As mental health issues worsen for Americans at large, the African Diaspora tries to bridge the gap by promoting the 988 suicide and crisis lifeline.

The past few years have been rough on Black folks. The pandemic shut down the nation. People lost jobs, income and loved ones to COVID 19 variants or complications. Also, poverty and food insecurity soared, education was disrupted, fear of what the future holds, and a big dose of overt 1950s-era racism resulted in spiked depression and anxiety rates throughout Diasporic communities.

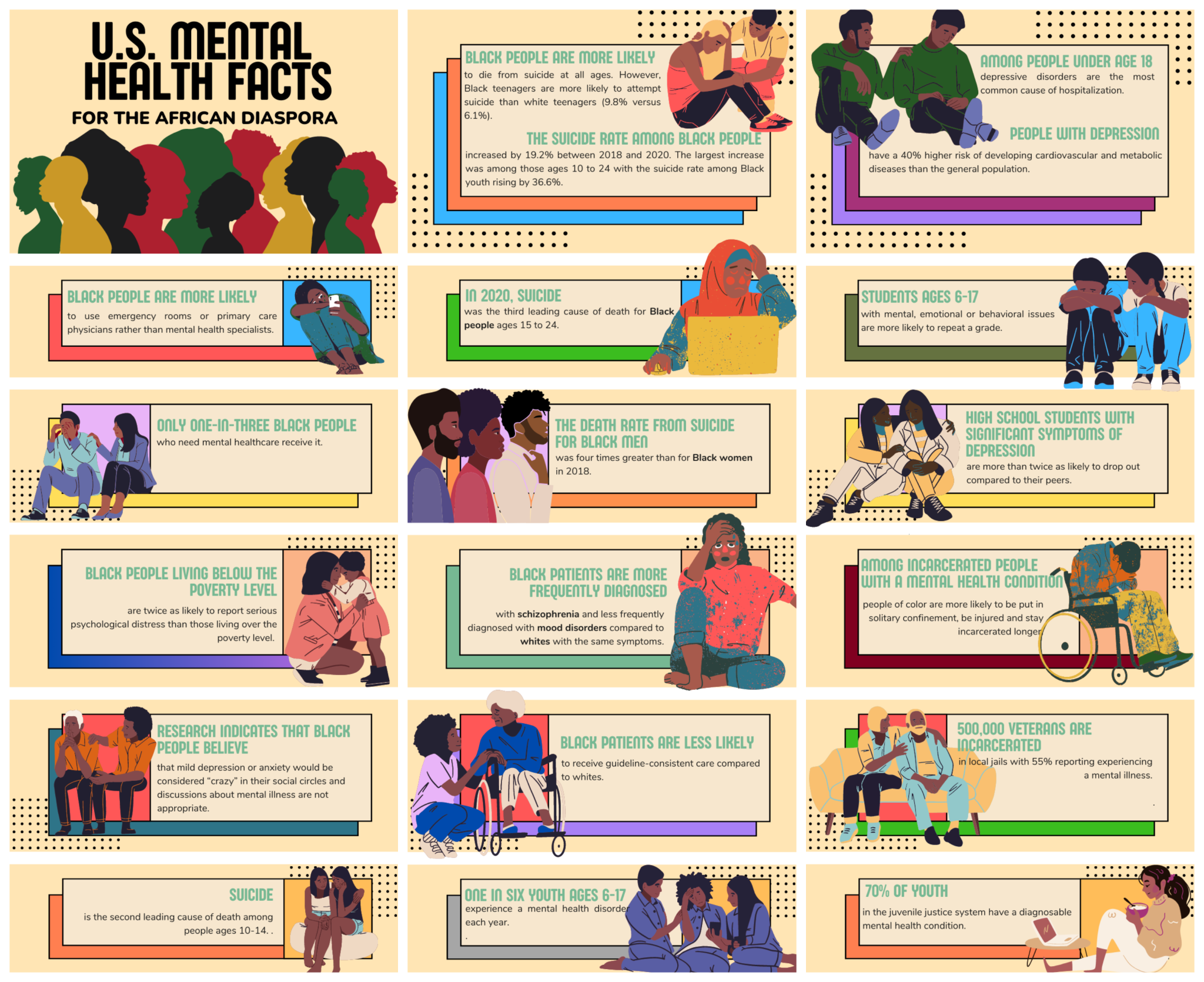

In fact, a recently released U.S. Preventive Services Task Force report found that anxiety disorders are the most common mental illnesses, impacting 40 million American adults each year. The group of 16 independent medical experts also purported that Black people have a higher risk of said disorders due to social factors including racism, rather than genetics; with issues beyond the stress of the pandemic. In many cases, stemming from generational trauma and violence. Notably, having impacts on the emotional and mental health of both youth along with adults as compared to their white counterparts.

Despite progress made over the years, racism continues to have a negative impact on the mental and physical health of Black people. Socioeconomic status is linked to mental health. Impoverished people are at higher risk for poor mental health. Simply put, being stressed and depressed are often the result of being oppressed.

“African Americans have been traumatized, victimized and oppressed since arriving in the U.S.,” stated Sheila Bennett, a retired social worker. “Conceivably, mental health therapy could help resolve and address these issues. While therapeutic counseling has been an option available, the magnitude of African-American providers of this service is quite inadequate.”

From a horrific African Holocaust to today’s more tame attacks, usually in the form of microaggressions, are both overt and covert acts of racism still plague Black thought. In response on the federal level, Congress officially recognized July as “Bebe Moore Campbell National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month” in 2008.

Importantly, Campbell was one of the founding members of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) – Urban Los Angeles. Born and raised in Philadelphia, the late award-winning African American writer dedicated much of her work to addressing the impact of racism on mental health, culture and community. She challenged the status quo and shed light on the unique struggles faced by people of color.

Initially, Campbell’s family members suffered from mental illness and recognized the consequences of the stigma. Currently her daughter, the actress Maia Campbell, has been open about her battles with bipolar disorder. According to NAMI, one in five adults experience mental illness each year– and over 20 percent of them are Black.

The 988 Diaspora Campaign continues the late author’s work by promoting awareness of the federal 988 Mental Health Lifeline.

Yet, much remains especially in light of the cataclysmic effects of the past three years. Stigmas and other issues often prevent people of African descent specifically from seeking treatment for their mental illness. That is why the popular Philadelphia-based Fun Times Magazine initiated the “988 Diaspora Campaign” to move “the African Diaspora to positive, affirmative action regarding their mental health,” explained Eric Nzeribe, FunTimes publisher. As well as to promote awareness and use of the federal 988 Mental Health Lifeline.

The campaign focuses on building a network of Black mental health professionals, community leaders and organizations to educate members of the African Diaspora–African American, African, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino–in the Philadelphia Region on the importance of mental health treatment. The campaign is funded by the Knight-Lenfest Local News Transformation Fund.

“We especially want to engage local Black mental health professionals that can speak to the public on issues that specifically affect the mental health of people of African descent,” Nzeribe said.

As a result of the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act passed by Congress in 2020, the initiative was officially launched in 2022 and was modeled after the traditional 911-system. So, people who call or text The 988 Lifeline will be connected to local call centers staffed by mental health professionals.

The 988 Lifeline is also being promoted as an alternative to 9-1-1 when someone is experiencing a mental health crisis, which often has negative results for Black people when the police arrive. “Our campaign wants to get out the message that if you or a loved one are angry, stressed, depressed, anxious or going through a mental health crisis, don’t call the police. Call, chat or text 988 instead,” said Nzeribe.

The 988 Lifeline is free, anonymous and available 24/7.

⚈ ⚈ ⚈ ⚈

According to the American Psychiatric Association, other barriers to Black patients include disparities like poor quality of care and lack access to culturally-competent care compared to the general population. Also, they are less likely to be offered evidence-based medication therapy or psychotherapy.

Moreover, differences in how Black patients express symptoms of emotional distress may contribute to misdiagnosis. Physician-patient communication differs for Black and white patients. One study found that physicians were 23 percent more verbally dominant and engaged in 33 percent less patient-centered communication with Black patients than with white patients.

Making sure the diaspora gets the care they need and deserve is the bottom line. Hence, The 988 Campaign was also developed in hopes of being a trusted listing of local culturally-competent mental healthcare providers in addition to promoting use of the 988 Lifeline. Chiefly, properly gearing Black mental health professionals to provide patients of color with access to culturally-competent therapists. Especially seeing as trust-building is integral in an effective, sustainable medical relationship and ultimately, long-term success. An ironic predicament between the white majority and formerly enslaved, yet still highly discriminated against African-American.

“It’s like going to the perpetrator of a crime and asking for help with your most sensitive life matters,” explained Bennett. Indeed, enslavement, Reconstruction, government-sanctioned Jim Crow segregation, and the Civil Rights era into the Prison-Industrial Complex has more than helped exacerbate matters. “There’s a comfort in confiding in someone who can empathize, which makes for more effective processes. This usually comes with the territory in Black-on-Black therapy.”

“We want to make sure our people are well-received and respected by healthcare providers,” said Nzeribe, leaving room for a silver-lining: “Hopefully, this will encourage people to seek the care they need.”