The freeway that bifurcated North Omaha was marketed as an infrastructure development that would benefit all of Omaha. However, it solidified segregation, dramatically decreased Black homeownership and led to the amplification of environmental injustice.

For the last two years, I have been working as a research assistant for the Omaha Spatial Justice Project. As part of that project, I helped develop the project’s 1920 Black homeownership map, which shows a high concentration of homeownership along the North Freeway. Black homeownership reached a peak in 1950, when for the first time, there were more Black homeowners than renters.

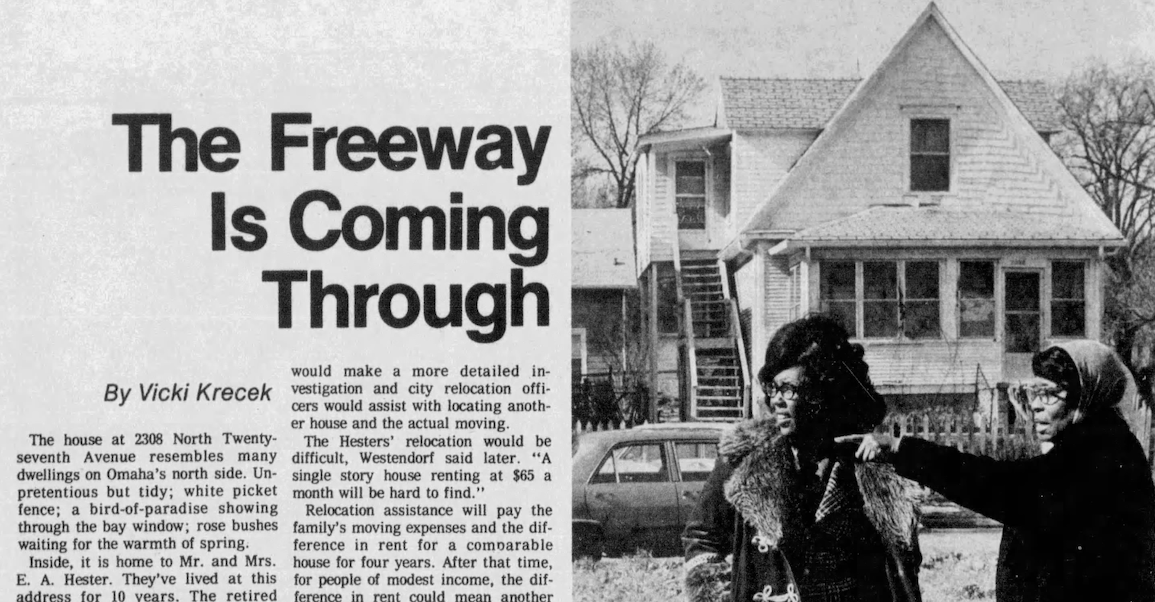

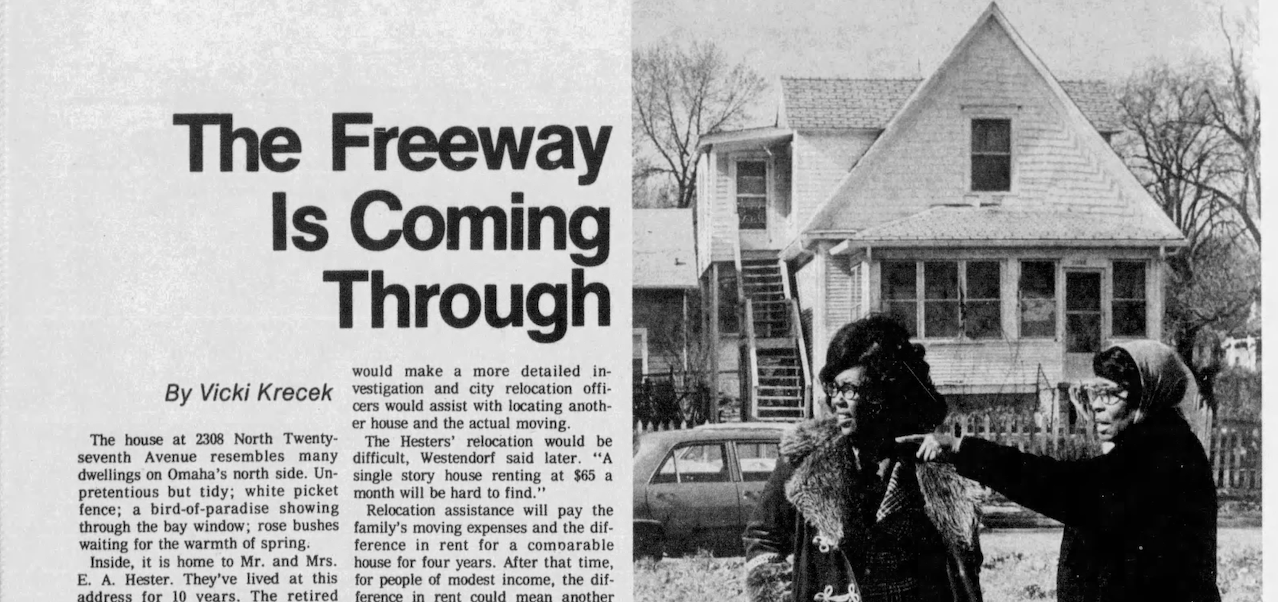

Many homes were demolishedfor the freeway construction, stripping Black homeowners of their already limited access to generational wealth. The areas with rentals were left mostly untouched, whereas the neighborhoods that consisted primarily of homeowners were the ones replaced by the North Freeway. This demolished housing was not replaced, and due to persistent racism, Black homeowners received little to no compensation and found it difficult to purchase homes in other neighborhoods.

North Omaha was cut off from the rest of the city, resulting in limited access to public transportation and basic needs and services. Because of this, as Omaha developed further, food deserts, or areas with a decreased or complete lack of access to affordable healthy foods, manifested as a concern. This was exacerbated by the national trend of grocery stores shifting to suburban areas which began in the 1960s. While grocery stores still existed in North Omaha, new stores with healthier inventory were not accessible to neighborhood residents, resulting in disproportionate access to good quality food increasing health risks.

The North Freeway displaced thousands of Omaha’s Black residents, restricted access to homeownership, and led to an increased prevalence of environmental injustice issues that can be linked to present-day inequities. Because of this, there is a need for restorative justice.

In 2016, Catherine Millas Kaiman, a civil rights and environmental activist attorney, presented a national model for community-based reparations to achieve justice, by addressing issues of environmental injustice through funding awareness campaigns and education. Another path to justice is to provide reparation payments to relatives of individuals whose homes were destroyed. Affected individuals could make a claim examining how far below market rate compensation payments were to then make up the difference with interest.

Omaha’s construction of the North Freeway caused displacement, along with accompanying housing discrimination, amplifying environmental injustice. There is a critical need in North Omaha to address the problem of food deserts, including a lack of food availability as well as better access to affordable healthy food.

Omaha must come to terms with the damage done through a community-based reparations solution. Washington, D.C., provides a national example of how one city chose to confront the issue of food deserts. After identifying the locations of food deserts, the city offered financial incentives for businesses that opened grocery stores in those areas. The City of Omaha needs to implement a comprehensive policy solution to address this pressing need for the long-term health and stability of the community.

Any policy solution must address the historic wide-scale dismantling of Black homeownership through a housing reparations program. A national example of this is Evanston, Illinois, where the city clerk in 2019 made a case for housing reparations, and the first program in the country was implemented by the city council in 2021 to compensate the Black community for historical policies of segregation. It’s important to know whether the families that were affected by the destruction of their homes via the North Freeway believe that an injustice took place and reparations are needed.

Recently, there have been increasing plans and funding for development in North Omaha. Before the city implements redevelopment, we need to right the wrongs of history. As Omaha moves forward with new plans for development, there is a need to address the task of increasing Black residents’ access to homeownership. For Omaha to move on, we must address this difficult past.

The Omaha Spatial Justice Project is providing documentation of historic discrimination in Omaha by mapping racially restrictive covenants. Residents affected by housing segregation, the lack of access to homeownership and environmental injustice need a space to propose their solutions for reparations. The City Council and Mayor’s Office need to seriously consider and creatively implement these community policy solutions.