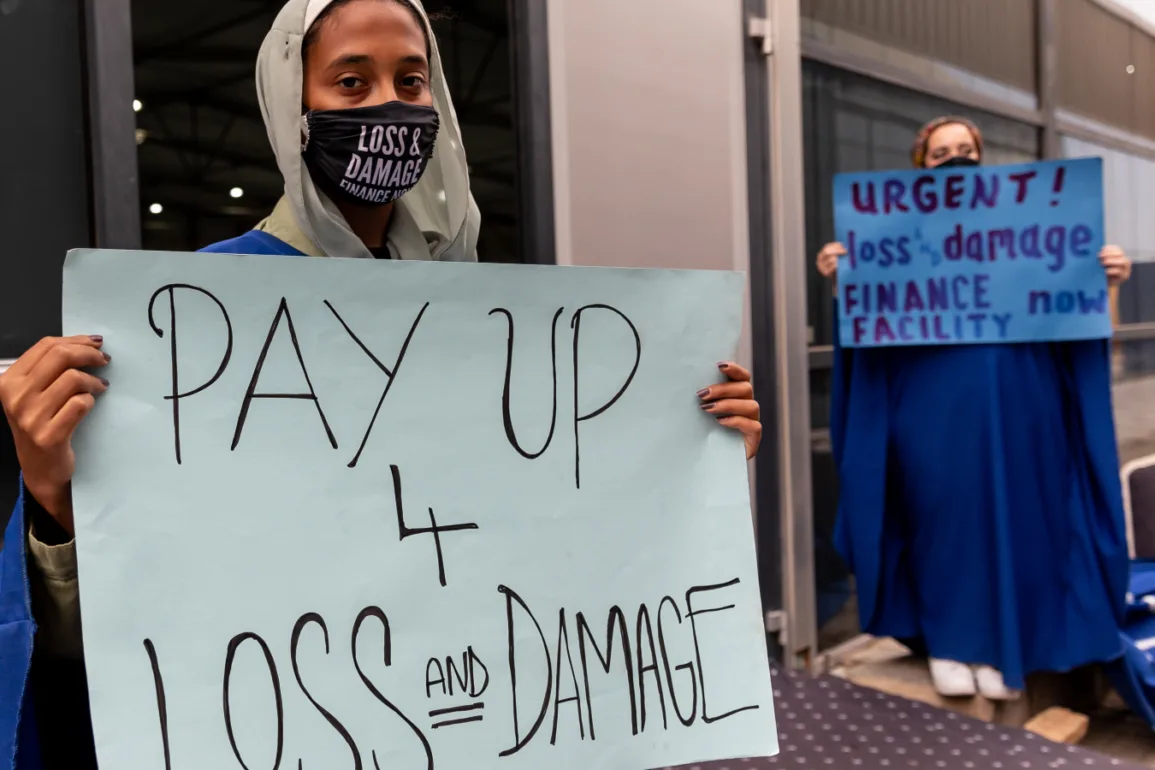

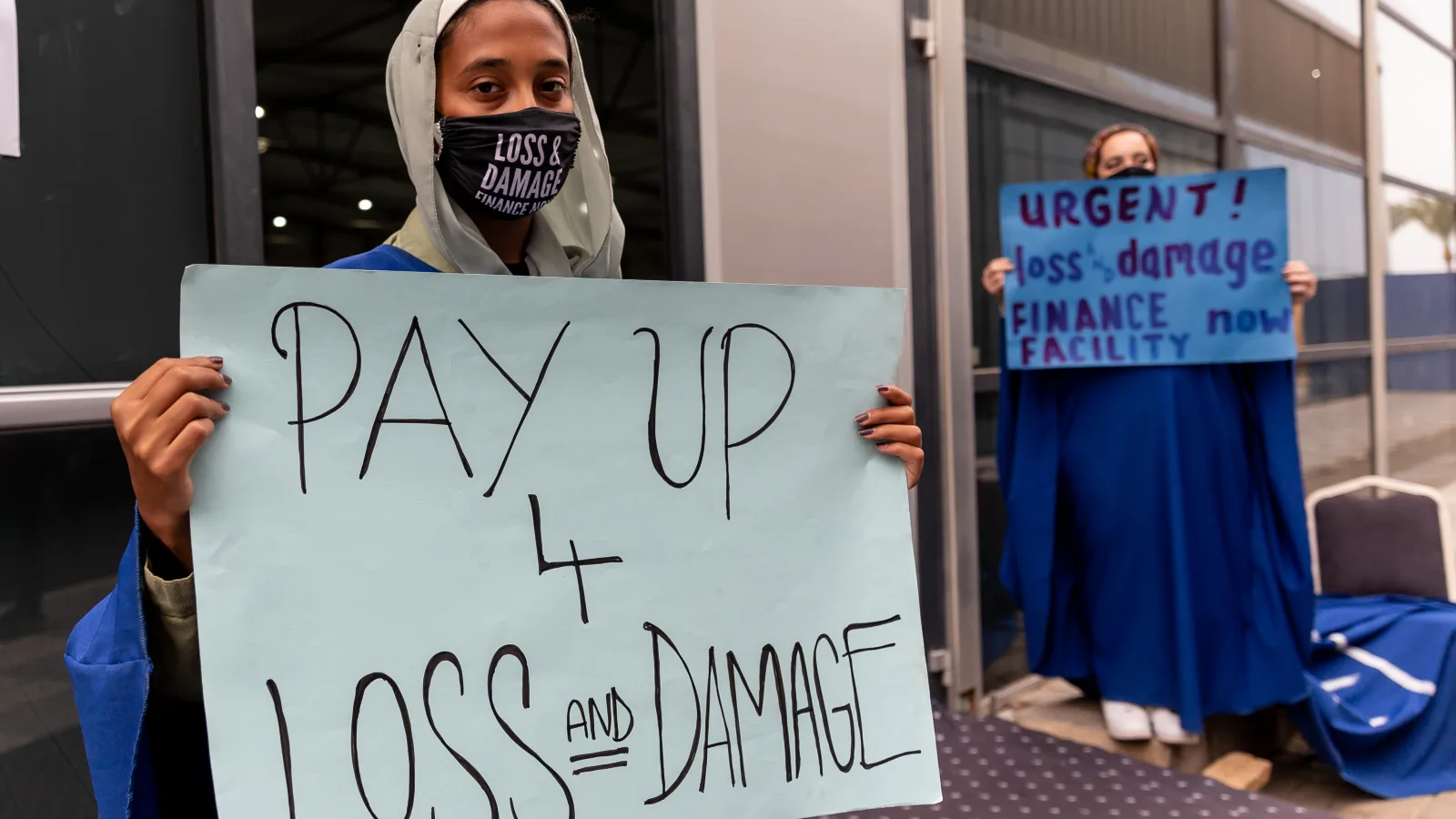

At the United Nations’ annual climate change conference in Egypt last year, bleary-eyed negotiators reached a long-sought consensus on the push to pay out reparations for the damage caused by climate change. For the first time, the world’s countries formally recognized that developing countries, largely in the Global South, disproportionately suffer from the effects of climate change, and they agreed to establish a “loss and damage” fund to compensate for those harms.

While the agreement was historic, essential and controversial features of the new fund — who will pay into it, who will receive payments from it, and how it will be administered — were left to be decided by a committee made up of representatives from both developed and developing countries.

While there was hope for progress on these decisions by the time of the next UN climate conference, which goes by the name COP28 and will begin in Dubai next month, the transitional committee now appears deadlocked over a number of critical issues — in particular over whether or not to house the loss and damage fund in the World Bank. Proponents of that move, particularly the U.S. and European Union, see it as a natural fit with the international financial institution’s mandate, which since its 1944 founding, has been to support economic development in emerging economies. The World Bank only added climate change to that mandate earlier this year. Now, its stated goal is to “create a world free from poverty on a livable planet.”

But developing countries that stand to benefit from the fund say that the World Bank has cumbersome rules in place that would make it a slow and ineffective fund manager and could also limit which developing countries can draw from the fund. They also fear that a World Bank fund is likely to favor paying out loans, which will need to be repaid, over the grant-style funding that would be more in keeping with original visions for the fund. Decision-making power at the World Bank is skewed toward the U.S. and the European Union — indeed, the U.S. has had outsized influence in selecting the bank’s president — and developing nations have been calling for its reform.

“The push for the World Bank’s involvement as a host of the loss and damage fund — an entity notorious for exacerbating crises and perpetuating global inequality — is starkly inappropriate,” said Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at the environmental organization Climate Action Network International and a longtime observer of climate negotiations, in a statement. “Wealthy nations must confront their longstanding inaction and acknowledge their significant role in the current climate crisis.”

Carl Hanlon, a spokesperson from the World Bank, told Grist in an email that the organization and its representatives are “supporting the process and are committed to working with countries once they agree on how to structure the loss & damage fund. We are not a party to the process, but we are prepared to help in any way we can.”

The discussions have been taking place this week, at the committee’s fourth and final meeting ahead of COP28. The committee is expected to release a set of recommendations that will form the basis of further negotiations over the loss and damage fund at COP28. With the recent deadlock, its ability to do so is now in doubt.

The world has already warmed an average of 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) globally since pre-industrial times. The loss and damage stemming from the effects of this warming — more intense storms, prolonged droughts, unprecedented flooding — are disproportionately felt by the world’s poor in developing countries. For this reason, loss and damage formed one of the pillars of the 2016 Paris Agreement, when the world’s countries agreed to take efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The other two pillars are mitigation, which refers to reducing warming-causing greenhouse gas pollution in the first place, and adaptation, which refers to adjusting to the effects of climate change. At previous United Nations climate conferences, countries have already established mitigation and adaptation funds. The need for a separate loss and damage fund continued to grow in the meantime, with researchers estimating that the price tag for loss and damage will be between $290 billion and $580 billion per year by 2030.

The U.S. has been the biggest roadblock in negotiations, according to developing nations. (U.S. negotiators could not be reached in time for publication.)

“We have been confronted with an elephant in the room, and that elephant is the U.S.,” said Ambassador Pedro L. Pedroso Cuesta, a representative of Cuba who is chair of the developing countries’ negotiation bloc. “[The U.S. has] come with a fixed idea: It’s either the World Bank or nothing.”

The U.S. opposed a loss and damage fund, but when international support for a fund reached a tipping point last year, U.S. negotiations reluctantly agreed to sign on. In the past, the country has been accused of employing diversionary tactics and “linguistic acrobatics” in an attempt to prevent a loss and damage fund from being set up.

Developing countries and climate justice organizations want a nimble fund that can deploy money quickly in the aftermath of a major natural disaster. In the past, setting up programs at the World Bank has taken years, and the institution has been slow to disburse funds. When nations are battered by hurricanes or face other natural disasters, the loss and damage fund needs to be able to respond to such catastrophes rapidly, developing nations say.

The World Bank also approved a new financial framework in 2019 that is “actually quite restrictive,” according to Liane Schalatek, an associate director with Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, a political foundation affiliated with the German Green Party. “One of the core issues for us is that it restricts implementing partners to just multilateral development banks, the International Monetary Fund, and United Nations agencies. We really see that as an impediment, and we know we only have one shot at a fund.”

Wealthy nations counter that the World Bank is an appropriate host because of its expertise managing programs that deploy funds to developing countries. “The developed countries are keen on the World Bank hosting the fund, using the argument that it has global presence, existing infrastructure including legal capacity and other expertise that can be drawn upon for a quick start to the new fund,” said Preety Bhandari, a senior advisor at the nonprofit World Resources Institute who has been observing the loss and damage fund negotiations this week.

International climate negotiations hinge on a crucial classification of nations into developing and developed blocs, based on their economic stature in the 1990s. But three decades on, countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea are wealthier and significant polluters. As a result, the United States and other wealthy nations want these newly prosperous countries to also contribute to the loss and damage fund.

At issue, then, is whether all developing countries should have access to the loss and damage fund — and whether relatively rich developing nations like China should contribute. Developing nations want wealthy countries, which have emitted nearly 70 percent of carbon pollution historically, to be the major funders, and they want funds to be available to all developing nations.

But rich nations have argued that funds should only be available to those developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Wealthier nations also want the fund’s donor base expanded to all countries in a position to contribute — a tricky proposition that developing nations say is an attempt by richer nations with a longer history of carbon pollution to abdicate their responsibilities.

The fund must build on “an initial capitalization from developed countries with voluntary contributions from others,” said Pedroso Cuesto, the Cuban ambassador. “There is a clear pathway to operationalizing the fund. It needs to be able to provide direct support in the form of largely grant-based finance to developing countries particularly vulnerable to the adverse consequences of climate change.”