a doctor to be able to buy the products at licensed dispensaries.

Thirty-nine states, including Alabama, have approved the production and use of medical marijuana, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.