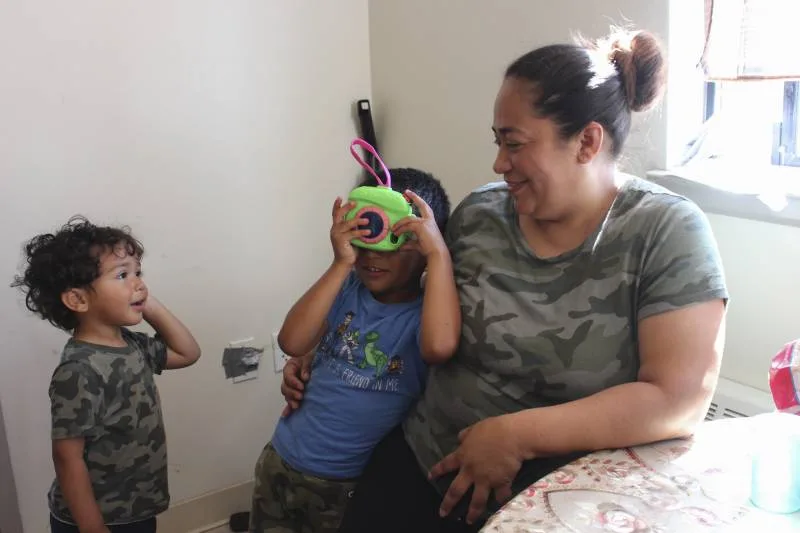

Mirna Arana, a Guatemalan immigrant who now lives in San Leandro, in Alameda County, with her two young children, said she hasn’t received any of the $183,000 the California Labor Commissioner’s Office awarded her, including for unpaid regular wages and overtime. She often worked 12-hour shifts cleaning homes and office buildings, she said, but her former employer, Rene Herrera at Maid No. 1 Services, only paid her about $5 an hour.

Her case was referred about two years ago to a small unit at the state agency that focuses on helping workers collect unpaid wages. But, by then, her employer had already filed for bankruptcy, she said. Efforts to enforce the judgment in her favor through bank levies were also unsuccessful.

“It has been such a stressful, difficult time,” said Arana in Spanish.

The experience of feeling exploited at her job inspired the 36-year old to start her own house cleaning business, and she vowed to treat any employees she might hire fairly. But while she enlists a number of clients, Arana must still rely on government subsidized food assistance to get by, and she worries frequently about how to pay for her apartment’s rent.

Five years after she first filed her wage claim, she said the judgment she won is “just a piece of paper.”

“It feels like I didn’t achieve anything. That all my effort with this claim, to try to make sure that other workers didn’t go through what I did, wasn’t worth it,” Arana said.

California Secretary of State records show Maid No. 1 Services was terminated in May 2018. Herrera did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Santa Clara County’s solution

In Santa Clara County, the Food Permit Enforcement Program has helped collect more than $110,000 for workers since 2019, according to county officials. The program, which began as a pilot in a few cities, was halted during the pandemic before it was relaunched countywide last summer.

KQED contacted three workers who recovered lost wages through the program, but they declined to comment, as they did not want to be publicly associated with a wage dispute.

The county’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement regularly combs state records to identify food permit holders with unpaid judgments. If a business owner does not respond to a series of letters within 45 days, their permit could be revoked, though nobody has lost one yet, said Jessie Yu, who directs the office.

“The county focuses on food permits because we see a nexus between vulnerable worker populations and a large number of labor violations in the food retail industry,” said Yu. “We want to make sure that our citizens are taken care of and that if they are working for eight hours, they get paid for eight hours.”

The first-of-its kind program works across jurisdictions to help ensure retail food vendors in the county comply not only with local laws, but state and federal ones as well, said Jenn Round, a labor standards enforcement expert at the Workplace Justice Lab at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

“The Santa Clara food permitting program is unique and innovative nationwide,” said Round, who works with local, state and federal agencies across the U.S. to more effectively protect the rights of low-wage workers.

“I haven’t heard of any other county in the country that is doing anything like that… to take on the challenge of enforcing a judgment that’s been issued by a different (state) agency,” she added.

This comes as the Labor Commissioner’s Office struggles with a staffing crisis that dozens of employees at the agency say cripples its mission of ensuring a fair day’s pay in every workplace.

Most of the approximately 30,000 wage claims workers file annually are settled with employers or dismissed. But those that aren’t, end up in court judgments, often after a years-long process due to major delays at the agency.

Even after they win, many workers are then left to their own devices to try to collect on those judgments. A fraction of those orders — involving people who labor in low-wage industries such as agriculture, construction and restaurants — are referred to the Labor Commissioner’s Judgment Enforcement Unit for help.

“These specific employers sometimes that come through our office will do everything they can to avoid these payments,” said James Yang, a senior deputy who works at the unit. “They start moving property, they start trying to sell or transfer the business, getting rid of real estate… It’s not easy.”

Yang says the unit is “very effective” at clawing back money in cases they can focus on, using collections tools that range from liens and bank levies to complex investigations to try to chase and seize assets to collect lost wages.

But because the unit has fewer than two dozen staff positions statewide, and only 13 of those are filled, it lacks the capacity to intensively investigate the thousands of cases it handles.

Even though Santa Clara’s food permit enforcement initiative only targets a small subset of unpaid judgments, it still sends a powerful message to employers, said Yang.

“It’s one county, one specific industry, we are talking about here. But it’s been very helpful,” he said. “And it’s garnered very positive attention.”

Other counties in California have expressed interest in setting up programs like Santa Clara’s to hold more wage thieves accountable, he added.

Several studies point to a high proportion of wage theft victims who are unable to collect on the judgments in their favor. The California Legislative Analyst’s Office found that fewer than half of workers who received an award for unpaid wages recovered them from their employers.

Over the last decade, more than 6,500 unpaid judgments, totaling nearly $85 million, remained open after being referred to the enforcement unit, according to a spokeswoman with the Department of Industrial Relations, which oversees the Labor Commissioner’s Office.

The total amount owed to workers is likely much higher, as those figures do not include cases that were not referred to the unit and whose outcome is not known to the agency. Also omitted are judgments stemming from investigations by the agency’s Bureau of Field Enforcement, which often issues citations totaling millions of dollars for widespread violations impacting dozens of workers at a time.

Wage theft ‘not acceptable’ in Santa Clara County

The numerous unpaid judgments show it’s “absolutely critical” for city and county governments to do more to disincentivize wage theft, said Silver Taube, the attorney working with Santa Clara County’s Wage Theft Coalition, and a supervising attorney at Alexander Community Law Center at Santa Clara University Law School.

“I believe it’s a business model. I think they know there’s no consequences, and they just don’t pay,” said Silver Taube, who has pushed for greater consequences for businesses with labor violations.

The Wage Theft Coalition advocated for Santa Clara County to establish the food permit enforcement program, and they helped convince cities, like Milpitas and San Jose, that it’s to their benefit, too, to deny business permits or contracts to employers with unpaid judgments at the Labor Commissioner’s Office.