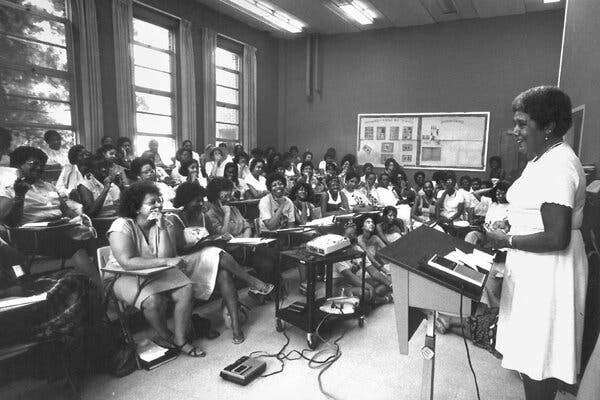

On June 24, 1983, Byllye Avery welcomed busloads of Black women to the campus of Spelman College in Atlanta. She was in a state of disbelief. The women had traveled from Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania — even as far away as California — for a three-day event billed as the First National Conference on Black Women’s Health Issues.

She had hoped that 200 women would attend; nearly 2,000 showed up.

The event inspired a remarkable change in attitudes. There were panels and workshops on high blood pressure, diabetes, lupus, childbirth and mental health. But more than addressing specific illnesses, the conference encouraged Black women to share information and consider how oppression affected their interactions with the health system. Crucially, it reframed health as inextricable from racism.

In the most popular workshop, led by Lillie P. Allen, a public health activist, women shared their stories in a space so crowded that the attendees began to remove conference room doors from their hinges and camp out in a concourse to participate. Ms. Allen took off her high-heeled shoes and stood on a platform to address the crowd.

Ms. Avery decided to organize the conference when she was researching a paper on Black women’s health. What scant information she could find told a deeply troubling story. Black women had disproportionately high rates of disease across a swath of ills — hypertension, diabetes, cervical cancer, to name a few.

One statistic, in a 1979 book of federal health data, particularly disturbed her: “More than half of the Black female adult population of the United States lives in a condition of psychological distress.” What, she wondered, was causing it? Bringing together Black women, she thought, might be the start of an answer.

After the conference, Ms. Avery and Ms. Allen decided to start a new organization: the National Black Women’s Health Project. Over five years in the late ’80s, it established more than 96 chapters. Women would gather in one of their homes in small groups, sharing their intimate concerns, their own knowledge and their stories of being ignored or dismissed by doctors. Ms. Avery and Ms. Allen also started a clinic in Atlanta that served low-income women. Those years were “absolute bliss,” Ms. Avery recalled in an oral history. In 1989, she received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant for her work.

In 2002, the organization shifted toward policy advocacy in Washington, D.C. The network of intimate groups of women who met in their communities didn’t persist, but its influence can still be felt in Black midwifery practices and health research focusing on Black women. As Loretta Ross, a scholar and an advocate for reproductive justice, pointed out in a 2006 oral history, “It seeded a whole way of thinking about the relationship between empowerment and health.”

Hidden tolls on health

Ms. Avery was in graduate school at the University of Florida in 1970, married and raising two small children, when her husband, Wesley, died suddenly from a heart attack. His doctors had told him he had hypertension, but had not explained the potential consequences. He was just 33 years old.

Ms. Avery said her husband’s death was a “radicalizing experience” that changed her life focus. She joined the growing women’s health movement and became a health educator.

The book “Our Bodies, Ourselves” had recently been published, and feminists were questioning the orthodoxy of the medical establishment. In 1974, Ms. Avery and two other women opened a feminist health center in Gainesville, Fla., that provided abortion and other services. But few Black women showed up for the well-woman services.

“Most of us, when we hear the word ‘woman,’ ‘women’s health,’ we think, white women,” Ms. Avery said in an interview. “That’s the way racism has affected us.”

The founding of the National Black Women’s Health Project was meant to address that. Taking up residence in a two-story clapboard house in Atlanta, the project set out to redefine health and wellness. Nearly 30 years before the World Health Organization issued a declaration asserting that social determinants like education, income and housing could affect health, the women at the project were talking about the mental and physical effects of oppression on Black women.

A peer-to-peer counseling process, which Ms. Allen called self-help, was the heart of the organization’s work. Jennie Joseph was a member of the Orlando, Fla., chapter in the early 1990s. A midwife trained in Britain, she credits the group with giving her “support, mentorship and love.” Like many of the women in the self-help groups, Ms. Joseph felt mistreated by medical professionals. After surgery intended to remove an ovary affected by endometriosis, “I woke up without my uterus and both ovaries,” Ms. Joseph said.

She went on to establish a birthing and midwife-training center in the Orlando area, earning her the distinction as one of Time magazine’s 12 Women of the Year in 2022 for her work combating Black maternal morbidity and mortality. Even more than health education or emotional support, the self-help groups had an explicitly political aim: to empower women like Ms. Joseph to push for change in their communities.

In Atlanta, the Center for Black Women’s Wellness — the project’s health care center for low-income women — offered low-to-no-cost health care, in addition to mental health services, job training and economic empowerment programs. Hundreds of women attended self-help groups at the center, where they could talk about issues that were difficult to broach elsewhere, such as sexual violence they had experienced at home.

The silence around family violence within Black communities was a subject then being explored by Black feminist theorists and writers like Audre Lorde and Alice Walker. One woman who was treated at the center told a researcher in the early ’90s that “I was always told not to talk, not to tell anything” about violent beatings by her husband. That changed. “Since I came to the center, I’m able to talk more about it now,” she said. “And I feel at ease, and I’m not alone.”

Alicia Bonaparte, a professor at Pitzer College who specializes in medical sociology, connects the National Black Women’s Health Project to a lineage of Black midwives, sororities and mutual aid societies that have pressed for public health in their communities. The self-help groups were places “where someone can acknowledge and say: ‘I see you. I know what your experience is like. Let’s talk about that, and let’s also figure out ways to advocate,’” Dr. Bonaparte said.

One effect of this work was “increased awareness that health is political, that health is impacted by race and gender and class and sexuality,” said Sami Schalk, assistant professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin.

In the early ’90s, Linda Villarosa, who attended the Spelman conference, was the executive editor at Essence magazine and working on a book about Black women’s health sponsored by the project.

Ms. Villarosa would visit the Atlanta house after completing each chapter and sit through a rigorous, daylong feedback session with Ms. Avery and a panel of 12 Black academics and health professionals.

“This tribe of women helped me put that book together and made it better and made it more political, made it stronger, made it more than just a Black woman’s self-help book,” she said. The stories she heard in the self-help groups “really changed the way I thought about what happens to Black women in the health care system,” Ms. Villarosa said. Her 2018 New York Times Magazine cover story about Black maternal mortality and infant mortality helped attract national attention to a deepening crisis.

The legacy of opening up

Many of the health issues that the National Black Women’s Health Project was founded to address have proven to be depressingly persistent. Black women still face higher rates of hypertension and diabetes than white women and are more likely to die of breast cancer. They account for more than half of new H.I.V. diagnoses despite making up only 13 percent of the population. And the maternal mortality rate for Black women remains a national shame: In 2021, it was 2.6 times higher than that of white women — the third straight year of significant increases in Black women’s pregnancy-related deaths.

But some things have changed. Black women live about two and a half years longer today than 40 years ago. Back in the early 1980s, Ms. Avery remembered being so frustrated by the lack of research on Black women’s health that she “threw one book across the room, and it stayed there for three or four days.” Today, there is an ongoing, nationwide longitudinal health study of 59,000 Black women; there are birthing groups, like Sista Midwife Productions and the National Association to Advance Black Birth, that help Black women navigate the medical system during pregnancy; and there is the Tufts University Center for Black Maternal Health and Reproductive Justice, which researches and supports Black women’s health.

Ms. Avery, 86, lives in Provincetown, Mass., with her wife, Ngina Lythcott. She is retired but still attends events held by the project, which changed its name to the Black Women’s Health Imperative in 2002, showing up in her trademark cropped salt-and-pepper Afro and purple lipstick. Several local and state organizations that started out with the project are still active as separate nonprofits. The Center for Black Women’s Wellness in Atlanta still provides programs for women and teen girls on maternal health and economic self-sufficiency. But it now offers care for men and children of all ages, too, and expanded last year to accommodate 2,600 clients.

Reflecting on the project’s transition away from self-help groups, Ms. Avery said, “When it came to an end, oh my God, did I mourn it.” But eventually, she said she came to believe that the project accomplished its goal of equipping Black women to change their own lives. “The best part of this whole work,” she said, “is that it has become ingrained and thoroughly integrated in the hearts and souls of Black women and their families.”

Do you have a connection to the 1983 event?

This story is part of a series, Progress, Revisited, in which we’re exploring progress toward and away from racial equity and justice for Black Americans. Forty years ago, nearly 2,000 women convened on the campus of Spelman College in Atlanta. Over the course of this three-day event, Byllye Avery and the women in attendance reimagined what medical care could look like for Black women in the U.S. With that in mind, we have three questions for you to think about: 1. Did you attend the 1983 conference on Black women’s health on the Spelman Campus? 2. Are you close to someone who was? 3. Are you part of a health-focused self-help group? If you answered one or all of these questions, we want to hear from you.

The Headway initiative is funded through grants from the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors serving as a fiscal sponsor. The Woodcock Foundation is a funder of Headway’s public square. Funders have no control over the selection, focus of stories or the editing process and do not review stories before publication. The Times retains full editorial control of the Headway initiative.