‘I’d love the energy spent arguing over slavery reparations to be used to save the next black kid who’s going to get stabbed’: Sir Trevor Phillips claims there are ‘more important things on the agenda’ for people of colour than revisiting historical wrongs

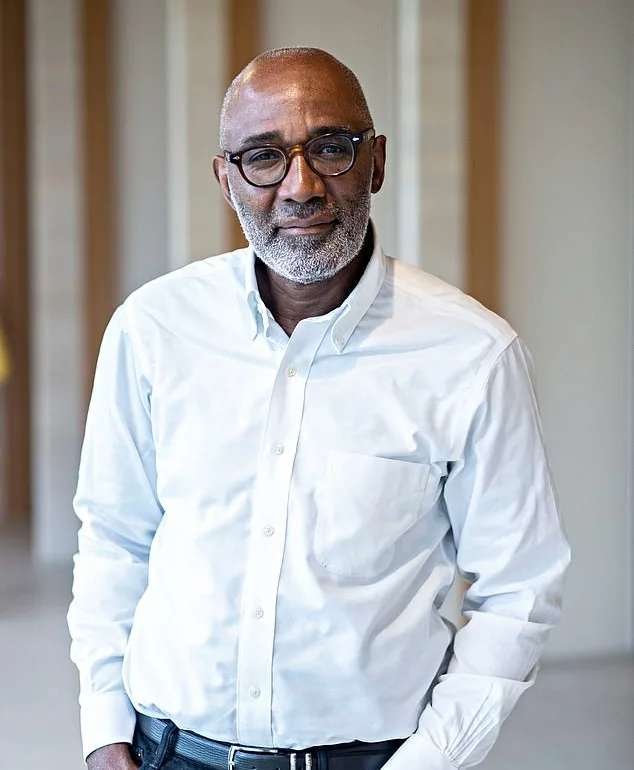

Sir Trevor Phillips is clattering around in the kitchen of his North London home making a meal for one. Or, as he calls it, ‘a lonely person’s dinner’.

The broadcaster and former Labour politician, 69, is home alone, having returned early from a family holiday in France to prepare for his new flagship political show on Sky, which launched amid much fanfare last weekend.

But as he flits between rehearsals, interviews and his consultancy day job, his mind has been elsewhere. Specifically, on the lives of his great-great-great grandparents.

For it is almost 200 years to the day that slaves in Guyana, then British Guiana, rose up in bloody rebellion against brutal conditions on sugar plantations owned by John Gladstone, the father of British prime minister William Gladstone. His ancestors, he believes, were among them.

These distant relatives were in the headlines recently after a much-publicised visit by Charles Gladstone, the Eton-educated great-great-great grandson of John, and other family members to the Caribbean to apologise for their slave-owning past.

As well as atonement, there has been talk of posthumous crimes against humanity charges, as well as demands for reparations — to the tune of several billions — for the descendants of those subjected to the indignity of enslavement. Trevor’s family has been singled out as being in line for a potential payout: something he, quite frankly, finds baffling. In fact, he finds the whole subject of revisiting historical wrongs troubling.

‘There are more important things on the agenda for people of colour than what happened 200 years ago,’ he says.

‘First of all, it — the payment of reparations — just isn’t going to happen. Who is paying reparations to whom? Is Charlie Gladstone going to send me, personally, a cheque? And if he is, why is he sending it to me rather than somebody else? I don’t need that cheque. Second: do I think that an apology to me is more important than making the life of a black teenager in Wood Green [the borough of North London where Trevor grew up] better, and fixing that young boy’s life? Not in a million years.’

This is not to say he disapproves of what the Gladstones are doing. ‘I admire them,’ he adds. ‘These are symbolic gestures, they’re good gestures.

‘But somebody falling on their knees and lashing themselves and saying how sorry they are? I don’t really care about that. That’s meaningless. I would love the energy that is being devoted to arguing over whether people who weren’t even there in 1823 should have some settlement today, to be devoted to saving the next black kid who’s going to get stabbed this weekend.’

Straight-talking, fiercely-articulate and entirely unabashed about his views on race, multiculturalism and immigration, Trevor is used to speaking his mind. As twice-serving chair of the London Assembly, head of the Commission for Racial Equality and chairman of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), as well as a long-standing broadcaster and campaigner, he isn’t afraid to provoke or offend.

What he’s not used to speaking about, however, is himself.

This week’s headlines have made him more introspective than usual, looking back on what he describes as the ‘monstrous crimes’ inflicted on his relatives.

‘Of course it makes me feel sad; one can never play them down or put them aside. I come from a very, very big family — there are hundreds of us, spread out across the globe, from the Caribbean and North America to Europe, Indonesia and Africa — and our history matters to us.’

For several years, they have been researching their family tree, uncovering unpalatable truths about an ancestor on his mother’s side, who was born into slavery in Barbados before being transported to Guyana, most likely to work on a Gladstone sugar plantation.

‘We know that her daughter was fathered by a white man,’ Trevor says. ‘We don’t know under what circumstances my great-grandmother was conceived, but I don’t think it takes much imagination. There were certainly no happy white weddings involved.’

In researching the plantations his relatives were enslaved on in the Caribbean, Trevor traced the name of one slave owner to the historical rolls of an English public school.

It was, he reveals, ‘the same English public school both my daughters attended. History has a funny way of bringing things together.’

Trevor still has close ties with Guyana today, visiting on a regular basis with his family: his second wife, TV producer Helen Veale, 53, and daughter Holiday, 35. It is important to him to maintain the connection and pass it on to the next generation. Both his parents, Marjorie and George, were Guyanese. They travelled to London by boat in 1950, and he was born three years later, the youngest child of ten.

The family were poor — at first, he says, ‘my father had to walk the streets looking for somewhere to sleep’ — and on his parents’ wages (his father was a railway worker; his mother a seamstress) they could only afford a tiny, two-bedroom house.

‘It was pre-Swinging Sixties: London was smoggy and smoky,’ he says. ‘At home, space was tight. Nobody had central heating. They used to send me for paraffin for the heater aged seven or eight, and I’d lug this big can back home. We lived in Rachman’s slum. It would be great to make it a sort of terrible sob story, but it was how everybody lived.’

Aged 15 months, his parents sent him back to Guyana, where he was brought up by his grandmother and aunt, alongside nine of his cousins. The family house was in a small fishing village on the edge of the capital, Georgetown, raised up on wooden stilts to guard against frequent floods. His memories of that time are fleeting but vivid.

‘We lived in the street with the market — the house is still there, though my family don’t live in it any more — and every Friday the women would come down from the country and lay out their fish and vegetables on the road outside our front door. It was a very poor country at that point and life was very basic. I’m not aware of ever having used an inside toilet until I was seven years old.’

At six, he came back to London for nine years, then returned to Guyana to do his school exams, before settling in the UK for good, with a place at Imperial College London studying chemistry. He became president of the student union, launched himself headlong into TV journalism after graduating and quickly became a respected racial equality campaigner.

The political string to his bow came later, in 1996, when Trevor joined the Labour Party and, after an aborted bid to become Mayor of London, served as chair of the London Assembly and went on to head the EHRC, holding the longest tenure in the body’s history to date.

That unstoppable work ethic — he turns 70 in December and is arguably embarking on his highest-profile role yet — comes from the drive and determination instilled in him by his family.

And his take on immigration, particularly the political hot potato of the small boats crisis, comes almost directly from his parents’ experience of journeying to England.

‘I am not going to pretend that my own family’s experience of getting up and out of the village, and travelling 6,000 miles on a boat to a place they had never been before won’t shape the way I look at the issue of migrants,’ he says.

‘My family would be less sentimental than many are about the process of migration. I hear people talking about how difficult and dreadful it is, and at some level that’s right. But people make that decision to do something difficult because they — like my parents — want something better for their families.

‘It’s patronising to treat them as though they’re children who’ve just got on to these boats without understanding the danger.

‘Most of the people who make these journeys know what they’re doing.’

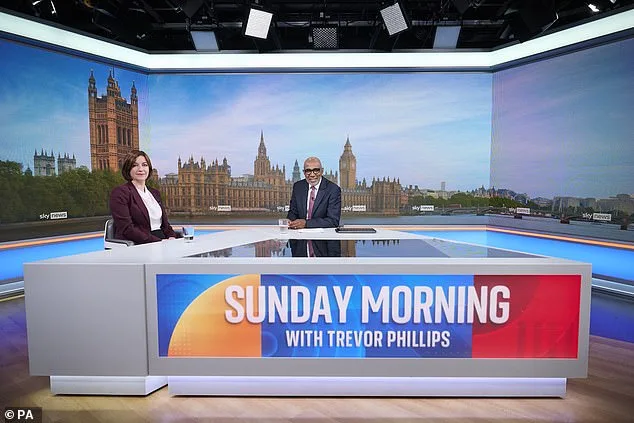

It is this sort of frank-but-informed honesty that Trevor brings to his new show, which sees him tussling for ratings alongside Sunday morning stalwart Laura Kuenssberg on the BBC — and makes him the first person of colour to host a flagship UK political show. He has promised a wider range of voices and a format that goes beyond MPs shouting over one another — as well as a focus on issues that matter to young people, specifically mental health. This is something Trevor holds very close to his heart.

His elder daughter, Sushila, 36, died in 2021 after a 22-year battle with anorexia, during which she struggled daily with her mental health and attempted to take her own life.

Trevor doesn’t like talking about the loss of his daughter, fondly known as ‘Sushi’ — something any parent will understand. But he opened up about it publicly last year, winning viewers’ sympathy during a TV interview with deputy prime minister Oliver Dowden, in which he addressed widespread anger over gatherings in Downing Street during lockdown.

Explaining how he, Helen and his first wife, Asha Bhownagary, had ‘stuck to the spirit and the letter of the rules’ by limiting contact with Sushila, despite her illness, he recalled getting a phone call in April 2021 to tell him his daughter had collapsed. She died the following morning.

‘There is no day I don’t think about her,’ Trevor says, describing Sushila, a talented freelance journalist, as ‘my collaborator’. ‘She left an imprint on all of us.’

At the time, he apologised for bringing personal matters into a political debate. But his views are different these days.

‘Those of us who have the privilege of anchoring these shows shouldn’t pretend that we are made of marble, and that we don’t bring any of our own opinions or emotions, or, frankly, our prejudices, to the interviews and conversations that we have,’ he says.

‘The thing our eldest daughter’s passing taught us is that we shouldn’t allow ourselves to be ruled by what other people think of us or do to us.’

This applies, too, to the enslavement of his ancestors all those years ago.

And while he understands the desire of many Guyanese, including the country’s president, Irfaan Ali, for a formal apology and financial settlement, he says the focus is in the wrong place.

‘The downside to the reparations debate is that, once again, we’re telling the story not actually of the people who were slaves but of the people who owned them.

‘They become the important people in the story, and I just cannot accept that.

‘I am a person with a story to tell, as are my children, as were our ancestors. And of course there are people who don’t like us because of our colour. We know what it’s like for people to be nasty. But am I going to spend my life trying to convert those people to be nice to me? No.’

Instead, he says, we should all be looking forward — not back.

‘When my parents travelled thousands of miles into the unknown and ended up in this country, they did it because they wanted something better for their children. I think that is what all of us want. And their destiny is in our hands.’

- Sunday Morning with Trevor Phillips is on Sky News every Sunday at 8.30am.