Michael Arnold’s parents bought his childhood home in Ann Arbor’s Water Hill neighborhood in March 1950 on a $4,000 land contract, just months before he was born. Arnold, who is Black, recalls his vibrant neighborhood being almost all Black when he was growing up. But today, he says, “many Black families can only look at the outside of the houses from the sidewalks.”

“There’s no way I could afford to live in my old neighborhood today,” he says. “I’ve even had to leave the city altogether.”

Arnold, 73, now lives in Brighton. There he met financial planner Andre Watson, who is taking a major role in developing a plan for Washtenaw County to make amends for the many ways it’s harmed Black residents like Arnold. Watson is the chair of the Washtenaw County Advisory Council on Reparations. Constituted last February, the Council on Reparations will summarize the specific ways that county policies and practices have historically, and continually, harmed the lives of Black people. Members will be assigned to represent various sectors, such as housing and real estate, post-secondary education, and the criminal legal system.

“There is a pain here caused by racism and racist policies from a long time ago. That pain still exists today,” Watson says. “If you really, really talk to people and poke around behind the curtain you’d be surprised. There are still families experiencing spiraling poverty as a result.”

“Charged and challenging” conversations

Watson says that when people walk through Arnold’s old neighborhood in Ann Arbor, all they might see are big, beautiful homes.

“But, for many African-Americans, it can be a bit traumatic,” he says. “They see a neighborhood that they’ve lost, or a neighborhood they feel they can’t ever have again.”

That’s true of many widely celebrated features of Washtenaw County, which have long been difficult or impossible for residents of color to access. Pointing to other trailblazing municipalities across the country doing similar work – such as Detroit and Evanston, Ill. – Washtenaw County Racial Equity Officer Alize Asberry Payne says conversations about reparations can be “charged and challenging.”

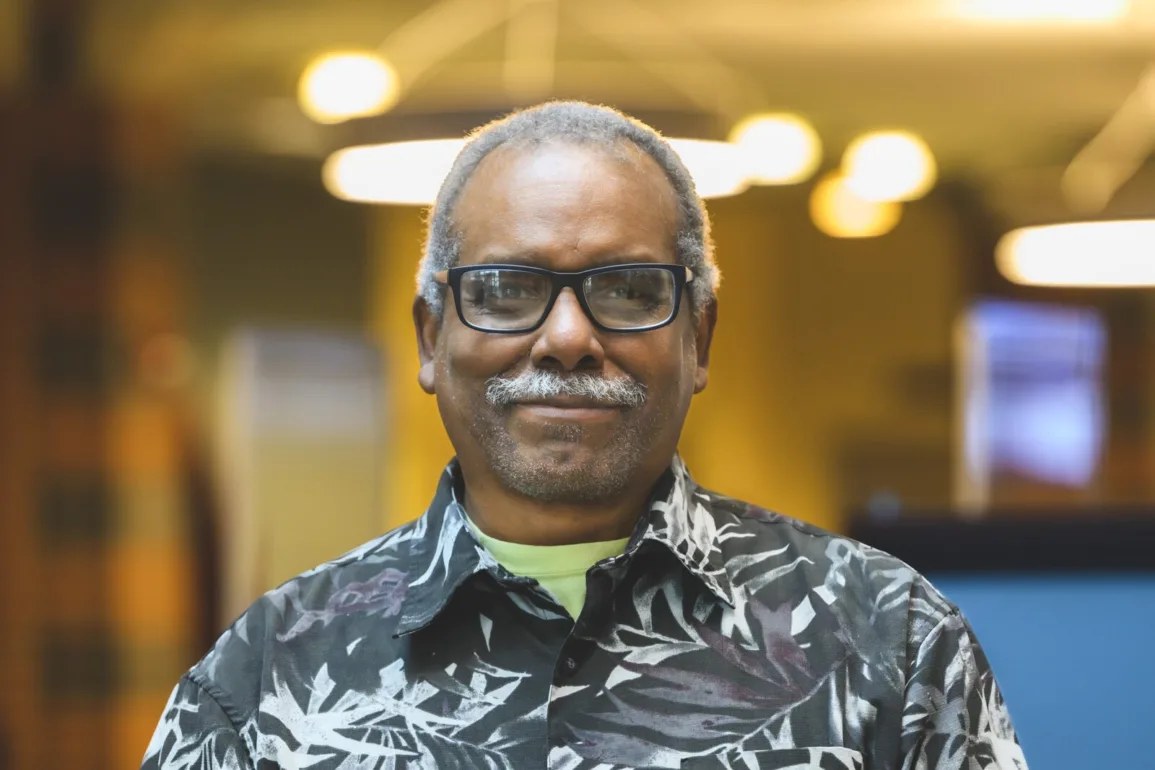

Washtenaw County Advisory Council on Reparations chair Andre Watson.

Washtenaw County Advisory Council on Reparations chair Andre Watson.

“Locally, we have to reckon with some things that are understandably hard to look at,” she says.

For instance, despite being unenforceable, there are still examples of racially restrictive covenants listed on the deed contracts for homes in certain areas of Ann Arbor. These covenants state that these properties cannot be owned by people of color.

“That directly impacted some families’ ability to create and sustain wealth, because for many American families, homeownership has been a path of economic and social mobility,” Asberry Payne explains. “It’s a part of our local history, and the effects are still being seen today.”

Washtenaw County Racial Equity Officer Alize Asberry Payne.

Washtenaw County Racial Equity Officer Alize Asberry Payne.

The council on reparations began after several years of work by Asberry Payne’s office’s Exploratory Committee on Reparations. That committee came to exist in the equity office as a direct result of data showing stark racial disparities in the early impacts of COVID-19 in Ypsilanti.

“We started seeing secondary impacts really quickly, things that were not explicitly health impacts,” Asberry Payne says. “The further back we went, the more strings we pulled on, it became apparent that we were looking at issues driven by the racial wealth gap, long-term housing discrimination, disparate policy, long-term education and achievement gaps.”

“Another reason to be proud”

For reparations council member Hazelette Crosby-Robinson, the county’s move toward reparations is “another reason to be proud” of her community. Crosby-Robinson, who worked for Washtenaw Community Mental Health for 25 years before retiring, was chosen to represent the health sector.

“It’s a known fact that the people in the eastern side of the county are less represented and have not been treated fairly and equitably,” Crosby-Robinson says. “That we’re willing to look back generations and examine the equitable distribution of resources throughout the county says a lot about our integrity.”

Crosby-Robinson, who is Black, was born and raised in Ann Arbor. However, when it came time for her to pay for her own apartment she chose to leave the city she loved behind. She moved to Atlanta for a while because it was affordable, unlike Ann Arbor.

“People and families are still being pushed out today,” she says. “I’m hoping we can get to the bottom of longstanding inequities. Then we can submit a plan that dollars can be attached to.”

Washtenaw County Exploratory Committee on Reparations council member Hazelette Crosby-Robinson.

Washtenaw County Exploratory Committee on Reparations council member Hazelette Crosby-Robinson.

Reparations, whether in the form of money, formal apologies, or legal changes, can make a meaningful – and sometimes immediate – impact, says Gregg Barak, an emeritus professor of criminology and criminal justice at Eastern Michigan University (EMU). When he applied to the reparations council, he was tapped to represent the post-secondary education sector. This past November, Barak resigned from the council for personal reasons, but he remains passionate about the importance of reparations work.

“We need to reimagine institutions that cause racial violence in our communities,” he says. “We need to reimagine the way they work and function and the way in which money is allocated to those institutions.”

Barak, who is white and grew up in Los Angeles, came to Ann Arbor as a department head of sociology anthropology and criminology at Eastern Michigan University in 1991. Two years prior to coming to EMU, while he was a department chair at Alabama State University, Barak developed and established the first Master of Arts and Master of Science degrees in criminology at a historically Black college and university. He says that America overspends on the criminal justice system and on police, but underspends on policing white-collar and corporate crime.

“That’s where most of the theft occurs from Black communities, as when Wall Street imploded and people lost their homes,” he says. “It’s very real – people dying and getting hurt, and losing their livelihoods or never getting livelihoods. There are very concrete relationships.”

Moving forward

Asberry Payne is asking all interested community members to apply for positions on the council. She underscores that the council is still in a phase of formation and education.

“We’re making sure that there’s a solid structure for operations of the council as well as a solid framework for broad community engagement,” she says. “This is a huge community question and you have to move at the speed of community if you want a community-driven process.”

Andre Watson and Michael Arnold.

Andre Watson and Michael Arnold.

As the council members settle deeper into their roles, Watson, like Asberry Payne, is hopeful for growing community awareness and support.

“We need to have the courage to have challenging conversations in order to grow as a community,” he says. “We as a county pride ourselves as being forward-thinking, and work like this will test this.”

Jaishree Drepaul is a freelance writer and editor based in Ann Arbor. She can be reached at jaishreeedit@gmail.com.

All photos by Doug Coombe.