California’s groundbreaking Racial Justice Act (RJA) of 2020—recently made retroactive for those already incarcerated—goes beyond any other state or federal attempt to ensure equal treatment under the law for all races. It expands felony and misdemeanor criminal defendants’ ability to cite racially unequal treatment in their charging, convicting, or sentencing. And if the court rules that a violation has occurred, it must impose a remedy specified in the legislation, such as declaring a mistrial, reducing charges, or even vacating convictions or sentences.

This paradigm shift has prompted questions regarding courts’ capacity to adjudicate such claims. To begin with, how much racial inequality exists in the state’s criminal justice system? Is there enough available, reliable information to find out? Of the four types of claims possible, two hinge on bias experienced by the suspect and two are based on data that demonstrate inequitable treatment under the law. For the latter types, what do existing data sources provide to ensure claims can be resolved fairly and swiftly?

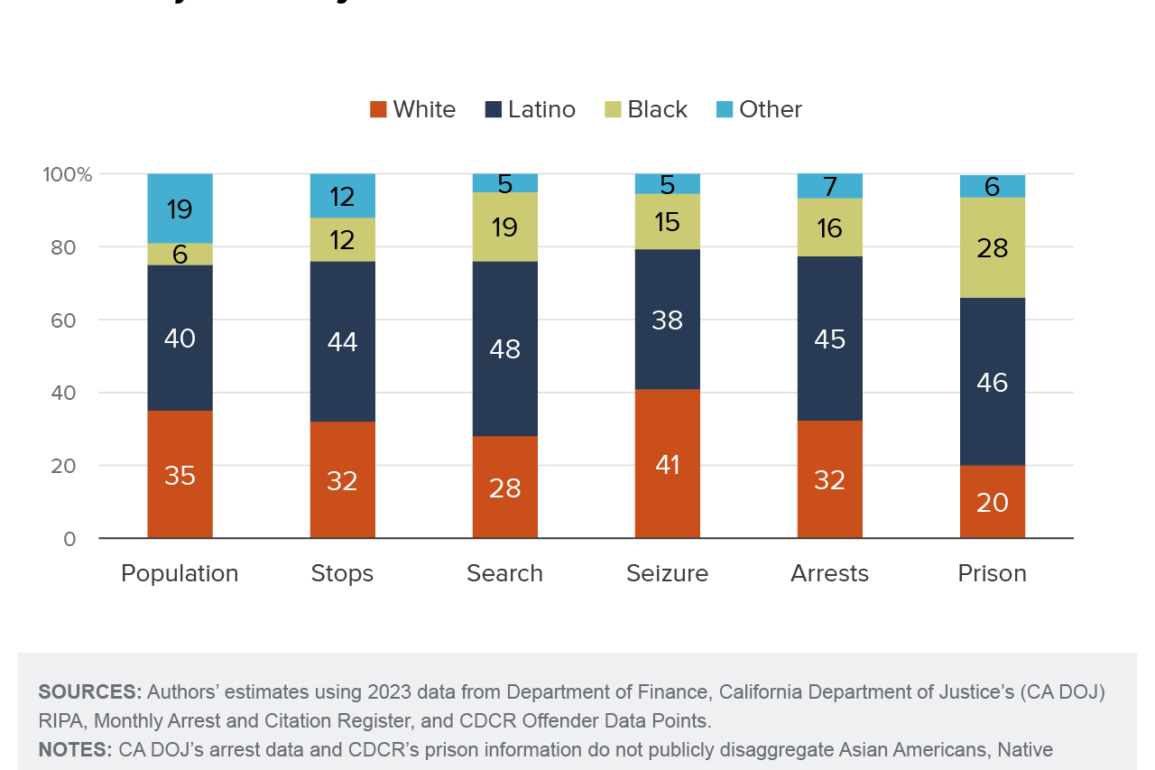

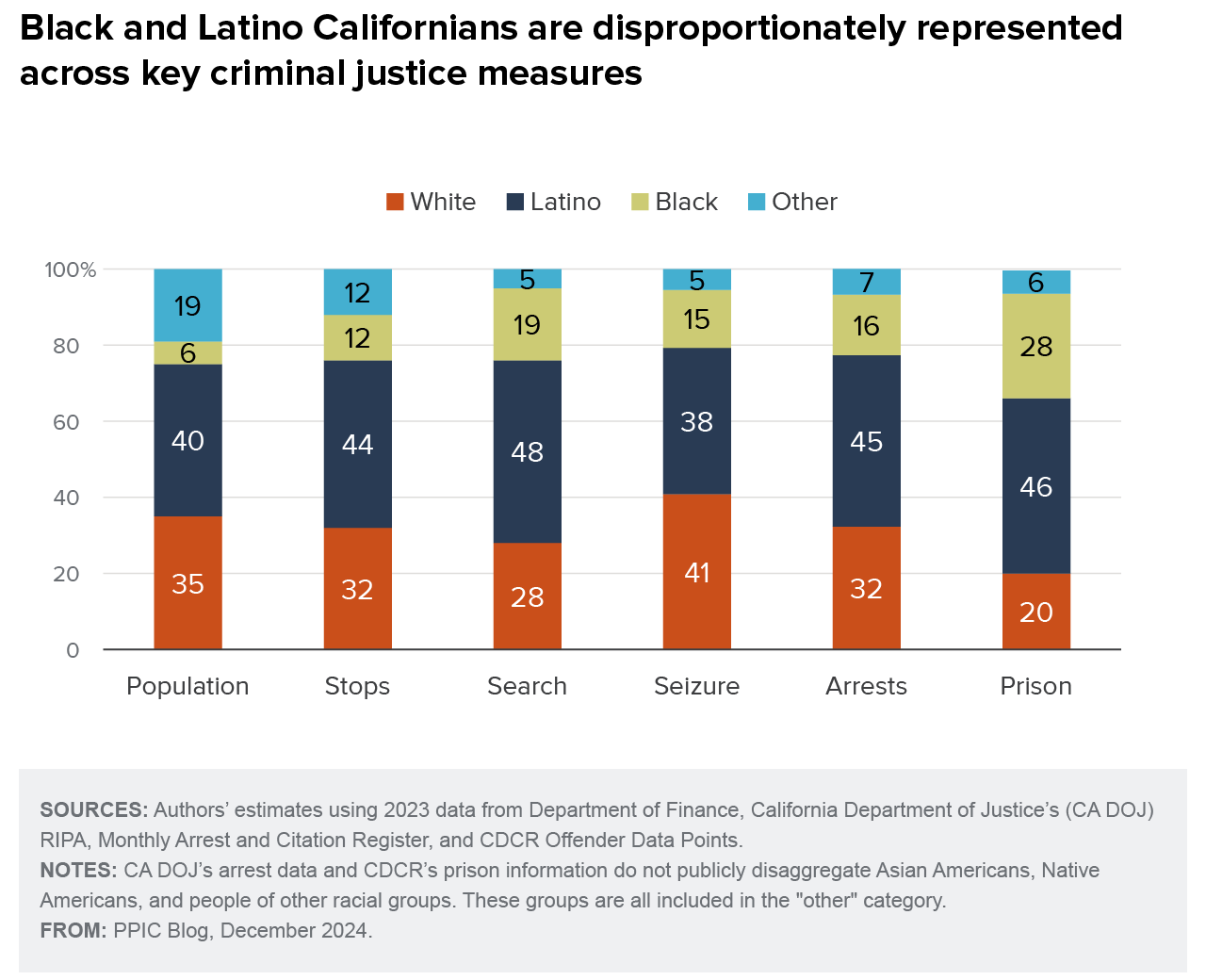

The good news is that improvements in data availability and transparency do give us some answers with respect to racial disparities in law enforcement stops, arrests, and prisons. The Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) of 2015 requires California law enforcement agencies to report perceived identity characteristics—including race/ethnicity—for each police stop. As the figure below demonstrates, this and other data—such as California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) prison population—are illuminating.

Even so, data-focused RJA claims may need more granular and integrated data than is available and/or easily accessible. They require a demonstration of unequal treatment between individuals in similar situations engaged in similar conduct in the same county. The courts are still determining what that means in practice. But successful cases—such as one challenging the application of gang sentencing enhancements—have already shown that any analysis will at least require county-specific information on race and offense.

Currently, court and prosecutorial data are collected separately. They are kept at the county level and normally not publicly available. To complicate matters, they do not typically contain detailed information on the law enforcement interaction, arrest, or prison sentence, and have no way to integrate datasets. Moreover, the California Board of State and Community Corrections does not provide race/ethnicity information in its publicly available jail population data. And for the public, neither CDCR or CA DOJ disaggregate beyond Black, Latino, and white.

Though the courts are still determining the scope of RJA claims, one thing is patently clear. More accessible, reliable, and integrated data will be pivotal to correcting any systemic disparities across California’s criminal justice system. Various tools and resources are currently available, but a more uniform system may prove critical. To that end, the 2022 Justice DATA bill requires local and state prosecutors to report case information to the CA DOJ. However, it has not yet received the requisite funding for full implementation. If it does receive full funding, data collection would begin in 2027.

Even though California does not yet have a standard statewide dataset available to all stakeholders, the work toward equity in criminal justice is progressing. For example, a RIPA Board comprising police practitioners and researchers annually assess whether racial disparities during law enforcement stops are being reduced. It also provides recommendations on how to mitigate them. Going forward, this model may serve as a helpful framework for creating an integrated system that facilitates efforts to comply with RJA.