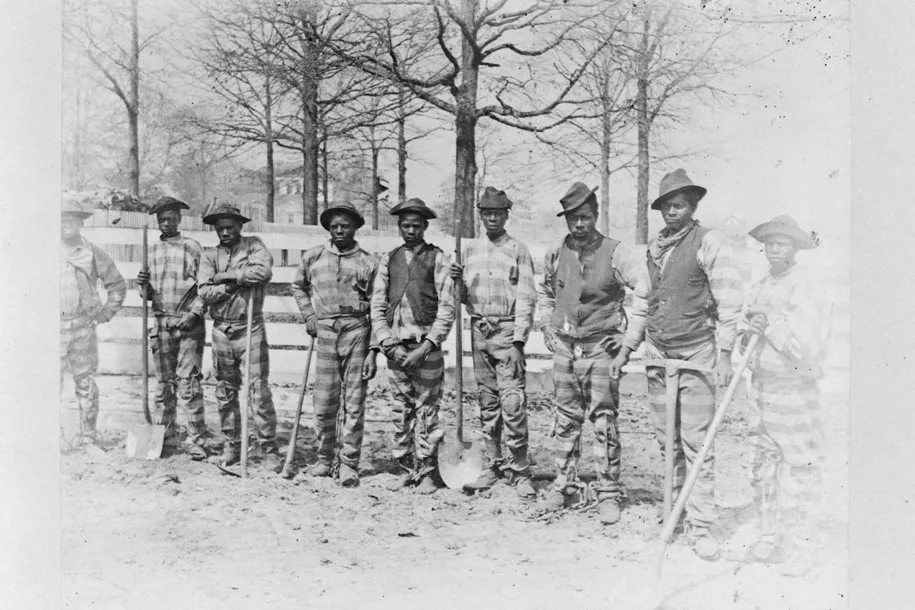

Kimberle Crenshaw: Unlike before when someone owned you, driving you too hard was counter-productive because you would lose your investment. Convict leasing was different. You could get them cheaper and if you actually drove them to death, there was more where that came from.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad (Harvard): In Alabama in 1850, 99% of people who were incarcerated were white. In Alabama by the 1880, 85% of the people incarcerated where Black. So we could have a debate, about how many of those black people were actually innocent, or we could have a conversation about the use of the criminal justice system to target both the innocent and the guity alike.

That continues all the way to the present. Where even today, about just under 40% of the nations prisoners are black, and yet the African American population is about 13%. They are snatching up bodies everywhere to fuel the system.

In 2010, the Nation’s two largest private prison companies imprisoned more than 120,000 people and took in nearly $3 Billion in revenue.

Jim Crow, Lynching and the Ku Klux Klan were a large part of the push-back against the freeing of Slave after the Civil War.

But the larger and more deadly feature of this pushback was Convict Leasing. The Black Codes implemented by bigoted police forces were used to turn the former Slaves into “Convicts” who were forced to work to pay off their fines in brutal and relentless conditions.

In February 2018, Fort Bend Independent School District in Sugar land, Texas discovered human remains in what turned out to be an unmarked grave site while constructing a school facility. By the summer the remains of 94 men and one woman, now known as the Sugar Land 95, were excavated and put inside storage pods. All of them were African American convict lease prisoners who worked and died in the sugar plantations of Sugar Land.

Archeologists found haunting evidence of dehumanization: gones misshapen from back-breaking labor, gunshot wounds, signs of malnutrition, heat strokes, even chains.

The remains were reburied where they were found, but there is no historical marker at the site or any indication of what happened there.

In the wake of George Floyd’s death outrage and protests erupted around the nation in reaction to our current form a policing. Many argued that Defunding the police was called for, and many others argued that this was a misguided approach.

“Who would protect us?”, they argued.

Before we answer that, we need to ask the question – do the police have a duty to protect us at all?

The motto, “To Protect and Serve,” first coined by the Los Angeles Police Department in the 1950s, has been widely copied by police departments everywhere. But what, exactly, is a police officer’s legal obligation to protect people? Must they risk their lives in dangerous situations like the one in Uvalde?

The answer is no.

In the 1981 case Warren v. District of Columbia, the D.C. Court of Appeals held that police have a general “public duty,” but that “no specific legal duty exists” unless there is a special relationship between an officer and an individual, such as a person in custody.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also ruled that police have no specific obligation to protect. In its 1989 decision in DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, the justices ruled that a social services department had no duty to protect a young boy from his abusive father. In 2005’sCastle Rock v. Gonzales, a woman sued the police for failing to protect her from her husband after he violated a restraining order and abducted and killed their three children. Justices said the police had no such duty.

So the answer is “no” – they don’t have any legal duty to protect the public. None at all. They can do it if they choose to, but if they do not they are protected by “qualified immunity.”

Qualified immunity provides protection from civil lawsuits for law enforcement officers and other public officials. It attempts to balance the need to allow public officials to do their jobs with the need to hold bad actors accountable.

Proponents of qualified immunity argue that without a liability shield, public officials and law enforcement officers would be constantly sued and second-guessed in courts. Critics say the doctrine has led to law enforcement officers being able to violate the rights of citizens, particularly disenfranchised citizens, without repercussion

Qualified immunity is not the result of a law passed by Congress, nor is it written in the Constitution. It is instead a legal doctrine refined by the U.S. Supreme Court. First outlined in 1967, it has since been greatly expanded. Qualified immunity is largely a creation of the courts, one that is not based on the U.S. Constitution. As such, Congress could pass a law amending, affirming, or revoking qualified immunity at any time. It has so far declined to do so. However, both lawmakers and current Supreme Court justices have considered amending or revoking qualified immunity as it currently stands.

So police have no duty to protect, and in many cases, they can be protected from personal liability for the malfeasance of their actions.

This gives them broad latitude in how and whether they apply the law.

Typically we get the argument that “most police are fine and upstanding” and there are only a “few bad apples.” But then why is it that when the DOJ does an investigation of entire departments, they find things like this?

The Justice Department announced today that it has found reasonable cause to believe that the Chicago Police Department (CPD) engages in a pattern or practice of using force, including deadly force, in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. The department found that CPD officers’ practices unnecessarily endanger themselves and result in unnecessary and avoidable uses of force. The pattern or practice results from systemic deficiencies in training and accountability, including the failure to train officers in de-escalation and the failure to conduct meaningful investigations of uses of force.

[…]

The department found that CPD’s pattern or practice of unconstitutional force is largely attributable to deficiencies in its accountability systems and in how it investigates uses of force, responds to allegations of misconduct, trains and supervises officers, and collects and reports data on officer use of force. The department also found that the lack of effective community-oriented policing strategies and insufficient support for officer wellness and safety contributed to the pattern or practice of unconstitutional force.

In addition, the department also identified serious concerns about the prevalence of racially discriminatory conduct by some CPD officers and the degree to which that conduct is tolerated and in some respects caused by deficiencies in CPD’s systems of training, supervision and accountability. The department’s findings further note that the impact of CPD’s pattern or practice of unreasonable force falls heaviest on predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods, such that restoring police-community trust will require remedies addressing both discriminatory conduct and the disproportionality of illegal and unconstitutional patterns of force on minority communities.

Almost a decade ago, former Baltimore Officer Michael Wood jr. went public on Twitter with some of the abuse he saw on the force, and described how the perverse incentives drive officers to prioritize compiling arrests and citations over actually protecting the public or the community. And how those assigned to patrol in affluent neighborhoods will go off book to get those arrest in poorer neighborhoods where the defendants are less likely to have connections and legal protection.

The consequences of generations of red-lining, segregation and Jim Crow which has deliberately corraled Black people into destitute and disinvested communities pushes and keeps them further trapped in poverty that makes them the primary prey for police to target.

Then the courts go to work on them with overworked and underfunded public defenders who far too often provide ineffective counsel and send black people to jail for hard time that is certainly not reflected in other communities. And this situation has been made worse by the Supreme Court with Gideon V Wainwright which established a Sixth Amendment right to counsel in 1965.

Race and the Disappointing Right to Counsel

[Abstract.] Critics of the criminal justice system observe that the promise of Gideon v. Wainwright remains unfulfilled. They decry both the inadequate quality of representation available to indigent defendants and the racially disproportionate outcome of the criminal process. Some hope that better representation can help remedy the gross overrepresentation of minorities in the criminal justice system. This Essay is doubtful that better lawyers will significantly address that problem.

When the Supreme Court decided Gideon, it had two main purposes. First, it intended to protect the innocent from conviction. This goal, while imperfectly achieved at best, was explicit.

Since Gideon, the Court has continued to recognize the importance of innocence claims at trial, issuing important, pro-defense decisions in the areas of confrontation, jury factfinding, the right to present a defense, and elsewhere.

The Court’s second goal was to protect African Americans subject to the Jim Crow system of criminal justice. But, as it had in Powell v. Alabama, the Court pursued this end covertly and indirectly, attempting to deal with racial discrimination without explicitly addressing it. This timidity was portentous. Gideon did not mark the beginning of a judicial project to eliminate race from the criminal justice system root and branch. Since Gideon, the Court has made it practically impossible to invoke racial bias as a defense; so long as those charged are in fact guilty, discrimination in legislative criminalization, in enforcement, and in sentencing practices are essentially unchallengeable.

Since Gideon, racial disproportionality in the prison population has increased. Not only might Gideon not have solved the problem, it may have exacerbated it. To the extent that Gideon improved the quality of counsel available to the poor, defense lawyers may be able to obtain favorable exercises of discretion in investigation, prosecution, and sentencing for indigent white defendants that they cannot for clients of color. For these reasons, racial disparity likely cannot be remedied indirectly with more or better lawyers. Instead, the remedy lies in directly prohibiting discrimination and having fewer crimes, fewer arrests, and fewer prosecutions.

Here’s a recent case of CJ Rice who was imprisoned for 12 years despite no physical evidence, no DNA, no gun and only a shaky photo array identification.

Shockingly, CJ’s overworked public defender never checked for his phone, which would have shown that he was halfway across town at the time of the shooting. He was also wounded from himself being shot and it was physically impossible for him to run away — as the suspect in this case had done.

During this broadcast, an attorney from the Exoneration Project stated that there were likely about 50,000 innocent people in our jails today. And I’d be willing to bet that most of them are Black.

The Exoneration Project is one of the best-funded, largest, and most successful innocence projects in the country. To prove our clients’ innocence, we provide free forensic testing, experts, investigative services, and an experienced litigation team to get our clients home where they belong. To date, we have exonerated close to 200 clients, liberating them to live their lives and enjoy their freedom.

Beyond assisting our clients with their claims of actual innocence in court, we also try to address the systemic problems in the criminal legal system that cause innocent people to be convicted of crimes they did not commit. To do so, we advocate for greater accountability in the justice system and have successfully sought mass exonerations. Additionally, we work to ensure our exonerees re-enter society with the supports they need to succeed.

Racial discrimination is literally built directly into the bones of the system. In many ways, it is rotten to its core.

Innocent men have been executed in this nation.

Since 1973, at least 196 people have been freed after evidence revealed that they were sentenced to die for crimes they did not commit. That’s more than one innocent person exonerated for every ten who have been executed.1 Wrongful convictions rob innocent people of decades of their lives, waste tax dollars, and retraumatize the victim’s family, while the people responsible remain unaccountable.

There are thousands, perhaps millions, of cases of wrongful arrest, wrongful conviction and overzealous prosecution on the books.

Defunding this system may not be the right way to go, but significant reforms are sorely needed. Defendants should not just be afforded the illusion of counsel, they need an effective, competent and properly funded defense that is equipped to counter the inherent flaws and mistakes that will continue to be made by law enforcement.

Unlike the refrain from Law and Order there are actually three branches of government that protect the public. And that third branch — Public Defender — is the one branch whose name actually states their single goal, Defending the Public.