I agree with many of Daniel Philpott’s assertions about biblical justice, forgiveness, and reconciliation concerning American blacks. But providing reparations for all blacks in America is not only unrequired by the demands of justice; it would also be ineffective and impractical.

An Apology Is Needed

Let me start with where I agree. America must apologize for the ills of forced slavery and coercive racial segregation.

Consider the United States’ response after it placed the Japanese in internment camps during World War II. In 1988, the United States government apologized to the Japanese and offered compensation to those who were interned. This apology—and compensation—were a step in the right direction to achieve a form of justice.

However, with their taxes, living American blacks who had lived under segregation paid into the reparations given to the Japanese. Considering this, we must ask why America apologized to and compensated the interned Japanese, yet American blacks still have not received an apology for slavery, for racial segregation—a destructive form of racial discrimination—or compensation for either one. The longer it takes for the United States to apologize, the more the nation seems to purposely distances itself from genuine justice.

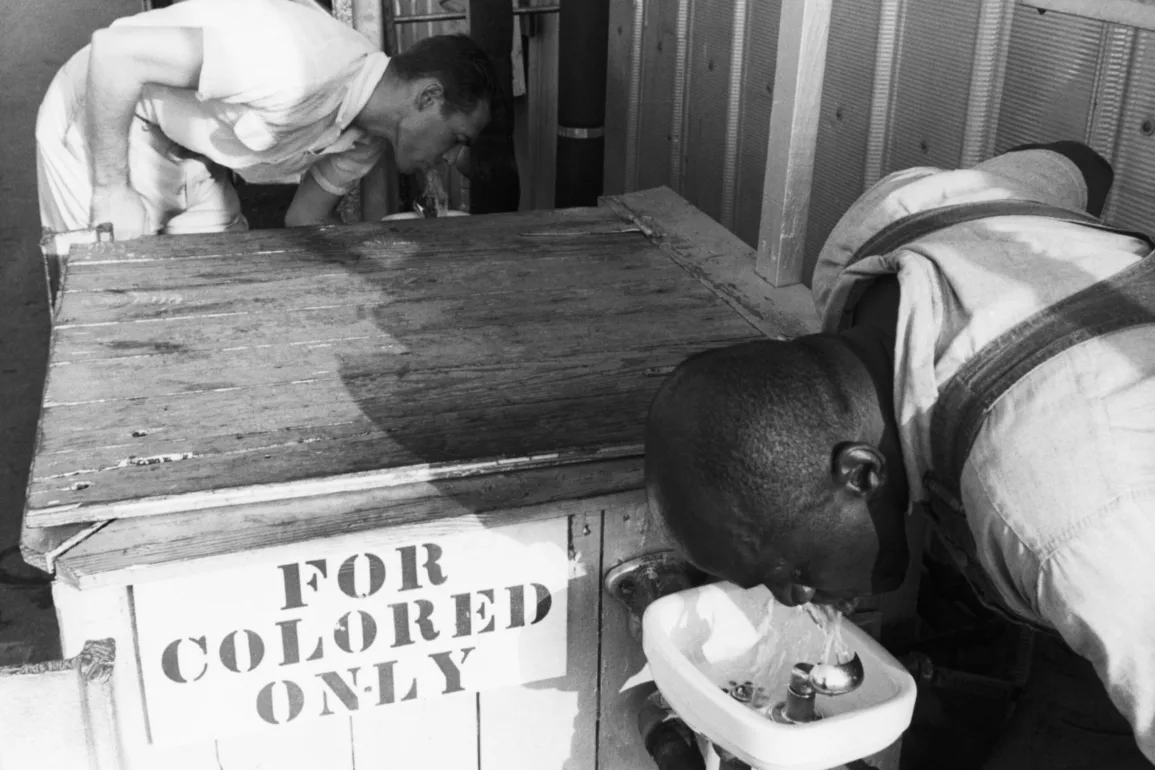

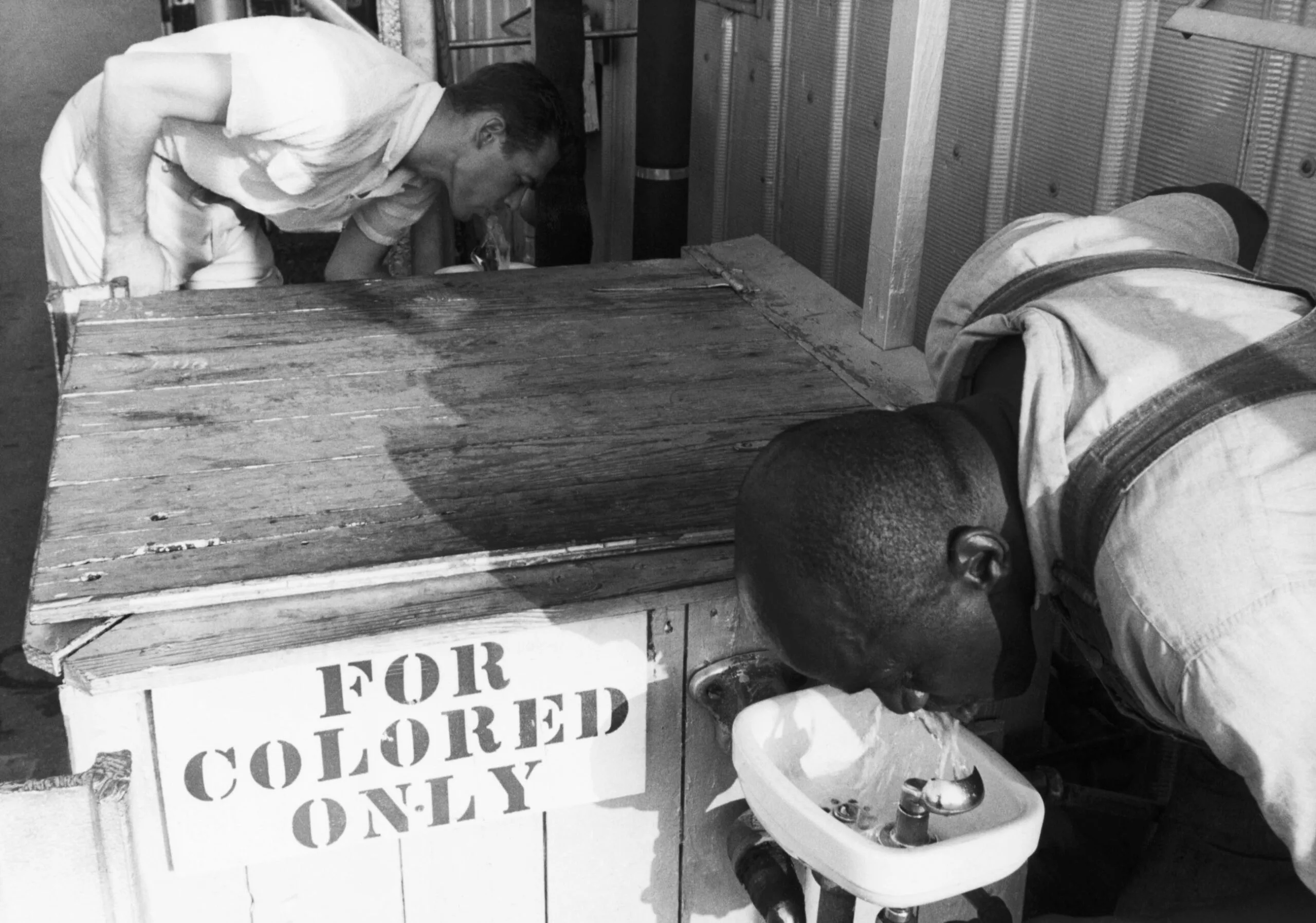

American blacks need an apology, primarily because the Supreme Court’s unconstitutional ruling on the 1875 Civil Rights Act unleashed a new era of oppression—racial segregation—for blacks living in the American South. There has been no apology from the United States government as a whole. The House of Representatives did issue an apology when Barack Obama was elected president, but the Senate did not sign on, and the federal government has communicated no remorse.

The US government’s lack of an apology suggests that it dismisses its participation in slavery and racial segregation of American blacks. This dismissal has prevented American blacks from being thoroughly American. Segregation rejected blacks’ constitutional rights and privileges, and consequently, people willfully treated blacks as despised, second-class citizens. Until an apology is issued for these grave wrongs, injustice continues to fester.

Christian Apologies

The absence of an apology from the US government for slavery and racial segregation is even more egregious, considering the fact that many Christian denominations have issued apologies. Many predominantly white denominations theologically justified slavery and, ultimately, racial segregation. In colonial America, white denominations argued that it was noble to baptize enslaved people and convert them to Christianity to save their souls without granting them freedom. Specific laws stated that conversion and baptism did not exempt them from bondage.

In 1994, Pentecostals apologized for the racial divisions in the church. The United Methodist Church “confronted more than 200 years of institutional racism and discrimination that split John Wesley’s Methodist followers into two distinct camps–black and white” in 2000. The Episcopal Church apologized for failing to oppose slavery and segregation in 2006. The Southern Baptists acknowledged their moral failings in endorsing slavery, enduring racism, and segregation– for which they apologized in 1995, 2009, and 2018. In 2009, The Unitarian Universalist Association apologized for white supremacy, the enslavement of blacks, and prioritizing white identity as racially superior to others in its denomination. In 2015, the Nassau Presbyterian Church apologized for its long history of racism in Princeton against the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church for removing Reverend William Robeson. In 2016, The Presbyterian Church in America apologized for its racist actions during the civil rights era. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America apologized “to people of African descent for its historical complicity in slavery and its enduring legacy of racism in the United States . . .” in 2019. In 2022, the Presbytery of Lake Michigan offered the document, On Offering an Apology to African Americans for the Sin of Slavery and Its Legacy, to apologize to blacks for white supremacy, the degradation blacks faced, the idea that those of European descent are superior in intelligence, and repenting of violent actions to “suppress Black agency,” among other things. The Episcopal Diocese of New York apologized for its “affiliation with the transatlantic slave trade and the oppression and exploitation of enslaved people” in 2023.

Considering that these denominations properly apologized for their overt mistreatment of blacks, it is grievous and lamentable that the US government still fails to apologize for the series of oppressions blacks faced. Philpott is right to point this out.

Right Relationship

Philpott also said, “Justice in the Bible means comprehensive right relationship, and it involves obligations that are owed to others as well as actions that exceed what is due and are guided by generosity, mercy, the giving of a gift, the pursuit of reconciliation, and forgiveness.” I agree with him here too.

What might this look like in practice? Some people who are still alive contributed to the damage done to American blacks. Those who sinned against blacks, many of whom were Christians, must provide restitution. Compensation was necessary back then and is essential now for those who had to live under racialized and discriminatory laws.

Indeed, these men and women who contributed to the destructive nature of racial segregation may have asked God for forgiveness. However, they still must make the situation right in the eyes of God and their country. This point underscores Philpott’s perspective that “past injustices merit public acts of reparation, which are measures of justice.” This declaration is correct. The people who contributed to the second-class status of blacks must pay restitution to those not allowed to be part of mainstream America. The best way to achieve restitution for segregation is to do what we did for the Japanese who were placed in internment camps: pay reparations.

Black Americans who lived under segregation were deprived of both their human dignity and their rights guaranteed by America’s political documents. As Philpott rightly suggests, “All looked to the natural rights of the Declaration of Independence as the truth that judged slavery and subsequent racism as unjust and contrary to the nation’s purposes.” The Declaration of Independence specifies that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Despite the ideals contained in the Declaration of Independence, the states violated them precisely because they denied the equality of American blacks. The justification for this contradiction, the denial of equality, was based on the refusal to acknowledge the humanity of blacks.

Who Deserve Compensation?

That said, here is where I disagree with Philpott. The problem is that not all forty million blacks alive today in America have experienced the patronizing discrimination blacks faced during racial segregation. The 1964 Civil Rights Act ended racial segregation, the most prominent example of “institutional racism” or “systemic racism” the country had seen since slavery. That is not to say blacks have not faced difficulties, but their difficulties are not the product of “systemic racism” or “institutional racism.” Instead, many of these difficulties stem from the lack of black mothers and fathers getting and staying married for their sake, but mainly for the sake of their children.

Only one segment of American blacks rightly deserves compensation: those still alive who lived under racial segregation. As mentioned, American blacks’ money was used to compensate Japanese survivors of internment camps. But during segregation, people despised American blacks, and numerous southern states damaged their dignity and equality. A genuinely worded apology and compensation from Congress and the president of the United States would be fair and allow the initial steps toward offering survivors of racial segregation a form of biblical justice.

However, we cannot compensate enslaved people in present-day America because they are no longer with us. That does not prohibit an apology, which (to reiterate) is needed, especially considering enslavers in the District of Columbia received compensation after the federal government ended slavery. Many American blacks, myself included, are descendants of enslaved Americans. As Philpott correctly says, apologizing is a step toward “forgiveness and reconciliation.” The permanent refusal to apologize has led to bitterness, racial division, and the idea that somehow, America does not need to apologize and make restitutions for its evils—which means America is further away from forgiveness, reconciliation, cultural unity, and loving its neighbor.

Ineffective and Impractical

Efforts to compensate or advantage all blacks today are unnecessary as a matter of justice, and these efforts have unintended consequences. Before the Supreme Court ended race-based affirmative action, some American blacks had received admission at high-level academic institutions, sometimes at the expense of whites and Asians with higher grade point averages and SAT and ACT scores. Many of these blacks dropped out because they could not keep pace with fellow students or their teachers. They were mismatched and granted admission to colleges and universities for which they were unprepared. Had they attended schools commensurate with their preparation, the dropout rate would have been lower, and the graduation rate would have been higher.

Those who pursue reparations to shrink the wealth gap and improve the livelihood of blacks would be better off encouraging higher marriage rates. In 2020, the Hispanic marriage rate was 43 percent, the white marriage rate was 52 percent, the Asian marriage rate was 58 percent, and the marriage rate for black immigrants was 61 percent. That same year, only 30 percent of blacks were married—compared to the national marriage rate of 48 percent.

Fifty-two percent of black men and 48 percent of black women have never been married. The black marriage rate in 2021 was 29.7 percent, and the number of black children that lived in single-parent households in 2021 was 64 percent, compared to 42 percent for Latinos, 24 percent for whites, and 16 percent for Asians. If we are serious about closing the wealth gap between blacks and whites—and parents creating biblically moral and academic excellence among American black children—we must encourage marriage among blacks, regardless of class. This issue is one that far too many people ignore or choose to blame on “structural racism” when, in reality, marriage rates in black communities are not as high as they are in Hispanic, white, Asian, or black immigrant communities, which, in turn, inescapably produces wealth gaps.

Again, the United States must apologize for treating blacks with contempt and compensate with reparations those American blacks who lived through racial segregation. But reparations for all black Americans will not erase the wealth gap between blacks and whites, or improve the significant educational achievement gap rampant throughout the black communities in this country. The wealth gap exists because blacks are not marrying at the same rates they did while they were under racial segregation. The lack of two-parent households reduces academic excellence among blacks, who might otherwise be on par with whites and Asians.

In present-day America, an apology and reparations for survivors of racial segregation are a matter of moral and biblical clarity, justice, forgiveness, reconciliation, and national unity. But the nation must limit reparations; a $9.6 trillion price tag is far too steep. It can only be for those that experienced racial prejudice during segregation. American blacks under Jim Crow had to live with sections of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments eviscerated. They were condescended to, and generally not regarded as not comprehensively American. They deserve reparations, but reparations for all 40 million black Americans can’t be justified.