Georgia officials released body-worn camera and dash camera footage Wednesday afternoon of the traffic stop and deadly shooting of Leonard Cure, who was exonerated after a wrongful conviction in Broward County in 2020 after spending over 16 years in prison.

The Camden County Sheriff’s Office deputy who pulled Cure over on Interstate 95 about 7:30 a.m. Monday immediately shouted at Cure when he exited his patrol car, ordering Cure out of his truck, the footage shows.

When Cure got out and the deputy told him to put his hands on the back of the truck, Cure said, “I ain’t doing s—.” While Cure was still standing on the side of the interstate near his truck’s door, the deputy pointed his Taser at him, the body-worn camera video showed.

“Step to the rear of the vehicle!” the deputy shouted.

“In the name of who?” Cure said.

“In the name of the law of the state of Georgia!” the deputy said. “Step back here now or you’re getting Tased!”

Cure, who was Black, then put his hands above his head and walked toward the back of his truck. The deputy, who is white, kept his Taser pointed at Cure.

About a minute into the stop, the deputy asked for a back-up unit over radio, signaling that Cure was being “non-compliant.” The deputy moved behind Cure’s back while Cure’s hands were on the back of the truck, the Taser still pointed at him.

Cure asked if there was an arrest warrant when the deputy ordered him to put his hands behind his back. The deputy appeared to then press the Taser and his hand into Cure’s back in order to keep Cure facing forward.

While the officer stood behind Cure, threatening to stun him if he didn’t put his hands behind his back, Cure shouted, “Why am I getting Tased?”

The deputy said he was being arrested for speeding and reckless driving for passing him at over 100 miles per hour.

“OK, so that’s a speeding ticket, right?” Cure said.

The deputy said traffic offenses are criminal in Georgia. As Cure and the deputy shouted at each other, Cure said, “I’m not going to jail!”

“Hands behind your back! Yes, you’re going to jail!” the deputy said, still pointing the Taser. The deputy then fired the stun gun at Cure, still shouting for him to put his hands behind his back.

Once he was stunned, Cure appeared to quickly turn around and began swinging his arms at the deputy, who continued stunning him.

Both Cure and the deputy wrapped their arms around each other’s heads, knocking the deputy’s glasses off his face. Cure appeared to push the deputy into the back of his truck and pushed the deputy off him by grabbing his face, the video showed.

Cure then grabbed the deputy’s face and pushed his head backward while the deputy hit him with a baton. Cure appeared to be grabbing the deputy’s head from underneath his chin and pushing him backward while saying, “Yeah, b—-,” when the deputy shot him. The fight lasted about 30 seconds before the shot was fired.

Cure hit the ground, and the deputy said “shots fired!” over the radio and called for more officers. Cure could be heard saying, “too late,” while on the ground as the deputy called for help.

Cure tried to get up multiple times after he was shot, video showed. His arms appeared to be flailing while he was on the ground.

The deputy continued pointing his gun at Cure and ordering him to stay on the ground. An armed Brinks security guard pulled over on the highway’s shoulder and pointed his gun at Cure, backing up the deputy, while they waited for more officers to arrive.

The deputy handcuffed Cure, who was then lying motionless on the road’s shoulder, while the Brinks security employee kept his gun pointed at him. Blood could be seen soaked through Cure’s light-colored tank top and smeared on his arm as the deputy handcuffed him.

“Hey, you look at me,” the deputy said to Cure, who was unresponsive. “You ain’t goin’ no damn where.”

The deputy opened an automated external defibrillator box to start life-saving attempts, the video showed, before another deputy took over.

At least a dozen paramedics and officers arrived on the highway shoulder within minutes.

Several first responders gave Cure chest compressions for minutes before they loaded him into an ambulance.

The deputy who shot Cure sobbed behind his patrol car while others tried to comfort him.

“I’d rather it be you sitting here,” someone told the deputy while he cried. “You’re good.”

‘Lived in fear’

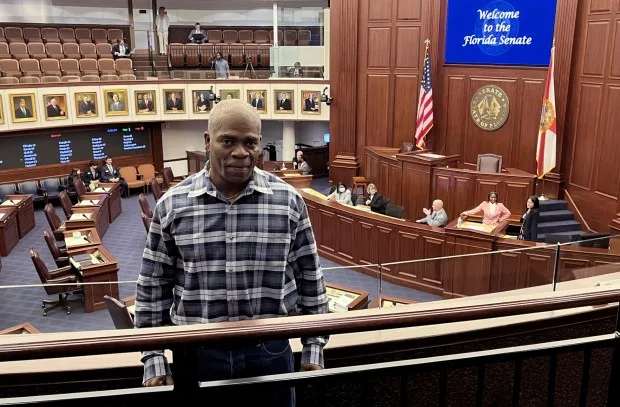

After serving 16 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, Cure was embarking on a new chapter in his life, said Seth Miller, executive director of the Innocence Project of Florida.

He had just closed on a new home. He had new bank accounts and investments, courtesy of an $817,000 compensation payment from the state of Florida. All those assets are in limbo now, Miller said, until Cure’s mother and family figure out what happens next.

“When he left his mother’s house, he told her ‘I love you and I’ll be back to see you,’” Miller said.

He was on his way home from visiting his mother in Port St. Lucie.

It was Cure’s worst fear, like so many exonerees, that one day he would be sent back to prison.

And it was his mother’s worst fear too, any time he stepped out the door, that the justice system would take her son away again, so much so that she told him to have a way to record video in his car in case he was ever stopped by police.

So much so that, when officers arrived at her door on Monday, she told them first, “police killed him.”

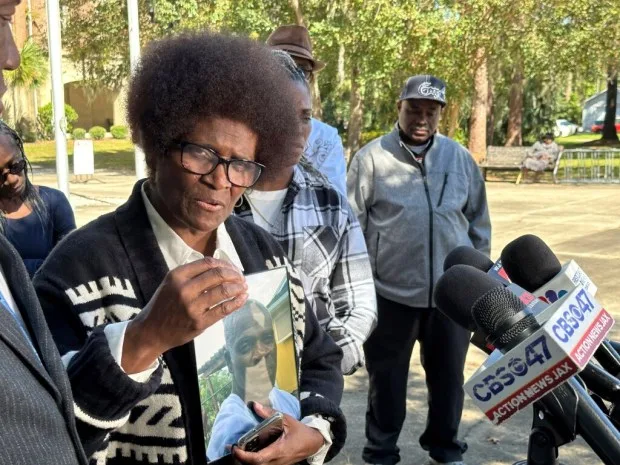

“Before they could tell me,” Mary Cure told reporters at a news conference outside the Camden County Courthouse in Georgia on Wednesday afternoon before the videos were released. “Because I lived in fear and so did he.”

Her son, a former Broward resident, was freed in 2020 after the Broward State Attorney’s Office reviewed his case and vacated his charges, the first man exonerated under its new Conviction Review Unit.

“It is God-awful that he would escape that injustice to have his life claimed by more bias,” civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who is representing the family, said Wednesday. “We absolutely do not believe, if he was a white citizen, he would’ve been killed for a traffic stop.”

In a statement after watching the video, Crump said it was “tragic that there wasn’t an attempt to de-escalate the matter from the beginning.”

“When you have escalation met with escalation, nothing good comes out of it,” Crump said. “When an officer said, ‘I’m going to arrest you and take you to jail,’ he was triggered psychologically.”

After watching the video, Cure’s brother Michael Cure also said the deputy did not de-escalate the interaction.

“The officer got out of the car extremely aggressive, yelling and screaming commands, and my brother complied,” he said. “He did comply, so after watching the video, I do believe things could have been handled differently, but I also believe the officer got out being extremely aggressive.”

Cure was “extremely intelligent,” charismatic, and forgiving, his brother said.

“He forgave the idiots that locked him up,” he added. “That’s how forgiving he was.”

The day in 2003 when Cure was arrested for the robbery, he was living with his brother, working two jobs, Michael Cure said. He would wake up at 5 a.m. to take the bus.

That day, he was at an ATM miles from the armed robbery at a Walgreens near Dania Elementary School only a half-hour before it occurred, and at his construction job less than a half-hour later. A receipt from that ATM became crucial evidence of his innocence.

But a jury at the time found him guilty anyway. He was sentenced to life in 2004 as a habitual felony offender because of his criminal record.

Florida Department of Corrections inmate records show Cure had prior prison history in 1989 stemming from charges of grand theft of a motor vehicle, battery on a law enforcement officer or first responder and escape in Miami-Dade County as well as a cocaine-related charge in Hamilton County.

Over the course of Cure’s years locked away for an armed robbery he did not commit, his mother and siblings drove across Florida from prison to prison, visiting him.

Throughout that time, he struggled, his mother said. At one point, he was stabbed in the back close to his kidney. She would go without hearing from him, wondering if he was dead or alive. Sometimes she would drive all the way to the prison, only to be told she couldn’t visit him that day.

He was offered plea deals and rejected them all, maintaining his innocence.

Finally, in 2020, the Broward State Attorney’s Office brought his case before a judge. He was free.

But the system continues to fail exonerees after they are released, experts and advocates say. For the few years after his release, Cure struggled with severe PTSD, according to Crump, as many exonerees do.

For those whose convictions are overturned, exoneration is often not a happy ending. Many struggle with severe PTSD following their wrongful conviction, which psychologists have often compared to the trauma experienced by war veterans.

Many report significant personality changes, including becoming paranoid and anxious after their convictions; others report feelings of threat and fear when in public.

They fear the possibility that they could be sent back at any time, said Justin Brooks, a criminal law professor at the University of San Diego and one of the co-founders of the California Innocence Project, who has worked to help free more than 40 people who were wrongfully convicted.

“Prison in general makes people dysfunctional,” Brooks said. “When you add a layer of, you’re innocent in prison, that turns into paranoia and anger.”

Police officer misconduct, including outright lies and the planting of evidence, have led to some wrongful convictions, though more often than not, negligence is the main reason, Brooks said.

Returning to their lives, exonerees struggle to adjust. Often the government doesn’t do much to help them as they navigate heaps of paperwork and try to find mental health care. In some states, they receive no compensation. In Florida, Cure received $817,000, the equivalent of about $50,000 a year.

That’s “peanuts,” his family members said Wednesday.

Brooks has never heard of something like what happened to Cure, but says many of his clients fear — and face — encounters with police after their exonerations.

“Sadly I wasn’t surprised by it,” he said of the shooting. “I wasn’t surprised because I could easily see the combination of the person who’s been wrongfully convicted reacting in a really strong way to police wanting to take him into custody. And I wasn’t surprised police might overreact and have a deadly response to that. It’s a combination of both those things that just unfortunately doesn’t surprise me.”

Cure would rarely talk about his time in prison, his mother said. But one morning, she said, she was making him breakfast when he broke down and cried.

“They took my life,” she recalled him saying. “They took it.”

Studies show Black Americans face a disproportionate risk of being wrongfully convicted of crimes or killed by police.

Black people make up 13.6% of the American population but 53% of the 3,200 exonerations listed in the National Registry of Exonerations, according to a 2022 report by the registry. Black Americans are seven times more likely than white Americans to be falsely convicted of serious crimes, the report said.

‘There is a problem here in Camden County’

“I love you and I’ll see you soon,” Cure told his mother as he left her home on Monday. But she felt uneasy, she said, the same unease she always felt when he left her, that he might get stopped, taken back to jail, or worse.

“This was her worst fear,” Crump said of Cure’s mother. “Now that he proved they lied on him before, that police were going to do him in. This was her worst fear.”

Some say she had good reason to feel that way. Cure’s death is part of a pattern of injustices in Camden County, advocates say, including during traffic stops and in the county jail.

“Let’s be clear,” Timothy Bessent, president of the NAACP in Camden County, said at the news conference Wednesday. “There is a problem here in Camden County with law enforcement. This is not the first incident. And we do understand it won’t be the last.”

The insurance carrier for the Sheriff’s Office dropped the county because of the amount of lawsuits filed against them, according to The Current. The majority of claims arose out of incidents at the jail.

And in January of this year, a deputy was criminally charged after pulling a woman over for running a stop sign, then ramming her head into a car, The Current reported. That deputy was fired.

Black people in Camden County don’t trust the police, Bessent said. He wants the Department of Justice to get involved.

The officer who shot Cure has been placed on administrative leave during the investigation. Neither the Sheriff’s Office nor the Georgia Bureau of Investigations have released his identity, but he identifies himself as Staff Sgt. Aldridge in the video.

Capt. James Bruce, the spokesperson for the Camden County Sheriff’s Office, told the South Florida Sun Sentinel earlier on Wednesday that it would “probably be a little while” before the incident report for the shooting was complete.