From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Black maternal mortality, once a nearly unspoken and taboo topic discussed by families in private, has emerged as a topic addressed by everyone from the World Health Organization (WHO) to the White House to Pennsylvania state leaders.

Maternal mortality refers to deaths due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth. The WHO reports maternal mortality has increased worldwide, and according to its April 2024 publication, on average, almost 800 women died each day in 2020 from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth — with nearly 95% of them occurring in low- and lower-middle-income countries and most having been preventable.

Shockingly, America is not exempt. In fact, according to “The White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis,” women here are dying from pregnancy-related causes at a higher rate than in any other developed nation.

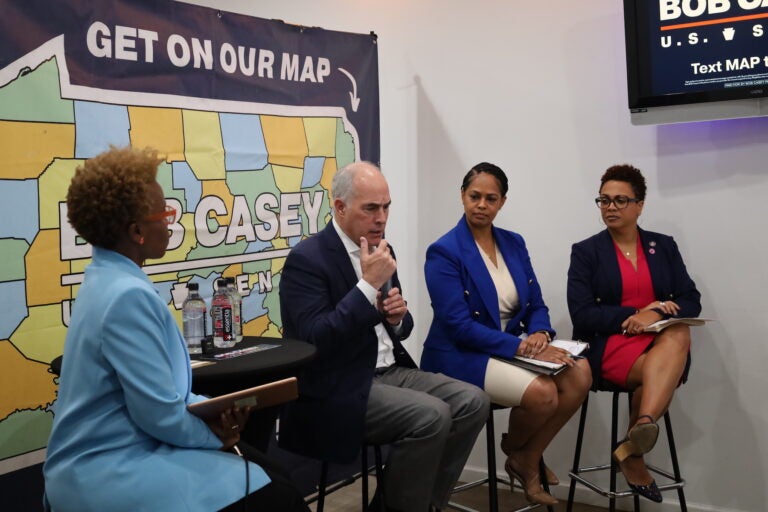

U.S. Sen. Bob Casey joined Montgomery County Coroner Janine Darby, M.D., and Pa. Reps. Morgan Cephas and Gina Curry for a conversation on Black maternal health at a campaign stop last week at Mingle Event Studio, in Philadelphia.

Cephas said for Black women in Pennsylvania, the joy of childbirth has become a sobering experience, accompanied by the fear that giving birth could lead to death. “In Pennsylvania, it is mirrored after what’s happening across this country,” Cephas said. “Black women are three times more likely to die due to childbirth than our white counterparts; 51% of the deaths are occurring during the postpartum period, and 92% of the deaths actually are preventable.”

Cephas and Curry are co-chairs of the Pennsylvania Black Maternal Health Caucus, which aims to rectify the issues that surround Black women’s mortality rates. But they can’t do it alone, Casey told the crowd of mostly Black women, saying men have a role to play too.

“Well, part of it is, just to recognize the problem, and men have to get in the game on this and help us with this, pass legislation (and) change policy,” said Casey, who added that discrimination contributes to the racial disparities. “Often the care that Black women are getting in our healthcare institutions is discriminatory. They’re being treated unfairly in healthcare settings. We’ve got to train people and hold healthcare institutions accountable for that kind of discrimination,” said Casey.

Cephas agreed, saying, “That needs to be called out. It needs to be addressed and it needs to, you know, be talked about, which is one of the reasons why we introduced a bill requiring implicit bias training and cultural competency training for all medical professionals. We all come to the table with some sense of bias. We have to again be able to recognize that and ensure we’re providing competent care, but the only way that we get a chance to do that is by addressing that issue directly.”

Both agree the outcomes are largely due to systemic inequities, including maternity care “deserts” where resources are lacking or don’t exist. ”If you can’t access care, I don’t care what your socioeconomic status is,” Casey said. “You’re not going to have a good result in the pregnancy.”

Complicating the picture, statistics show that insured, college-educated, wealthy Black women are also dying in numbers higher than their white counterparts.

“Black women are seen as strong women; we can deal with the pain, right? And so we’re not checked or sometimes we’re too animated. And then they don’t listen to our woes or our symptoms as well. So it’s a lot of historical things,” said Darby, adding that as the Montgomery County coroner, she sometimes sees the most tragic outcomes.

“As a medical doctor, this is so important to me, not only being a Black mom who has her own story and is also seeing patients with their stories as well,” she said. “But as a health advocate, as a medical professional, I think it’s important to get the awareness out, making sure that Black mothers are taken care of, that they have the access, awareness, education, resources, and the support.”

Darby advises Black women to have an advocate before, during, and after childbirth. “Make sure you have someone that’s advocating for you, whether it’s your partner, if you enlist a midwife or doula care as well. But don’t do it alone,” she said.

Unfortunately, most insurance policies do not cover midwives or doulas, which provide emotional care and support through childbirth and beyond. Some statistics show their services can save lives, and their work has become a safety net for pregnant Black women.

Casey said it’s important for Congress to make third-party advocates affordable to women who need them most. “It is about changing Medicaid law or expanding Medicaid… to allow Doula services to be reimbursed, to be covered under Medicaid, and midwives to the role they play to be covered by Medicaid,” he said.

Casey said that much of what they spoke about was covered in the so-called Momnibus Act legislation, which he credited Vice President Kamala Harris with starting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.