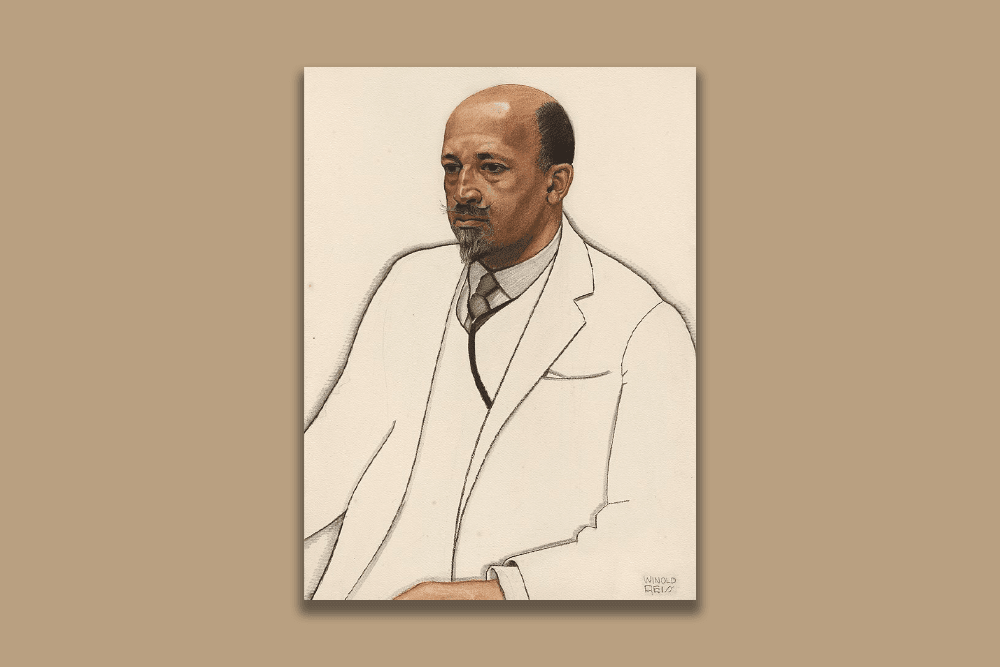

This year marks 60 years since the death of W.E.B. Du Bois, who lived from 1868-1963. We remember the late sociologist, educator, socialist activist, NAACP co-founder, and revolutionary academic for his work in resisting racial capitalism in the classroom, the streets, and the Black church.

I first encountered Du Bois in middle school in an old biography — its pages falling apart, its cover hanging on by a thread. The writing was just dense enough to offer me a challenge but not so difficult that I couldn’t understand it. Ultimately, it provided the intellectual and vocational awakening I needed. In reading about Du Bois’ life, I was struck by his ability to use his academic prowess as a vehicle for the liberation of his people, as well as the way he carried himself as a Black man: DuBois was well-dressed, sharp-tongued, and articulate; he left no room for his colleagues to question his intellect or his commitments to his community.

As a Black kid growing up on the West Side of Chicago — a culturally vibrant conglomerate of predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods that has experienced years of disinvestment from the city’s powerbrokers — I learned about Black radical politics through Du Bois’s work, including how disinvestment could result in decades of community and police violence. He also reminded me that I could use my intellect to serve my community which deserved infinitely better than what we were receiving under the system of racial capitalism.

As I developed into a public theologian for my community, I began to realize the sheer impact of Du Bois’ work beyond the realm of Black radical politics. While Du Bois was not a trained theologian and remained deeply unsure about God throughout his life, his work still has much to offer the world of Christianity.

In Du Bois’ The Negro Church, he intentionally centers the African American religious experience as the focal point of Black resistance to white racism. In his Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois refers to the inner quest for freedom among Black people as a “spiritual striving.”

I not only found inspiration for Du Bois’ intellectual accomplishments but was also spiritually fed by the ways in which Black theologians engaged with him as a conversation partner, incorporating some of his central ideas into their own works and analyses.

In a 1985 essay, the theologian James H. Cone, claimed that Du Bois’ theory of the “double-consciousness” of Black identity has been “at the center of Black religious thought from its origin to the present day.” Cone, a key founder of Black liberation theology, would later use Du Boisian ideas concerning the centrality of a person’s social context when analyzing race, the unique spiritual nature of Black identity, and the enormous and essential task of eradicating racial capitalism in his Black Theology & Black Power (1969), A Black Theology of Liberation (1970), and God of the Oppressed (1975).

Neither Black academic nor theological spaces fully grasp Du Bois’ relevance; his work is seldom a point of reference in Black churches. Much of this is due to Du Bois’ complex relationship with religion in general and Christianity specifically. As a professor at Wilberforce University, a Methodist-affiliated Black college, he refused to lead public prayer or participate in public worship. Du Bois resented the church’s dogmatic claims, believing that the white church’s complicity in racism and the perceived anti-intellectualism in Black churches ultimately made these institutions harmful. And yet, Du Bois harbored a certain respect for the Black church’s liberating spiritual components and the use of religious belief for social transformation.

Du Bois’ impact on mainstream American studies on race, class conflict, politics, and sociology is similarly overlooked: Though Du Bois has been called the “founder of modern sociology,” most scholars ignored him during his active years, and he is still marginalized today.

When it comes to the tension between Du Bois’ work and the church, we must resist the urge to rectify this tension posthumously. Instead, we can use Du Bois’ complicated feelings toward American Christianity as a tool to critique churches that are far too often married to powerful and oppressive forces.

For Black Christian thinkers like me, Du Bois’ work in analyzing the social dimensions of Black religion and racial capitalism helps ensure our theology is grounded in a constructive framework for liberation, not passive resistance to oppression.

Du Bois rightly criticized incremental change and Black capitalism in Souls of Black Folk, reserving his harshest words for author and activist Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), whose “Atlanta Compromise” speech promoted Black individualism instead of racial equality and an end to segregation. Du Bois labeled this as a “submission” to white power. How poignant and timely is this sharp criticism of capitalism for us today, as corporate America seeks to pacify Black Americans with an alluring assimilationist framework aimed at “representation” rather than equitable pay, fair working conditions, strong labor unions, and pensions?

Why is it that powerbrokers — Black, white, or otherwise — continue to give us the appearance of change when what working class people of all races actually want is material change?

The only way we will be able to live up to Du Bois’ legacy is by combining the wisdom of our ancestors with the audacious sense of justice that burns within each of us to create a world where we are all free. Our ability to name America’s ills as social ills, to be vigilant in the face of marginalization, to resist the restraining hierarchies of unjust institutions — all of these things Du Bois did in his own lifetime. It’s critical we continue on this path if we are to build a more just world.

We must rise to the occasion, resist the temptation to accept half-measures for freedom, and fight for total freedom; the realization of a more just society that Du Bois spoke of — in our churches, our seminaries, and our communities. If nothing else, our Christian faith must echo the words Du Bois used to describe his own mission, “I am one who tells the truth and exposes evil and seeks with Beauty for Beauty to set the world right.”