THE STIGMA around mental health in the Black community has long been an issue that prevents those who need it from getting vital treatment.

But new figures from The Voice’s Black British Voices (BBV) survey reveals a major shift in the way that people of African Caribbean origin view mental health compared to previous generations.

According to the data, modern-day Black Britons feel there needs to be more openness and honest conversations about the issue.

Young Black people, particularly members of Generation Z, are more likely to seek help from mental health professionals compared to earlier generations who felt they had no choice but to cope without complaining or risk being seen as ‘weak’.

The BBV research found that nearly 70 percent of those questioned said they or members of their family had battled with mental health issues.

However, marking an important change, 87 percent of respondents felt that mental health was not discussed enough in the home – indicating a desire to tackle the stigma that prevents people from talking about the issue.

One person who was interviewed as part of the study said: “When we grew up, we never used to see our parents complain. They’ll just take it on the chin, like slavery. So I feel like it’s just embedded in us. But I feel like we need to actually speak up about it and make sure things are going a different way.”

A number of factors have contributed to this greater willingness to talk about mental health. Black celebrities have played a key role.

In recent years high-profile figures such as Jay-Z and Michelle Obama have opened up about their struggles with mental health and encouraged those struggling to get help.

In November 2017 former world heavyweight boxing champion Frank Bruno won several plaudits following an exclusive interview with The Voice in which he highlighted his battle with mental illness, the impact it had on his family and his road back to health.

Hashtags like #BlackMentalHealthMatters have helped to create safe spaces for opening up discussions.

Ariel Breaux-Torres, Head of Race Equity at Mind, said: “Platforms like Tiktok, and Instagram have really boosted openness around the issue and definitely helped to open conversations about mental health.”

Social media is a key tool for R’n’B singer JayJayBorn2Sing who uses his music to raise awareness about mental health issues.

Earlier this year he wrote and released a single called ‘Champion’ after a traumatic period in his life.

He said: “Someone very close to me made three suicide attempts. I’ve also had my fair share of battles in terms of suicidal thoughts.

“My life hasn’t been the greatest. So I was writing the song about myself and about my friend. The day after I recorded it another close friend of mine died.

“I needed to express how I felt through the song. Many of us who’ve grown up in the Black community have been taught to suppress emotions.

“Champion’ challenges the perception of suicide as weakness, and the tendency we have in the Black community to not talk about these issues.

“I wanted to acknowledge those who’ve survived suicide as champions because they’re still here, still carrying on. It celebrates their resilience and courage despite their mental health struggles.”

He continues: “When I released the track on Instagram and other social media platforms the response was phenomenal. People started posting their own videos in response, explaining why they too were champions.”

However, although Black Britons now talk more openly about mental health compared to earlier generations, stigma around the issue remains.

More than two-thirds (68 percent) of those polled confirmed that either they or a member of their family had struggled with mental health issues.

One interviewee highlighted the issue by speaking about his father who went through traumatic experiences growing up as a Black man in 1960s Britain.

“My dad doesn’t really talk about it (mental health). I look at him and think here’s a Black man who lives on his own in his mid-50s, and I reflect on some of the conversations we’ve had together, and it’s clear that he’s got something going on.

“The stories he tells me, I’m like, ‘you should really talk to someone at some point Dad!’ But I know he would never say a word.”

Another BBV participant said: “People used to laugh and say ‘Black people don’t have mental health problems, that’s a white people thing, we can just tough it out.’”

The reasons behind the high numbers of Black people experiencing mental ill-health are complex but a growing body of other research points to the substantial psychological toll of everyday racism.

Mental health problems are also more likely to occur among people who are struggling financially or living in poverty.

When racism is added to these other societal factors such as poor housing or school exclusions it can have a major impact on mental health.

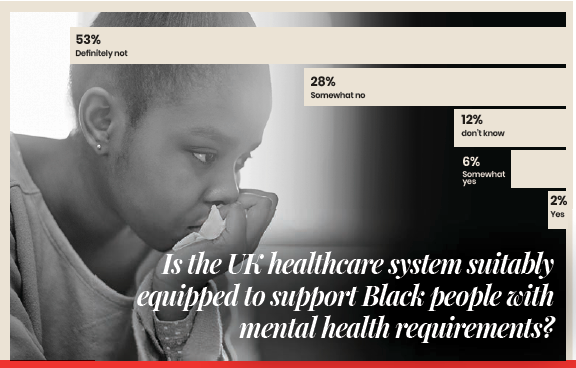

Our research found that 81 percent of BBV participants felt that the mental health system was inadequate for the community’s needs.

Despite facing higher rates of severe mental health diagnoses Black people, especially men, often avoid seeking help due to a historical mistrust of the system, which has a record of misdiagnosis among Black patients.

88 percent of BBV survey respondents answered either ‘definitely’ or ‘somewhat’ yes when asked the question of whether they ‘feel there is a problem with misdiagnosis, over-medication, or unfair treatment towards Black people in the provision of mental health care in the UK.

The high-profile deaths in police custody cases of Kingsley Burell-Brown, Sean Rigg, Olaseni Lewis, Colin Holt, Mikey Powell and Roger Sylvester – who were all suffering mental ill-health – have reinforced the view that mental health struggles will be met with force rather than treatment.

Since the tragic death of David ‘Rocky’ Bennett in 1998, which led to a public inquiry in 2004, it seems as though little has changed for Black people in the mental health system.

NHS mental health services have also been slow to adopt culturally competent mental health care, something that campaigners have long called for.

Author and mental health therapist Jarell Bempong, who recently published the book ‘White Talking Therapy Can’t Think in Black’ says that diverse, tailored approaches are essential to delivering culturally competent care and addressing inequalities in service delivery.

“White-led talking therapy often fails Black people because the people delivering it often lack cultural empathy due to societal power dynamics and privilege.

“I struggled to find a therapist who understood my cultural experiences. This leads many Black individuals to only ever accessing mental health treatment through the criminal justice system, resulting in worse outcomes.”

Bempong continues: “Modern psychology was shaped in an era of white supremacy, neglecting Black experiences. We need to integrate culturally relevant approaches to make therapy inclusive and relevant for Black and minority people.”

Cultural Healing

Many organisations have been launched during the past decade to support Black people who are experiencing mental ill-health with culturally-competent care.

One such organisation is the Black Health Initiative, a charity in Leeds which emphasises what it calls cultural intimacy as a way of helping to create a space where people can open up.

The chief executive Heather Nelson said: “Our service users say that when they come to a Black counsellor, they don’t have to explain mannerisms.

“So, for example, if a Black person kisses their teeth, we wouldn’t be asking for an interpretation of that because culturally we are aware of what that means.

“At group discussions, we’ll always have Caribbean food. We’ll have music such as reggae or RnB. It sounds really simple but when people are in crisis music and food can be very soothing.

“They can be symbols of something familiar, a connection to happier times, which can be important to a person’s recovery.

“A big part of the group discussions is asking people what they do to cope when they’re feeling unwell. Some are honest and say they’ll smoke a spliff.

“Others might tell the group how they play squash. I’ve heard the discussions where someone will come and say ‘what you doing with squash? It’s a white man’s sport.’ But before you know it peer support, and sharing of ideas to support recovery, is happening right in front of them.”