The pews are increasingly empty at historically Black churches in San Francisco’s Fillmore neighborhood, once called the “Harlem of the West” because of its bustling Black community.

Places of worship once visited by some of the country’s most influential Black leaders, such as W.E.B. Dubois and Martin Luther King Jr., have lost hundreds of members in recent years. As rising costs of living have kept many former Black residents away from a neighborhood they once helped build, many of the historic religious institutions that grew alongside them are on life support.

The 80-year-old Jones Memorial United Methodist Church on Post Street recently cut one of its Sunday sermons as its membership declined from roughly 200 people to 40, if you’re counting the choir members. Yulanda Williams, a lay minister at the church, said the congregation was forced to cut back programs for the sick and elderly as well as rehabilitation services for people leaving prison.

At the historic 171-year-old Third Baptist Church on McAllister Street, which supports after-school programs for Black youth and food for the hungry, attendance has dropped from over 1,000 people in the 1970s to as low as 200 people now, said the Rev. Amos Brown.

Alongside the disappearance of Black churches, Black businesses have struggled to survive. Arnold Townsend, the pastor at Without Walls Ministries on Steiner Street, said he must drive to the East Bay after church every Sunday to find authentic soul food.

“To see these institutions disappear, you have to understand what it does to the emotional psyche of Black people,” Townsend said. “We have no identifiers in our town anymore.”

The struggles of San Francisco’s Black churches coincide with declining religious participation across the country. Some local religious leaders say it’s time for the institutions to reinvent themselves. Others blame city officials for failing to provide affordable housing for their members as well as protection from property crime and social issues like homelessness that plague San Francisco.

Some longtime members of Black churches in the Fillmore make lengthy commutes from other parts of the Bay Area, but many have found churches near their new homes or stopped attending church altogether. Some members have simply grown too old to attend, and the churches are struggling to attract younger congregants.

For Andrea Patton-Housley, a 30-year member of Jones United Methodist Church, the declining church membership has intensified her obligation to commute from the East Bay to the Fillmore every Sunday. Patton-Housley grew up in San Francisco and attended church here, but she moved to the East Bay in 2006 to buy a home because the city was unaffordable.

“The church is like my family,” Patton-Housely said. “There’s not that many African Americans left in the Bay Area.”

A Difficult Balance

San Francisco’s Black population decreased from 13.4% of the city’s total population in 1970 to 5.7% in 2021. The drug and housing crises have hit Black residents particularly hard, with Black people making up 38% of the city’s homeless population and 32% of overdose deaths, according to the most recent data available.

These disparities, some community leaders say, are symptomatic of the city’s failure to support Black institutions that were largely expected to address the crises.

“The church has been a lifeline to keep people from getting into trouble,” Williams said. “But how long are we expected to try and resolve issues that go far beyond our reach?”

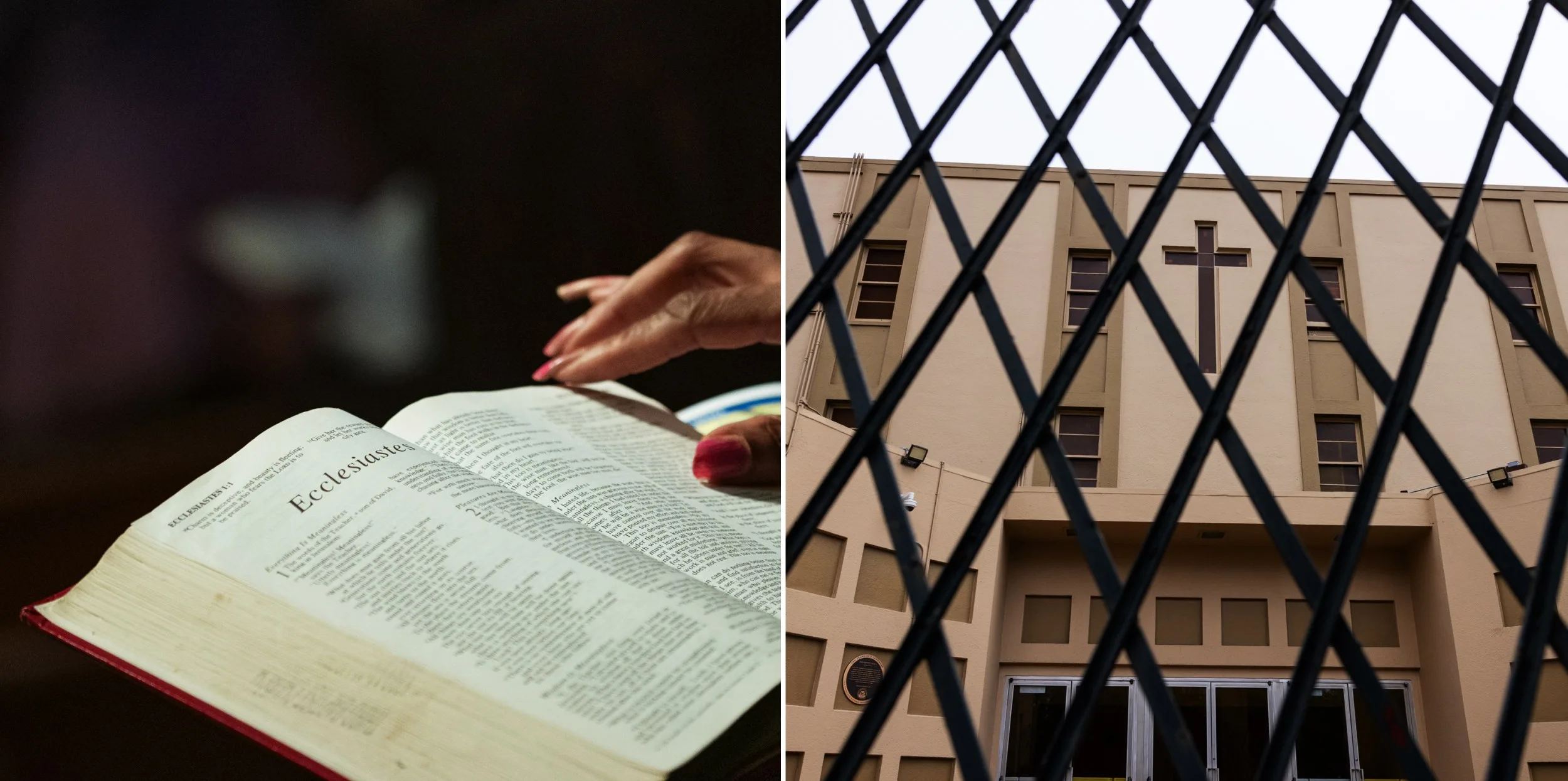

Pastors say they’re faced with balancing spiritual obligations to help those in need and coming to terms with their own vulnerabilities. In response to a rise in break-ins, some churches in the Fillmore have moved away from open-door policies and have installed high-tech security systems.

Brown, pastor of Third Baptist Church, said he’s spent upward of $75,000 to repair damaged property and install fences and cameras, expenses that have added to the financial woes presented by declining membership.

This year, thieves stole catalytic converters from vehicles in the church’s gated lot—one of three break-ins the church endured over the past six months.

Brown, who studied under Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and is the president of San Francisco’s NAACP chapter, said he wants to see the law enforced evenly rather than not at all. He said he thinks the city fosters a climate that’s conducive to crime, placing undue burden on churches and businesses.

“The Black community is under siege,” Brown said. “The leadership of the city needs to step up and stop debating in ideological scum-fights.”

Third Baptist operated a homeless shelter until its plumbing system was clogged by hypodermic needles, a problem that cost $50,000 to repair, Brown said. First Friendship Baptist on Steiner Street also ran a homeless shelter until declining membership made the operation unsustainable, according to Townsend.

Other churches in the area say they’ve struggled with increasing homelessness without having the resources to help. Between 2019 and 2022, the unsheltered homeless population in the Fillmore’s supervisorial district rose by roughly 160 people, though it remained much lower than in other areas of the city, according to a one-night count in February 2022.

Williams said the smell of urine has seeped into her church from homeless encampments on the adjacent sidewalk. Yul Dorn, pastor of Emmanuel Church-God in Christ on Hayes Street, said he’s caught people sneaking onto the church’s roof, using drugs and even sleeping there.

“I’ve never seen churches desecrated to the extent that I’m seeing today,” Williams said.

In the Tenderloin, the epicenter of the city’s homelessness crisis, Glide Church—a hub for social justice in the neighborhood—is no stranger to the issues described by ministries of the Fillmore.

“It gets wild at Glide. I mean, yesterday, someone came in and threatened to kill everybody,” Senior Minister Marvin K. White said on Wednesday. “We acknowledge that it is a thing, but we also know that bringing folks together is part of the solution.”

White said two types of congregants come to his church on Sundays: One group attends for the sermon, while others attend for a free meal. He said he believes bringing those groups together should remain at the core of the church’s mission.

“Those who are privileged need to look at those people in the face who are suffering, and we all need to see each other,” White said.

Decades in the Making

The challenges for the Fillmore’s Black churches started well before the city’s current drug and homelessness crises.

In the 1960s, the Fillmore neighborhood was the focus of a federally authorized “urban renewal” project, which ostensibly aimed to improve struggling urban areas by building new housing and storefronts but forced an exodus from the area.

The Board of Supervisors is weighing recommendations set forth by a reparations committee, which is proposing investments in education and health for Black children and mothers, strategies to employ more Black teachers, psychiatric help for people growing up in underserved neighborhoods as well as cash payments for Black San Franciscans. But next steps for the proposals remain unclear.

Declining church attendance is hardly unique to Black churches or to San Francisco. Across the country, religious participation in churches has fallen over the past decade. The share of people who identify as Christian in the U.S. declined from 78% to 63% between 2007 and 2021, and only a quarter of people say they attend church at least once a week, according to a study by Pew Research.

White, of Glide Church, said he’s begun to move away from the Bible in some of his sermons as a growing number of people separate themselves from religion. White said the church’s evolution will require meeting people where they are in their beliefs and working together with other ministries.

“I’m like Oprah. You get a theology. You get a theology. You get a theology,” he said. “I think part of my job as a minister. … Is to remove these barriers created by these dead white theologians.”

Bobby Sisk, a steward of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, said he considers his church one of the lucky ones, though attendance has decreased by roughly 60% since the 1970s. Sisk said he believes churches need to evolve and learn how to attract more diverse crowds and younger members in order to survive in San Francisco.

“The churches were thriving. These were packed houses to capacity. Now, in some cases, you have some that are on life support,” Sisk said. “The churches themselves have to start to think differently.”

Others say the city needs to provide more support to these institutions before Black people disappear entirely from the fabric of San Francisco.

“In 10 years, it’s quite possible that we could have more Black San Franciscans unhoused than housed,” Townsend said. “But it seems like mostly they want to ignore it and pretend that it’s not happening.”