Three years after the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis kicked off a wave of protests about racial inequality, financial institutions are still reckoning with their past.

Lloyd’s of London, the world’s largest insurance market, is preparing to reject the case to pay direct reparations to the descendants of slaves whose transport it insured, it emerged last week.

After conducting research to better understand its role in the slave trade with Johns Hopkins University in the US, Lloyd’s is instead preparing to fund diversity initiatives aimed at tackling racial inequality.

It is understood that Lloyd’s has struggled to identify who would directly receive reparations. An update is expected soon.

However, such a move could set the insurer up for a clash with Caribbean nations and interest groups who are calling for direct transfers to the descendants of slaves, rather than investment in broader support schemes.

It is understood that formal letters are being prepared by national reparations commissions in the Caribbean to put the case to institutions including Lloyd’s of London by the end of the year.

Is the City doing enough to confront its slave-sponsoring past?

Despite happening more than 4,000 miles away, George Floyd’s death had significant reverberations across the Square Mile. A conversation about racial justice ignited debate over the City’s role in financing, facilitating and benefitting from the international slave trade. The long history of the area’s most storied institutions meant several had direct links.

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 had significant reverberations around the world

Credit: Victoria Jones/PA

Insurance marketplace Lloyd’s of London, which grew out of the coffee houses of 17th-century London, and the Bank of England, founded in 1694, subsequently apologised for their “shameful” and “inexcusable” roles in the Atlantic slave trade.

At the time, Hilary Beckles, chairman of the Caricom (Caribbean Community) Reparations Commission, which was set up by Caribbean nations to seek reparations from former colonial powers such as the UK, said: “It is not enough to say sorry.”

Reparations commissions are pushing for direct financial transfers, rather than words, exhibitions and investment in broader schemes aimed at improving opportunities for those affected by the legacy of colonialism.

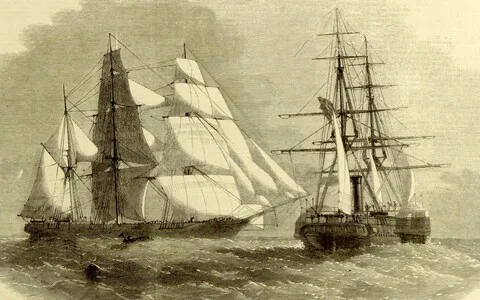

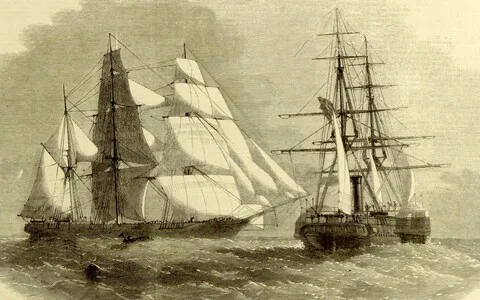

Lloyd’s ties to the slave trade date back to 17th century. It is estimated that between 1640 and the early 19th century, more than three million enslaved African people were transported by Britain’s shipping industry. Lloyd’s was the global centre for insuring that industry and underwrote enslaved people as part of a ship’s cargo.

It took until Floyd’s death in 2020 to prompt a “journey of reflection” at the insurance market. At the time, Lloyd’s said it wanted to acknowledge this “appalling and shameful period of English history, as well as our own”.

It added: “Lloyd’s is on a journey of research and reflection as we acknowledge our historical connections to slavery, as well as the lack of ethnic representation – particularly at senior levels – that still exists within the Lloyd’s market.

“While slavery’s connections to Lloyd’s history have been tacitly acknowledged before, they have never been fully interrogated or accounted for, until now.”

Statements such as these hold little truck with many Caribbean countries, who argue their inhabitants are still feeling the economic legacy of slavery.

Lloyd’s of London insured many of the ships that transported enslaved African people between 1640 and the early 1800s

Lloyd’s is not the only City institution that could come under pressure to hand out direct compensation. Others with historical links to the slave trade include the Bank of England, Barclays, Lloyds Banking Group and NatWest, formerly known as Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).

All have issued apologies in the past regarding links to the slave trade, whether through financing or the slave ownership of their directors.

In RBS’ case, a 2009 report funded by the bank found evidence that individuals “who were partners or directors of RBSG predecessors may have owned slaves themselves or been otherwise directly connected to slave enterprises in the British West Indies”.

The Bank of England, which is currently running a “Slavery & the Bank” exhibition in its museum, has apologised for the involvement of some of its past governors and directors in the slave trade.

In 2021, it also removed 10 oil paintings and busts of seven governors and directors who had known connections to the slave trade.

Yet few institutions have addressed the issue of reparations directly.

Earlier this year, a Barbados ambassador said that the central bank was among British institutions that needed to finance “a concrete programme of reparations”.

David Comissiong, Barbados’ ambassador to Caricom, said: “The eyes of all right-thinking people, all over the world, will now be on the British government, the British royal family, the Bank of England and other institutions of the British establishment, and the governments of Spain and other relevant European countries.

“How will each of them respond to the moral imperative that now confronts them? The world will be watching.”

A spokesman for the Bank of England said the payment of reparations was a subject for the Government rather than Threadneedle Street.

Former BBC journalist Laura Trevelyan gave £100,000 to Grenada as compensation for her family’s ancestral slave holdings

Credit: David Levenson/Getty Images Europe

However, there has been a recent shift in focus from Caribbean nations to seek institutional reparations rather than pursue government agreements.

This has, in part, been influenced by Laura Trevelyan, a former BBC journalist who has given £100,000 to Grenada as compensation for her family’s ancestral slave holdings.

More than 100 wealthy British families who are descendants of plantation owners have now signed up to Trevelyan’s “Heirs of Slavery” initiative to pay reparations to help Caribbean countries.

Arley Gill, the chairman of Grenada’s reparations commission, previously told The Telegraph that the duty to offer reparations lay at the door of institutions that benefited from the slave trade such as banks and Lloyd’s.

So far, institutions appear reluctant. In part, this is likely to reflect the difficulty of identifying who exactly would qualify and the somewhat gruesome accounting involved in deciding how much reparations to pay.

Lloyd’s of London is set to provide further details next month about its role in the slave trade and what initiatives it will fund to atone for its past.

Whatever the details, it is unlikely to put the conversation about reparations and the City’s links to slavery to rest.