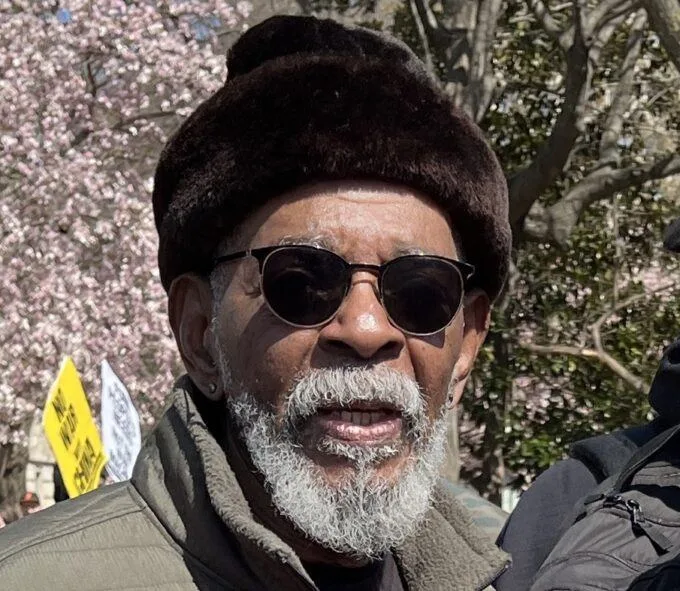

American political activist Omali Yeshitela on 18 March, 2023. Photograph Source: The Burning Spear – CC BY 2.0

In their 1999 song “Police State,” the rap duo Dead Prez took a disturbing look at the prison system, poverty, economic exploitation, and domestic surveillance of the Black community. In keeping with Dead Prez’s revolutionary Black socialism, the song opens with a spirited speech describing the state as “a repressive organization” and observing the connection between one’s economic class and his subjection to America’s abusive criminal justice system. The voice delivering the speech belongs to Omali Yeshitela, who helped found the African People’s Socialist Party in 1972, and who remains its Chairman today.

Yeshitela and several others associated with the African People’s Socialist Party were indicted by the Biden administration last year, hit with charges of spying for and working with the Russians. The indictments followed years of harassment, as well as violent FBI attacks on the Party’s offices in Florida and Missouri. The defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the case was argued this week, though the case has received remarkably little attention from the legacy media. Historically, this charge of spying is among the U.S. government’s go-to accusations when it doesn’t care for a radical group’s political speech and activities. The U.S. government knows it cannot compete in the marketplace of ideas we hear so much about.

Cases like this one must be understood within the appropriate historical context. It is vital to underscore the fact that these indictments—and the use of law enforcement and legal systems to punish dissidents—are not an aberration. They are consistent with a broader historical program of violent attacks on activists in our country. The federal government has a long and sordid history of targeting civil rights organizers, anti-war activists, socialists, labor unions, anarchists, and other political radicals.

Through its COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) initiatives, the FBI behaved as the United States’ secret police, illegally and unconstitutionally interfering with legitimate political activities and denying citizens due process. COINTELPRO was the then-Director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover’s brainchild, launched at the height of the Red Scare and dedicated to undermining activist movements under a broad program of secret activities. The program began in 1956, about a decade before the passage of the Freedom of Information Act. Among the FBI’s key tactics during this period were attempts to infiltrate activist groups and sow discord and disinformation, even fabricating assassination threats. Among the most actively targeted groups were the civil rights movement, the American Indian Movement, anti-Vietnam War activists, and the Black Panther Party. In its many harassment and disinformation campaigns, the FBI leveraged personal information, frequently obtained in violation of the Constitution, as blackmail, engaging in threats and psychological warfare. (Perhaps the most well-known example of this was the FBI’s attempt to push Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to end his own life.)

As the group grew in prominence, the Black Panthers were infamously put in the crosshairs of the FBI’s COINTELPRO, which sought “to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of the Black nationalists.” They were spied upon, infiltrated, and harassed for years at the hands of the FBI. Indeed, in 1969, Hoover said that “the Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” The Black Panthers represented a challenge to the status quo because they wouldn’t play by rules imposed by the power elite: participate in narrowly prescribed, two-party-but-single-ideology electoral politics that neither countenance radical change nor challenge the fundamental psychological predicates of racism, authoritarianism, or capitalism.

Huey Newton and the Black Panthers presented a clear and direct challenge to the violence at the heart of white supremacy and the second-class citizenship for Black Americans that endures today. Newton was a realist and understood the unmentioned mechanisms of violence upon which hierarchical power structures like racism depend. “The power structure,” Newton argued in 1967, “depends upon the use of force without retaliation. This is why they want the people unarmed . . . . An unarmed people are slaves or are subject to slavery at any given moment.” Under this view, mainstream liberal promotion of “gun control” was a case of white privilege and white supremacy, reflecting the country’s historical two-tier social system: whites could expect to be protected by the police, whereas, again in Newton’s words, “Black people are held captive in the midst of their oppressors.” The United States government saw this level of awareness and self-respect as a threat to its power. The Panthers believed that they could help their communities from within, without the help or influence of white supremacist elites in government and corporations. They empowered their friends and neighbors to support each other directly as a community. They fed people and taught them solidarity, helping their neighbors to organize and see themselves as agents of change capable of generating a wave of equality and justice.

This was unacceptable to a United States government obsessed with eradicating grassroots leftist movements. Then, as now, radical or socialist leanings provide the pretext for questioning one’s loyalty to her country and for working around and outside of formal legal and constitutional protections. We must understand COINTELPRO’s attacks on Black activists within this historical context, as an episode in a larger story of the Red Scare, McCarthyism, and bogus charges of imagined or fabricated secret plots. Some of the infiltrators working for the FBI later went public and admitted their involvement in tactical missions to destroy the Black Panthers; Louis Tackwood, for example, recounted the story of the FBI’s (together with local law enforcement) concerted efforts to destroy the Los Angeles office of the Black Panther Party and, in particular, Geronimo Pratt, using surveillance, harassment, groundless arrests, and false accusations. As Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall pointed out in Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement, the federal government designated Pratt a “Priority I” national security threat on the recommendation of the FBI, despite “virtually no evidence” being offered other than a bogus “biography” authored by the Bureau itself. Pratt’s story is just one of dozens of examples of COINTELPRO operations aimed at minorities with the wrong politics.

It has become popular practice today to describe these oppressive tactics as “extra-legal,” but within the appropriate historical context, such tactics are the law’s fundamental reason for being; the law has consistently been a weapon against the powerless to shield agents of the state from accountability. The FBI’s treatment of activist groups was not “extra-legal” in any rational sense. It was conducted under the aegis of the state and the law. Had it not been for the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, an activist group that broke into a Pennsylvania FBI office in 1971, the public may never have known about COINTELPRO’s activities. We usually find out years or decades later that the government has been violating our constitutional rights, and there is almost never a real remedy. To say that the COINTELPRO era’s atmosphere of fear, paranoia, and conformity bears a striking similarity to the present moment would be an understatement. Our New Cold War is in direct continuity with the old in ideological character and affiliations, methods, and aims. Zooming out, it becomes evident that the country never left this Cold War mentality. When the Soviet Union ceased to be and the War on Terror ushered in a new era of mass surveillance, torture, murder and detention without trial, and harassment of journalists and activists, COINTELPRO had provided the model. American citizens—that is, your neighbors—are to be treated as dangerous enemies to be spied on and violated with impunity. Be on the lookout for “extremism” and “misinformation” and “if you see something, say something.” McCarthyism, like the imperialist ideology that rules the world today, depends on creating a climate of fear and a nation of unthinking, obedient tattletales. Even very recently, leaked documents have revealed FBI programs aimed at the made-up category “Black Identity Extremist,” which as always roughly aligns with activists and radicals who present compelling, real-world alternatives and challenges to the status quo. Due to the heroic efforts of Color of Change and the Center for Constitutional Rights, we have learned that the FBI tracked and surveilled activists associated with the Black Lives Matter protests in Missouri in 2014.

We have created frightening political and legal conditions in which the Constitution instantly vanishes as soon as someone is branded, however arbitrarily, a terrorist, or a traitor, or an agent of a foreign government. This has happened during every war, and there always seems to be a new one. The standards for such accusations are of course not neutral or objective, but heavily encumbered with normative positions on politics, economics, and social organization generally. But even more than that, the standards are shaped and determined by the fact that the United States cannot allow people to tell the truth about its role in the world. It focuses extraordinary amounts of time and resources to targeting dissents and suppressing alternative and independent journalism. The threat level is conveniently calibrated as needed by the leaders of the national security apparatus. Russia is an example of this phenomenon: sometimes the enemy is weakened, to be overcome imminently; sometimes the enemy is everywhere, overwhelming in power and diabolical beyond imagining. This fear lever is deployed to adjust the state-corporate complex’s control over the public.

That the words of activists fighting for peace, freedom, and equality should elicit such responses from the world’s most powerful government is telling. Even the mightiest empire has to fear these ideas, and occasionally this fear results in reluctant respect. But only if we continue to fight. That means fighting for the rights of others—in Yeshitela’s case, fellow American citizens—even if we don’t agree with them on particular issues. It is unfortunately necessary to point out that all people have a right to associate freely with others as they wish, and to think, say, and write according to their own beliefs—even if these associations and beliefs run contrary to the interests of the U.S. government. It is not a crime to be a radical. It is not a crime to oppose war or to call the United States empire what it is. It is not a crime to be both Black and a leftist, our country’s history notwithstanding. It is not a crime even to openly sympathize with the government’s enemy in a time of war. The people who want to make these things crimes are now running the federal government and using their positions of power to punish dissidents and violate the Constitution’s protection of political speech, just as they have in some of the darkest and most shameful episodes of the country’s past. If the Constitution is to be more than a mere symbol, citizens must call attention to the ongoing political persecution of dissenting voices, and to the authoritarian might-makes-right ideology of our government.