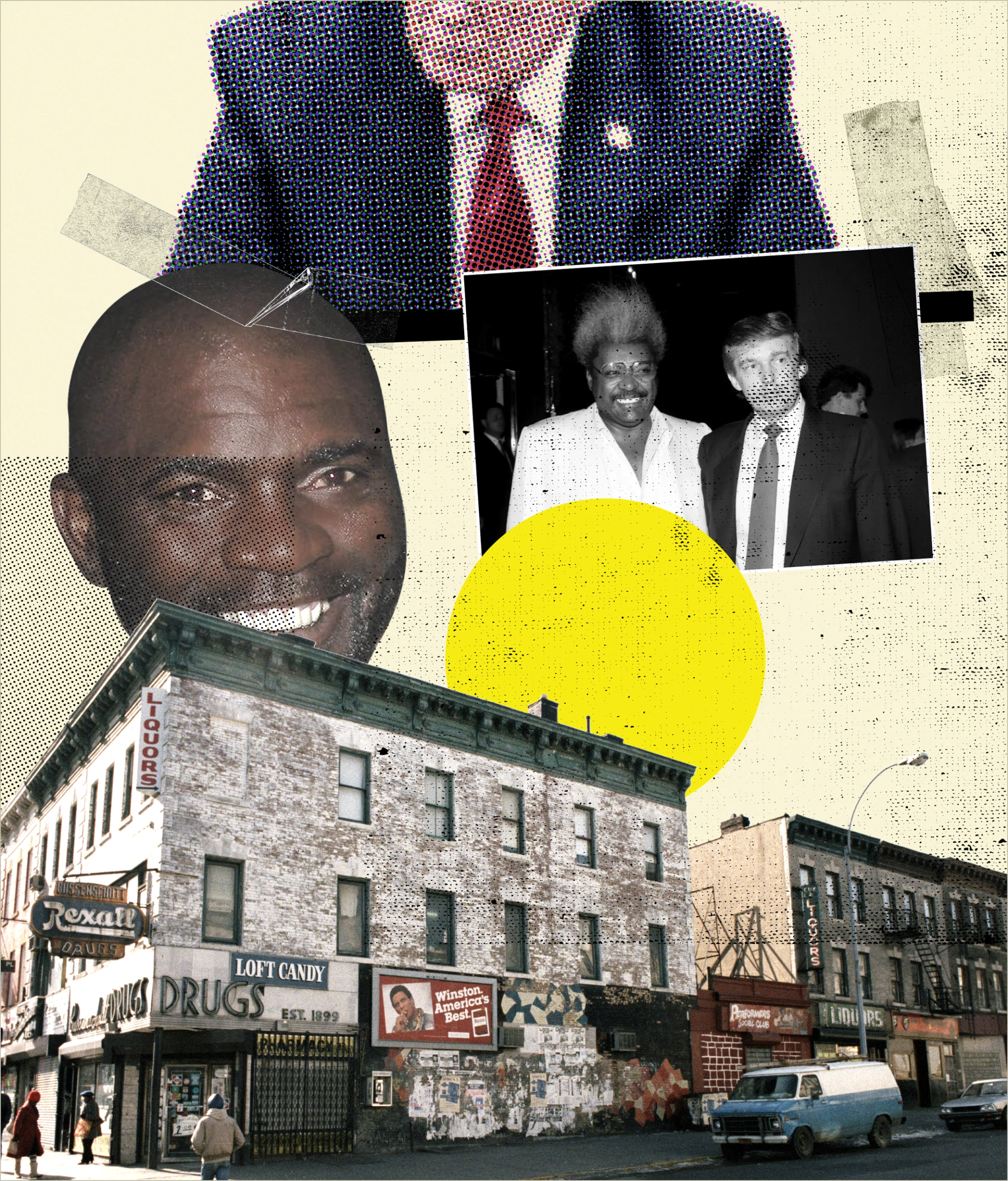

Trump’s aides seemed to think I might understand their candidate because I was shaped by the same New York era. I grew up in Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s at the nexus of these two Black Americas, where ordinary folks and celebrities meet. When I was in my early twenties, I worked at Dooney & Bourke in Trump Tower, selling leather handbags to tourists. I knew Tyson as a global icon, but also as the local bigshot who ran in the same circles as my childhood friends’ older siblings.

And so a couple of weeks after I pitched the campaign an interview, I was in Wildwood, New Jersey talking to Taylor and his old Giants teammate Ottis “OJ” Anderson at a Trump rally. Taylor’s case for Trump was one I’d heard from voters many, many times before.

“He’s going to speak his mind,” he told me. “He doesn’t care how it comes out.”

He added, crucially: “He’s a man’s man.”

Taylor, like all of the names I had been put in touch with, had a business relationship with Trump at some point as well as a social one. He recalled meeting Trump when he tried to poach him as part of a failed football venture that briefly competed with the NFL. “He put a million dollars in my account and said, listen, he wants me to play — and we’ve been friends ever since,” he said.

At the time of that rally, Trump was still on trial in a Manhattan court over hush money payments to an adult film actress ahead of his first election; he faces three more pending criminal trials in state and federal courts. It was a problem his friends could relate to.

Taylor, who was plagued by off-field issues throughout his Hall-of-Fame playing career, pleaded guilty in 2011 to patronizing a 16-year-old prostitute. (He said he believed she was 19). Trump stood by Tyson in the 1990s while he was jailed on a rape charge that he denied (he also was hosting his fights, which required the boxer to be out of jail). In 2016, the then-chairman of the Republican National Committee, Reince Priebus reportedly intervened to keep King off the 2016 convention stage because of his prior manslaughter conviction.

“The party could not associate itself with someone convicted of a felony,” the New York Times noted at the time, which might as well have been a thousand years ago.

Strawberry came out the other side of drug addiction and jail to become an evangelical preacher. When I spoke to him, he mentioned that he and other sports stars know what it’s like to face the burning gaze of the public, something he connected to support for Trump.

“People are hoping that he comes back, a lot of athletes,” Strawberry said. “A lot of times people are afraid to say — they’re afraid of public opinion, and I’ve had public opinion my whole life…they were saying I couldn’t survive, I couldn’t make it. And guess what? I’m still here.”

Trump’s gains with nonwhite voters in the polls have mostly come from younger Americans. When I mentioned to Trump during our interview that the people that I’d been directed to talk to all seemed to be associated with a certain bygone period, he immediately thought to add another name to the list.

“Did you give her Herschel?” he asked his staff.

He was referring to Herschel Walker, the former football star who lost his Senate race last cycle while facing political attacks over allegations of past domestic abuse and previously unacknowledged children. A born-again Christian, Walker told voters at the time that he had moved past a dark period of mental illness and was reformed.

A few days later, I received a call from Walker, who adores Trump. He recalled how they became close in the 1980s, when he was also involved in Trump’s football endeavors. Walker volunteered to take a young Don Jr. to Disney World with his own family while his team was at training camp in Orlando. The ease with which a white New York businessman befriended “a Black kid who came from this little town with absolutely nothing,” made a strong impression.

“I know the man has got a great heart,” he said.

Walker rejected the premise that Trump had a problem with Black voters — he said he was sick of being asked to “defend” him as a Black man, as if supporting Trump required an extraordinary explanation. His advice to the campaign was to start showing up more often in Black neighborhoods and to treat voters the same as they would white voters.

“What I told Don is I think you need to go see more Black people in the cities and talk to them,” he said. “I said, you know, they love you.”