July 18, 2023

July 18, 2023

Fees and fines in the justice system can be anything but just.

Too many state and local governments tap legal-system collections, rather than adequate tax systems, to fund shared essentials like public safety and education. As a result, people with few financial resources are loaded with court-imposed debt often levied with little concern for their ability to pay. The cost is borne disproportionately by low-income, Black, and brown families, heightening barriers to economic inclusion and holding back well-being and health.

A growing number of states and localities are choosing a better approach. Catalyzed by advocacy from impacted communities, dozens of jurisdictions from all regions of the country have acted in recent years to eliminate or reform inequitable fees and fines. Momentum for change has continued to build in 2023, with no fewer than seven states enacting substantial improvements.

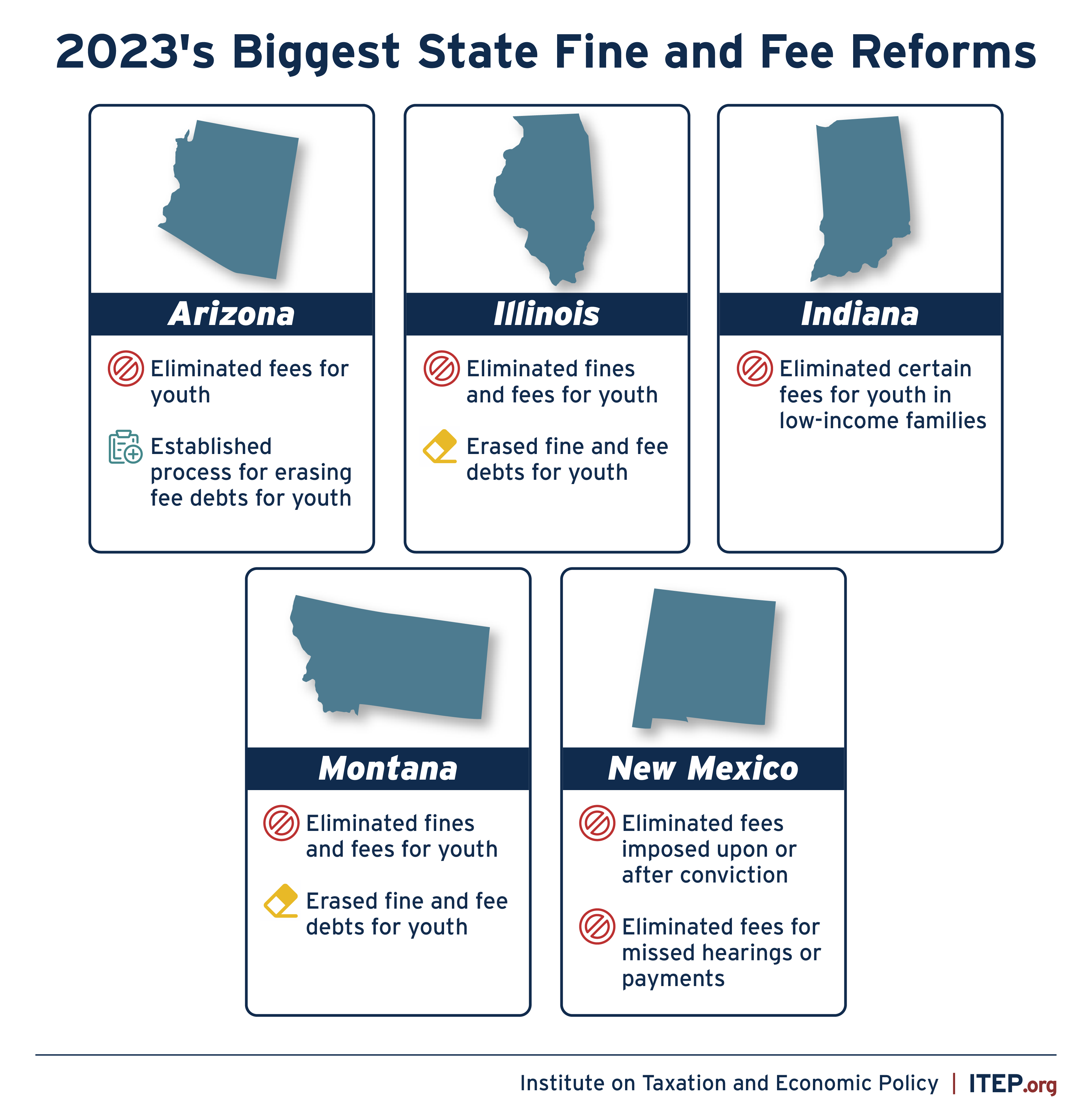

Recent reforms include:

- New Mexico eliminated criminal legal fees statewide this year

- States including Arizona, Montana, and Illinois eliminated youth court fees this year, and Indiana acted to limit fees for low-income families

- States and localities are making important progress in reducing court fees for youth and making fees and fines less overwhelming to low-income households

- Momentum for fee and fine reforms has grown in recent years, with action in over a dozen states and several localities

Moving away from high-pain, low-gain fees and fines puts communities in a better position to thrive. While considerable work remains to be done, these recent actions show the path forward for states and localities—and help illustrate why inequitable court penalties are a dismal alternative to a sound tax code.

Justice fees and fines are financial obligations imposed on people interacting with the criminal or civil legal system. State and local lawmakers establish these sanctions and judges levy them with two aims: to penalize and deter lawbreaking, and to bring in revenue for state and local services. Fees and fines can be levied on both adults and children.

Fines are imposed as penalty for an offense, typically varying in cost according to its perceived severity. Fees, in contrast, can be imposed at all stages of the justice process before, upon, and after conviction—and whether one is found guilty or not. These fees pay for administration of the justice system and other public-sector responsibilities, reducing the role of tax revenue in providing such services.

In addition to any fines incurred, a person could be forced to pay fees for using a public defender, fees for electronic tracking and monitoring devices, fees covering court administrative duties like processing documents and serving warrants, fees for so-called “room and board” while serving time in jail and prison, and fees for using health care or education services behind bars.

Courts also impose universal fees unrelated to the nature of one’s case. For instance, a traffic ticket will commonly include a fine plus several fees often totaling more than the original penalty itself. The fees typically fund assorted government aims such as emergency responder training, K-12 education, correctional facilities construction, and libraries.

It’s common practice for policymakers and courts to layer on fees and fines with little or no consideration of a person’s financial means, piling on costs that can add up to hundreds or even thousands of dollars, quickly becoming unpayable for people with low incomes. These rigid penalties create enormously disproportionate consequences, trapping millions of families in economic hardship and legal precarity, forcing them to sacrifice essentials like health care, food, and housing. The wealthier, meanwhile, are far less likely to face such disruptions. The result, as sociologist Alexes Harris describes it, is a two-tier justice system: one for people with financial means and one for people without.

Black, Hispanic, and Native American households are left at particular disadvantage. Reliance on fees and fines pressures law enforcement and courts to act as revenue collectors, compounding racial inequalities in the justice system and the economy. Considerable evidence shows this worsens biases in policing and leaves communities of color shouldering disproportionate costs.

It hasn’t always been this way. State and local governments greatly expanded their use of fees and fines during the latter part of the 20th century and the start of the 21st century in response to growing revenue needs, inadequate tax codes ill-equipped for an era of soaring inequality, and a federal government losing interest in supporting state and local budgets. Localities faced added pressure from state-imposed restrictions constraining their taxing powers. Onerous fees and fines in the justice system helped take the place of adequate and equitable tax policy, pushing the price of providing public safety, court administration, and other bedrock public goods away from the public at large and onto those ensnared in the legal system.

It’s a status quo that deepens racial and economic disparities in wealth and health, criminalizes financial hardship, undermines families’ ability to invest in their own futures, and damages public safety rather than promoting it.

A growing number of states and localities are demonstrating a better way forward. More than 15 states cut back their use of fines and fees over the last two years, adopting new approaches to eliminate harmful monetary sanctions for children and adults and bring penalties into better alignment with people’s financial realities. Many cities and counties have done the same. These moves come as state and local leaders, spurred on by advocacy from impacted communities, begin to reckon with the true cost of the deeply inequitable status quo.

In one significant move, New Mexico this year ended all fees imposed upon or after conviction in criminal court and abolished fees for missing a payment or hearing, levies that had weighed heavily on New Mexico families struggling to make ends meet. New Mexico’s new law makes it the second state to fully eliminate criminal court fees, following groundbreaking action by California in 2020.

Several states are reforming fees and fines in their juvenile justice systems. Arizona, Montana, and Illinois advanced reforms this year to phase out court fees on kids, and a new Indiana law prohibits youth fees unless a court proves a family has sufficient income and assets to pay. Colorado, Delaware, Louisiana, Texas, New Jersey, and New Mexico are among the states taking similar steps in recent years.

More states and localities are also reining in justice fees that have an especially heavy impact on low-income people and communities. In New Jersey, for instance, defendants will no longer pay fees for using a public defender thanks to a new law. And in Nevada, lawmakers this year decided people in prison will no longer be charged for medical care or forced to pay room and board fees for their own incarceration.

Cities and counties are achieving progress, too. Local governments recently eliminating or curbing fees and fines include San Francisco, Los Angeles County, and Alameda County, California; Dallas County, Texas; Nashville, Tennessee; and Ramsey County, Minnesota. Dozens more are examining and enacting reforms in partnership with organizations such as Cities and Counties for Fine and Fee Justice and the National League of Cities.

State and local policymakers and court leaders are also advancing strategies to make fees and fines more proportionate to financial means. In one sign of progress, a quarter of states now require courts to determine a person’s ability to pay any time penalties are imposed, providing criteria for people with low incomes and other significant financial barriers to receive reduced or waived fees and fines. Jurisdictions have also expanded access to more affordable long-term payment plans.

In addition to requiring or recommending that courts assess ability to pay, some places are doing more to ensure these determinations happen consistently and fairly. One promising innovation in this area is simple-to-use online tools providing straightforward guidelines to judges and people facing fees and fines.

In Washington state, for example, a legal financial obligation calculator launched in 2018 is used by courts to evaluate a person’s financial situation and options for reduced payments or other alternatives. Similarly, California developed a website called MyCitations, introduced as a pilot in 2019, allowing low-income people facing traffic fines to apply for reduced payments. The online tools in Washington and California are accessible to both judges and the public, enhancing equity, transparency, and consistency in the use of fees and fines.

The federal government is stepping up too. Earlier this year, the Department of Justice issued a public notice to state and local courts warning them of the harms from predatory and discriminatory fee and fine practices. The department also recommitted to partnering with states and localities to help improve their policies, renewing an impactful initiative from the Obama administration.

States and localities are increasingly taking steps to curb their reliance on regressive court-imposed fees and fines. They are building a promising track record of results that can inform the path ahead for stronger and fairer communities.

One important insight is that fees and fines are a far less effective revenue source than is often believed. When policymakers load up on unaffordable fines and fees to fund public services, they are redoubling reliance on a costly, counterproductive, and inequitable system—a system that is no substitute for a sound tax code.

State and local governments collect around $14 billion in fees and fines each year. But evidence suggests a large share of these dollars are not made available to support the public services for which they are intended. Instead, much of it simply funds the substantial costs required to collect and enforce fees and fines in the first place. An investigation by the Brennan Center, for example, finds many governments spend nearly as much on enforcement as they collect, and some spend even more than they bring in.

The price of collecting fees and fines is far beyond what it costs to administer a tax code. And that’s before accounting for the substantial human toll of lost employment, disrupted families, and worsened health outcomes.

Even so, evidence from several jurisdictions suggests governments still fail to collect the majority of fees and fines assessed by courts. The result is tens of billions of dollars of debt hanging over people who are unable to pay. The unpaid obligations often collect escalating late penalties which families still cannot afford to pay, deepening their financial hardship. In some states and localities, justice-system debt also puts people at risk of jail time and other costly consequences.

Policymakers can foster better outcomes by reducing unaffordable fees and fines and shifting to higher-quality revenue sources instead. California’s ability-to-pay system for traffic penalties, MyCitations, is one example of a better approach in action, as a recent report shows. When fines for low-income MyCitations users are more affordable relative to income, the report finds, the likelihood of payment grows substantially. Importantly, the total dollars collected are greater when people with lower incomes are asked to pay smaller amounts. In other words, imposing increasingly onerous fines and fees results in less revenue, not more.

The bottom line is that fees and fines impose immense costs and have clear limits as a revenue source. Policymakers’ escalating use of these penalties over the last several decades was neither equitable nor sustainable, and low-income and Black families shouldered a disproportionate share of the overload.

Impacted communities are helping force a long-overdue reassessment, driving momentum for policy changes that can help secure a more just future. Recent reforms enacted around the country will help cut back counterproductive fees and fines, putting communities on stronger footing to thrive.

Ultimately, success at rebalancing fees and fines will likely depend also on state and local leaders recommitting to building a tax system that delivers ample resources for fulfilling public priorities like providing a justice system without relying on onerous poverty penalties. Here there is some cause for concern. This year, a third of states took a move in the wrong direction by enacting costly tax cuts aimed at their wealthiest, including some changes that will further constrain localities’ ability to create sustainable and equitable tax codes. These backward steps are likely to reinforce the revenue pressures that drive states and localities to abuse fees and fines.

But there’s also ample reason for hope. Demand for a better way forward remains strong, and recent progress on fees and fines helps to lay bare the stark cost of inaction.