- Reverend Earle Fisher launched a petition against a Tennessee bill banning the study of reparations

- In just two days, the Memphis pastor’s petition amassed more than 500 signatures from other Tennesseans

- State Senator Brent Taylor, who sponsored the bill, said that reparations should be handled by the federal- not local- government

Tennessee has found itself riven by a bill in the state senate that would forbid the study of reparations for the descendants of slaves.

The bill, which will be voted on in the House next Wednesday, has created some blowback in the state.

Chief among the bill’s critics is Reverend Earle Fisher, the senior pastor of Abyssian Baptist Church.

This week, the Memphis pastor launched a petition against the bill, and in just two days, it amassed more than 500 signatures.

Speaking to NewsNation, Reverend Fisher said that the decision to axe any future studies of reparations was not motivated by a desire to save money.

‘This is not about money. This is about ideology. This is about political power,’ Fisher said.

He continued: ‘This is about people who are hell-bent on maintaining racial and economic inequities across the state and they are scared to death that the truth would come out. So, they don’t want anybody to study it’.

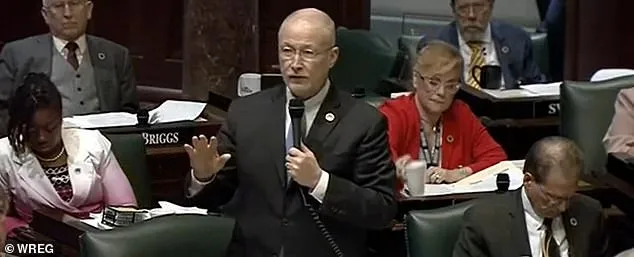

State Senator Brent Taylor, a Republican representative from Shelby County and a sponsor of the bill, has argued that reparations should not be addressed at the local level.

Senator Taylor believes that the matter of reparations should be resolved on the national stage, and that it is not within the ability of a local government to remedy such a large issue.

‘I will make very clear our vote today does not pass judgment on reparations. That is a very significant and very important issue for many people in our country,’ Taylor said.

He continued by saying that the issue of reparations ‘belongs to the federal government and does not belong to our cities and counties’.

‘I think it’s inappropriate for our cities and counties tax dollars to go to such an issue,’ Taylor said.

Amendment No. 1, which was added to the bill and passed in the Senate a year ago, is the source of the controversy.

It states that it ‘rewrites this bill to prohibit a county, municipality, or metropolitan government from expending funds for the purposes of studying or disbursing reparations’.

The amendment defines ‘reparations’ as ‘money or benefits provided to individuals who are the descendants of persons who were enslaved’.

Reverend Fisher insists that if the state has a budgetary surplus, they should use that money for a worthy cause, like the study of reparations.

‘If the state of Tennessee has hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars in a surplus, surplus means we are taking care of all of our financial responsibilities, and this is how much money we have left over. We can even call it expendable income,’ Fisher said.

‘There are other entities and organizations that get 25 times that to do something most of us will probably say is a lot less significant’.

Last year, commissioners of the Tennessee county that includes Memphis voted to launch a feasibility study to examine reparations for the descendants of slaves.

The Shelby County Board of Commissioners voted on the measure, which allocated $5 million to fund a feasibility study to ‘establish, develop, and implement reparations’.

All eight black members of the commission voted in favor of the measure, while the five white members all voted against it or abstained, citing financial concerns about the $5 million allocation.

The reparations study, which was only one of many similar other studies conducted across the US, came a month after black police officers killed Tyre Nichols, a black man, in Memphis.

Nichols’ death was referenced in by many of those in favor of the reparations study, including Commissioner Miska Clay Bibbs, who said: ‘My people are dying on the daily. That’s why I support this’.

‘It’s clear something has to be done. That’s all this resolution is trying to do is saying we have to address what’s happening in Shelby County in a different way,’ Bibbs said.

The commissioners who opposed the measure cited budget constraints, legal concerns, and fears that it would prove divisive in the community.

‘I just don’t think this is the best way to move the community forward in a unified manner, and that is my reasoning, as well as the financial piece,’ said Commissioner Brandon Morrison, who voted ‘no’.

Before calling the vote, Commission Chair Mickell Lowrey addressed his colleagues, saying: ‘Commissioners, it’s ok to disagree. We all represent different communities, and we’re supposed to disagree, our constituents don’t all have the same issues or concerns’.

‘Our diversity makes us better, so I appreciate all the comments, and respect all of them,’ he added.

The population of Shelby County is about 52% black, 41% white, 6% Hispanic and 2% Asian, according to county government data.

The resolution on the reparations study that passed directed the state to examine five areas: access to affordable housing and homeownership, affordable healthcare, systemic disenfranchisement in the criminal justice system, career opportunities, and financial literacy and generational wealth.

The resolution used the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America’s definition of ‘reparations’.

They defined reparations as ‘a process of repairing, healing, and restoring a people injured because of their group identity and in violation of their fundamental human rights by governments, corporations, institutions and families’.

Last year, Shelby County was only one of several cities to consider reparations for slavery, a topic that proved divisive in many areas.

Other places like Boston, Massachusetts, St Paul, Minnesota, and St Louis, Missouri, as well as the California cities, San Francisco and Los Angeles, all set up task forces and panels to hatch their own reparations plans.

But this year, the push for reparations appears to have lost some of its momentum.

Squad member Cori Bush, the Missouri Democrat who has championed payouts, is under investigation for campaign spending violations.

Her bid for a $14 trillion federal compensation package is dead in the water.

The reparations task force in Detroit — a hub for African-American culture — has descended into a ‘shambles’ of quitting and in-fighting.

And in February, California’s black lawmakers backtracked on plans to pay $1.2 million to each resident.

While many black voters are keen to get checks in the mail, only a fraction think they’ll see such a day in their lifetimes.

Mike Gonzalez, an analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation, said support for reparations peaked amid the protests over the police killing of George Floyd in 2020.

Now, it is waning, he added.

‘Like diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), Critical Race Theory, anti-racism trainings, and other features of the collective hysteria, the call for reparations has begun to fall apart under intense opposition by the American people,’ he told DailyMail.com.