The Civil Rights Movement and Kamala Harris’s Foreign Policy

Black Americans have always sought international connection in service of promoting freedom.

How might the U.S. civil rights movement inform a Harris administration’s approach to foreign policy?

How might the U.S. civil rights movement inform a Harris administration’s approach to foreign policy?

In a world riven by authoritarian leaders eager to capitalize on American divisions, such an approach would certainly be welcome. And the civil rights movement is arguably directly responsible for presidential candidate and current Vice President Kamala Harris’s existence: Her parents met in 1962 at a University of California, Berkeley campus study group where her father delivered a speech on the parallels between Jamaica and the United States.

While many Americans think of the civil rights movement as a distinctly U.S. phenomenon that began in the 1950s, in reality it began much earlier. Black Americans began pursuing civic equity through formal channels in the 19th century, and from the very beginning that pursuit was strategic in its international engagement. Harris’s parents—both raised as British colonial subjects in Jamaica (her father) and India (her mother)—saw the work of making the United States more equal as paramount to their lives. They engaged deeply with that work and imparted their dedication to their child. This story alone is emblematic of the global dimensions of the cause.

Long before the end of chattel slavery, though, Black Americans sought international connection in service of promoting freedom—for themselves and for others. In 1845–46, abolitionist Frederick Douglass made the first of his transnational lecture tours, spending 18 months in England, Ireland, and Scotland captivating audiences with his vivid depiction of slavery’s evils and urging them to support abolition. In Ireland, Douglass and Ireland’s Daniel “the Liberator” O’Connell crossed paths, with both speaking of the parallels in their peoples’ quests for liberation.

In their late 1880s tour of the Antipodes and Asia, the Fisk Jubilee Singers gave concerts as a means of raising funds for Fisk University’s mission to educate Black students. Director Frederick Loudin prefaced each performance with a brief talk about the importance of education to Black Americans and initiated outreach to indigenous people in the countries the group visited (such as the Maori in New Zealand and the Karen in Myanmar). The Fisk singers thus acted as people-to-people diplomats, and in his writings, Loudin presented the tour (and the resulting economic benefits for the university and the members of the troupe) as part of the effort to solve what was then referred to as the “Negro Problem.”

In the 1890s, journalist Ida B. Wells used public lectures to British audiences similarly—to highlight the vicious cruelty of lynching of Black men in the United States. The charismatic and incisive force that both Douglass and Wells brought to bear on the international stage served to leverage shame abroad against the egregious situation facing Black Americans.

Several years later, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 sparked collaborations between many activists in the United States and those abroad. Japan’s defeat of Russia, which was widely covered in the Black press, prompted Black American intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois to consider the implications for white colonial powers in the Caribbean and Africa. During the post-World War I period, Black American experiences were seen as directly relevant to the aspirations of Asian nations seeking to emerge from European (and U.S.) imperialist influences. Indeed, between 1919 and 1941, Black Americans engaged with Asia across a wide range of endeavors: journalistic, artistic, religious, diplomatic, and others. And despite the many constraints facing them, Black women specifically engaged with internationalism in creative and vital ways.

In fact, one of the most powerful tools deployed in the 20th-century iteration of the U.S. civil rights movement—nonviolent direct action—grew directly out of international connection: Black American and Indian exchanges around a common desire for liberation from racial oppression. That connection is commonly thought of as beginning with Martin Luther King Jr.’s deployment of Gandhian nonviolent direct action approaches in the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott of 1955. In reality, the connection’s early roots began decades earlier. During the late 1920s, Black American writers and religious leaders began to study Mahatma Gandhi’s work in India. African American educator Juliette Derricotte was among the earliest Black Americans to travel to India and return to lecture to Black audiences on Gandhian thought.

Seven years after Derricotte’s trip to Mysore, India, theologian, pastor, and educator Howard Thurman went to South Asia as leader of a “Pilgrimage of Friendship.” Thurman and the other members of the group took on extensive speaking and meeting obligations over 140 days in India, Myanmar (then Burma), and Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in late 1935 and early 1936. Most vitally, Thurman and Gandhi had a three-hour meeting that catalyzed deep reflection in Thurman. The encounter resulted in writings and mentorship efforts by Thurman that fostered and inspired operational geniuses of the United States’ modern civil rights movement, such as Pauli Murray, Bayard Rustin, and James Farmer.

Against that backdrop, is it any wonder that Harris’s parents—two bright and inquisitive young people from British colonies in the Caribbean and Asia—would find resonance in the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s?

In 1964, the year Harris was born, the United States was undergoing a number of significant political developments. The movement for civil rights freedom was shifting from a perceived “Southern problem” to the center of the national stage. Activists in the San Francisco Bay Area were making significant strides. On the UC Berkeley campus, college students joined forces with local civil rights groups to condemn racism and discrimination. Then-doctoral students, Harris’s parents were deeply moved by these developments. They held meetings with civil rights leaders at their home and even organized a weekly reading group to grapple with core texts on civil rights, anti-colonialism, and global Black politics.

Despite the successful adoption of the 1964 Civil Rights Act under then-President Lyndon B. Johnson’s leadership, segregationists still had a grasp of the Southern state parties. In response to Mississippi’s refusal to allow Black citizens to participate in elections, civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer and other activists established the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. At the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Hamer advocated for the recognition of the party. A nationally televised broadcast shared Hamer’s riveting testimony to the convention’s credentials committee of vicious beatings and threats from white supremacists who hoped to prevent her from registering to vote. “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America,” she argued.

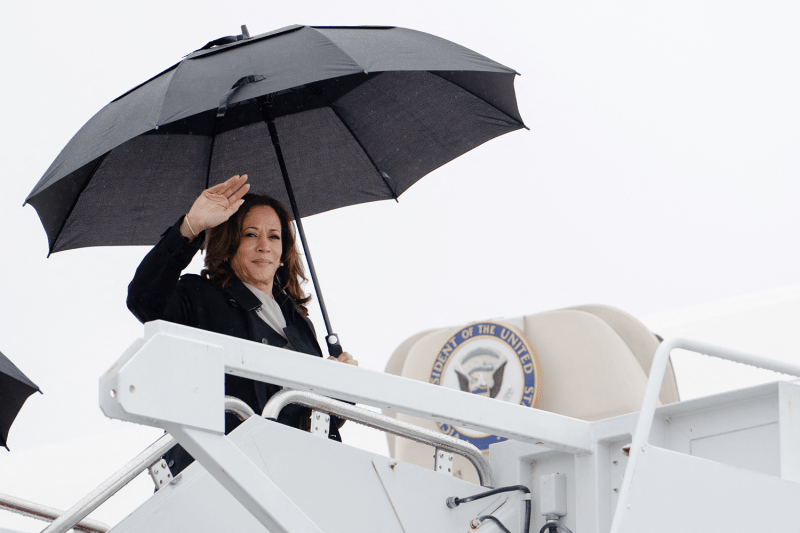

Sixty years after Hamer’s powerful testimony, Harris, a biracial female politician, is the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, poised to become the first woman of color at the top of a major political party ticket. The Black freedom struggle in the United States and its global connections accentuate two vital points: the inherent dignity of each human being and the importance of freedom for all. These basic, yet profound, ideals were at the core of the U.S. civil rights movement and will no doubt inform Harris’s political vision.

Indeed, the first video launched by the Harris campaign uses freedom as its central message (to the stirring Beyonce song of the same name). A frequently invoked quote of Harris’s—the search for “what can be, unburdened by what has been”—reflects the described understandings. Courageous freedom fighters including Hamer, Wells, Douglass, Thurman, Murray, and many others paved the way for this moment. These activists crossed geographical boundaries to garner widespread support for the long fight of the civil rights movement. They defied many challenges in an effort to realize the ideals of human dignity and autonomy for all people. Surely their vision will help inform a Harris administration’s approach to foreign policy.

Keisha N. Blain is a professor of Africana studies and history at Brown University.

Amy Sommers is an author and attorney.

More from Foreign Policy

The Top International Relations Schools of 2024, Ranked

An insider’s guide to the world’s best programs—for both policy and academic careers.

Harris and Walz Can Remake U.S. Foreign Policy

The VP pick may help Harris reinvest in diplomacy—and abandon America’s reflex for military interventionism.

The Two Biggest Global Trends Are at War

World leaders will have to learn to navigate the contradictions of the new world order.

Ukraine’s Invasion of Russia Could Bring a Quicker End to the War

One aim of the surprise breakthrough may be for Kyiv to gain leverage in negotiations.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out