A commission appointed to study possible reparations to Black people in Kansas City faces a big hurdle before its first community listening session on Saturday.

Funding.

The Mayor’s Commission on Reparations was established earlier this year without any money to do the work that its 13 members seek to do.

Their primary role is to document racial harms — and to do so with a vigor that can stand up to possible legal challenges.

The commissioners will be studying Kansas City’s role as a municipality, and what it can be held accountable for in how anti-Blackness — codified in law or woven into public policy — has disadvantaged Black residents.

The scope is broad, ranging from the Civil War to the present day.

But the commission can only suggest recommendations and address who might be eligible after the harms have been thoroughly researched.

Put simply, reparations are a process. And Kansas City is at the beginning.

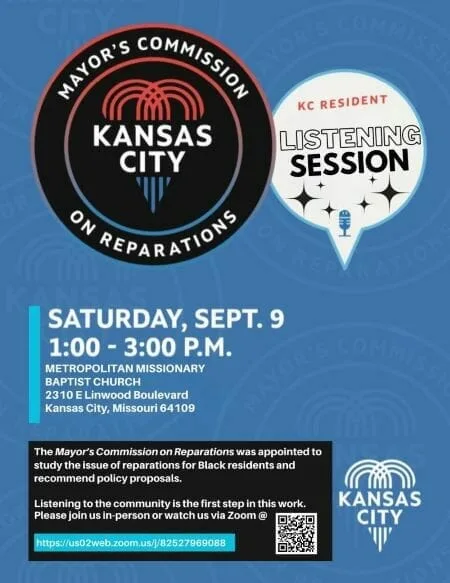

Community members are encouraged to attend the Saturday, Sept. 9, listening session from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. at Metropolitan Missionary Baptist Church, 2310 E. Linwood Blvd.

Terri E. Barnes, chair of the reparations commission, said a budget for the effort is being developed.

Barnes made the comment during the August meeting of an aligned, but separate group that pre-dated the city’s work, the Kansas City Reparations Coalition. The coalition formed out of work done by the National Black United Front-Kansas City, beginning in 2020, creating the groundwork for the city’s commission.

“Our priority is understanding the cost to do the work,” Barnes said during the gathering, held over Zoom. “Once we have a budget, we do have philanthropic organizations that have expressed interest.”

Barnes also is a founder and president of The Nia Project, which supports the success of Black girls and women.

Members of the city’s reparations commission were sworn in in May and given an 18-month timeline. They are expected to issue a report at the end of the first year, looking into a wide range of categories such as economics, health, homeownership, criminal justice and educational outcomes. They are expected to assess the city’s role within each topic, showing if Black Kansas Citians were disparately affected.

A final report, possibly with recommendations for redress, would be completed after an additional six months.

Janay Reliford, chair of the coalition, said that it is important that the public stay engaged, including supporting finding adequate funding for the research.

“When the coalition first began our work to get the commission seated, Mayor Quinton Lucas made a commitment to help secure funding for his commission,” Reliford said. “So, I would encourage residents to talk to the mayor about what’s going on with the commission and his funding.”

Asking local religious groups for funding has also been suggested through various faith’s social justice arms.

The KC coalition received a $2,500 grant from FirstRepair, an Illinois-based organization headed by the former Evanston alderwoman Robin Rue Simmons, who helped lead that city to approve the nation’s first government-funded reparations program.

Reliford said the funds will be used to host a 2024 showing of the PBS documentary “The Big Payback,” which chronicled Simmons’ efforts, and to hold think tank sessions for residents to share ideas on remedies for the injury areas identified by the city.

“We were able to get a community engagement award from them and they’re going to help us with some strategic planning,” Reliford said.

In a previous visit the Kansas City for a town hall sponsored by Kansas City PBS and American Public Square, Simmons stressed the importance of such sessions, to both educate and learn from the community.

Evanston decided to focus its efforts on housing inequities, initially providing a $25,000 grant to qualified people for a down payment on a home, renovations or mortgage help. In March, the city expanded the options to include a direct cash payment.

Black people who lived in the city between 1919 and 1969, or their direct descendants, are eligible.

In mid-August, the city reported disbursing $1,092,924 through the Local Reparations Restorative Housing Program. Another $439,397 is pending. The payments are funded in part through taxes on legalized cannabis sales.

Reparations in KC

Generational Trauma

The reparations framework is similar to reconciliation processes and restorative justice. Reparations are not ongoing city efforts to address inequities.

An apology often can be part of the process.

But the remedies can’t be controlled or decided upon by the entity that did the harm — in this case, the city. Avenues of redress should be decided by the people harmed (or their descendants) and also controlled by them.

Hence, the need for the mayor’s commission and the listening session for community members.

Kamm Howard was the commission’s guest speaker at its most recent meeting. Howard is the former national co-chair of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, also known as N’COBRA.

He authored the book, “Laying the Foundation for Local Reparations.” He now directs a new effort, Reparations United.

“Our aim is to build a lean structure that can select any specific injury issue and educate, organize and mobilize existing local coalitions to develop, initiate, and get funded reparatory programs in multiple communities simultaneously,” according to the organization’s mission.

The group also advocates for cities to adopt slavery disclosures, which require contractors who work with a municipality to admit if it took part in, invested or otherwise profited from the slave trade.

For years, Howard said, he was a “committee of one” working on H.R. 40, the legislation to create a commission at the federal level to study reparations.

“In order for us to win on a federal level, there has to be a sense of some type of unity,” he said of local and state-by-state efforts.

After a nearly 40-year congressional stalemate on the measure, Howard and others are now advocating for President Joe Biden to establish such a commission through executive order.

“The process of repairing, healing, and restoring a people who were injured, due to their group identity, in violation of their fundamental human rights by a government, corporation, institution, or individual.”

N’COBRA’s Definition for Reparations

During the Kansas City coalition meeting in August, Howard led a discussion on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, which is how trauma can be passed down, affecting people physiologically.

Studies of Holocaust survivors and their descendants, Howard said, have begun to document such harms.

“We’re saying that historical trauma that we experienced in enslavement, which ended officially in 1865, could be passed down up to five generations,” he said.

But what also must be considered is that for Black people, the end of slavery didn’t end the trauma. There was sharecropping, the terrorization of the Ku Klux Klan, segregation and other stressors.

“We do know, from the science, that this negative impact to our genes leads to higher rates of cancer, higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, all of the illnesses that Black live with in this country,” Howard said.

He also led the group in a discussion about the damage to Black families, particularly Black men, through over-incarceration during the war on drugs.

“There’s a tremendous amount of energy in the movement right now,” Howard said. “There’s over 100 cities that are engaged in some form or the process of establishing a commission or a task force or looking into it.”

But some efforts stall. And reaching remedies is a lengthy process, he emphasized.

“Evanston is still the only city that has actually delivered any redress in the form of monetary resources,” Howard said.

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS/Flatland.

More on Flatland