In the years leading up to the Civil War, some of the biggest enslavers in the United States were not Southern plantation owners, as one might expect, but Wall Street bankers. Northern capitalists like James Brown and his brothers provided lines of credit to clients in the South, who offered their plantations – and the enslaved men, women, and children forced to work on them – as collateral. After the Panic of 1837, bankers like the Browns assumed legal possession of these “assets” when planters defaulted on their loans.

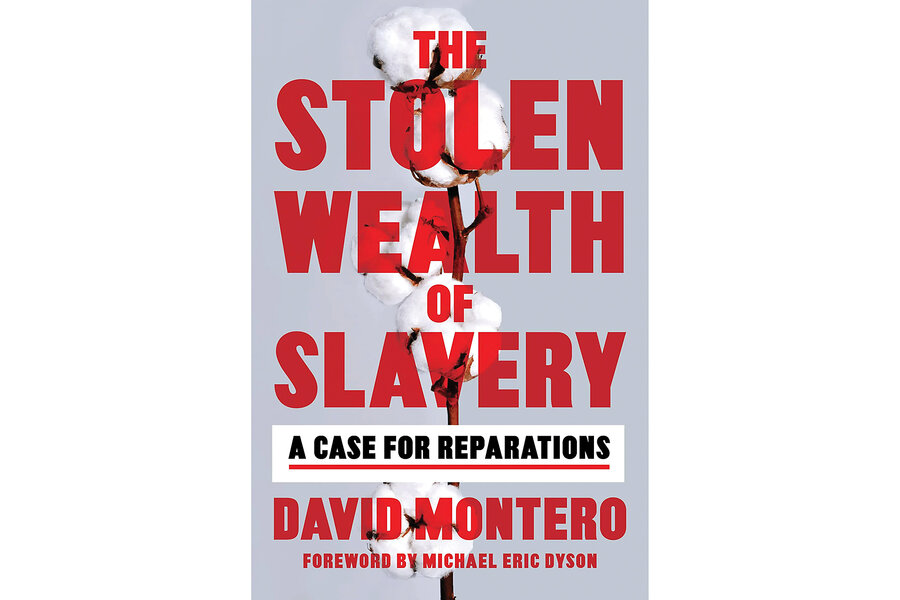

Investigative journalist David Montero untangles the economic ties binding the Browns and other Northern business owners to the slaveholders of the South in “The Stolen Wealth of Slavery: A Case for Reparations.” In his searing and meticulous account, the author argues that slavery has been wrongly perceived as a primarily Southern story. While slavery was centered in the South, Montero observes that much of the wealth it created flowed north.

Those who benefited most from the system of bondage were the men who owned the brokering firms, ships, insurance companies, and banks that turned commodities like cotton, rice, tobacco, and sugar into profits. These enterprises, Montero writes, were “at great physical distance from enslaved people themselves yet directly profiting from that enslavement.”

The author isn’t merely interested in establishing the North’s complicity. Rather, he demonstrates that, in what he calls “the largest money-laundering operation in American history,” Northern business leaders used wealth with roots in slavery to finance legitimate industries. That wealth, he writes, became “the foundations of America’s industrial revolution, a sweeping phase of modernization deeply connected to, though seemingly untouched by, slavery’s chain.” Montero counters the myth that the fortunes created from stolen labor were destroyed during the Civil War.

Because some of the corporate entities seeded with profits from slavery still exist, the book makes a compelling argument for providing some form of restitution to Black communities. The Browns, for instance, who ended up in possession of hundreds of enslaved people, founded corporations that live on as the multibillion-dollar investment banks Alex. Brown and Brown Brothers Harriman.

The book’s final chapters cover the movement for reparations. Montero profiles activists like attorney Deadria Farmer-

Paellmann, who has brought suit against companies with proven links to slavery. Farmer-Paellmann, Montero writes, has “tied corporations to the enormous wealth gap that afflicts African Americans today, arguing that the stolen Black labor that made corporations rich was wealth deprived to Black people and their descendants for generations.”

To date, JPMorgan Chase & Co. is the only American company that has offered any type of restitution for profiting from slavery: In the mid-19th century, the bank held 13,000 Black people as collateral for loans. In 2005, it pledged $5 million in scholarship money for Black students.

Some of Montero’s claims seem overstated, for instance, calling the 19th-century corporate directors of Wall Street “the most active white nationalists of their era, or of any era, in the history of the United States.” Still, at a time when most Americans oppose reparations, “The Stolen Wealth of Slavery” has undeniable force. It has the potential to change minds both about the historical damage that’s been done and about the role corporations can play in repairing it.