Editor’s note: This is the 23rd in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

George W. Parker, former resident of Pensacola best known for his spirited defense of Rev. L.B. Croom in the 1905 streetcar segregation case, died on July 9, 1921, in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Cause of death is unknown.

Mr. Parker was born in Alabama in 1864. He very well may have been young George W. Parker living with James and Elizabeth Parker in 1870. George and three-year-old Francis Parker, both identified as a “mulatto,” lived on the Parker farm near the Florida-Alabama border. In 1870, James Parker, White, grew 450 bushels of “Indian Corn” on his 60 acres of farmland. The young Parker boys may have explored the adjoining 380 acres of woodlands when they were not helping care for the livestock that included 25 pigs, 9 sheep and assorted cattle, horses and mules. James had enslaved a 20-year-old Black woman in 1860.

George eventually left the farm and married the widow, Eliza “Lizzie” Abels, in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1889. George and Lizzie then made their way to Pensacola, joining thousands of Alabamians who flocked to the booming port city.

Righting the past:Their history wasn’t just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

George W. Parker first appears in Pensacola in 1895 serving as the recording secretary of the local chapter of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners. Pensacola was a union town at the turn of the century, and Black unions exercised significant political and cultural influence. “In no other city in the union,” wrote an observer in 1905, “has the colored man so thoroughly control of the labor situation in both the common and skilled vocations.”

Parker also joined the city’s thriving Masonic community. By 1900, he was serving as secretary for the Excelsior Lodge, one of the five Black Masonic lodges that were then active in Pensacola. He would later become the secretary of a second Masonic lodge, the Royal Arch Chapter. In 1904, the Excelsior Lodge elected Parker the “Most Excellent Grand High Priest.”

Parker was equally active in Pensacola politics. In the run-up to the 1903 municipal election, he “made a strong and intelligent plea” before fellow Black voters in support of the incumbent mayor, C. Moreno Jones. Parker shared the stage with many local Black leaders, including Rev. L.B. Croom that evening. He would later defend Croom in court, though the two would clash in the political realm during the contentious 1908 election.

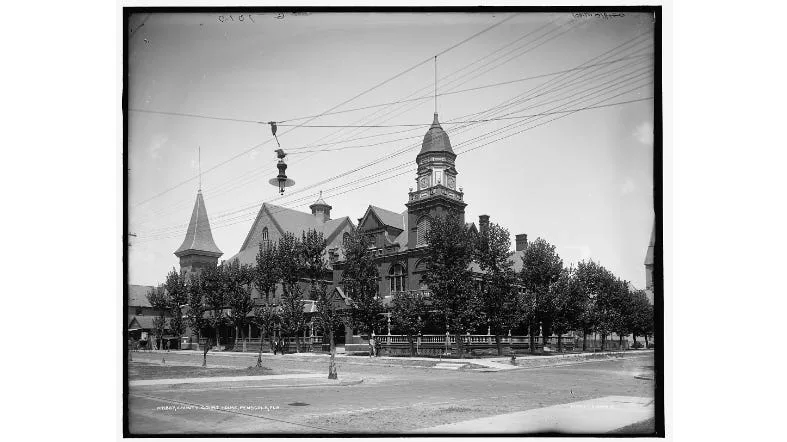

At some point, Parker studied the law and was admitted to the bar. By 1905, he was one of three Black lawyers practicing in Pensacola. Described as a man of “exceptional talent,” Parker practiced in local, state and county courts. His office at 108 S. Tarragona street was a short walk from his residence at 107 E. Chase street, though his office and residence would change in subsequent years.

Parker was a leading member of Penacola’s thriving Black middle class. Before the imposition of increasingly aggressive Jim Crow legislation and the outbreak of a new round of racial violence upended Pensacola, the city was accurately described as an “ideal Negro business community.” Parker served his community alongside four Black physicians, dozens of teachers and a full slate of Black-owned businesses that met the needs of a city of 21,505 residents, half of whom were Black.

Parker’s cases occasionally garnered the attention of the local newspapers. In December 1904, he successfully defended Frank Williams, a “poor negro” suspected of being the notorious murderer, Hayward Carr. The following fall, he defended Rev. L. B. Croom after Croom intentionally violated the city’s new streetcar segregation ordinance. The ordinance had been drafted after a state law segregating streetcars was ruled unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court. Parker argued in court that the new ordinance was also “in violation of section two of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.” Judge Charles H. Laney dismissed Parker’s argument and sentenced Croom to 30 days in the city jail.

[PNJ: ADD link to Croom Obit]

George and Lizzie’s only child, Margaret, was born in 1910. Lizzie may have died during childbirth. George continued practicing law in Pensacola through 1913, though he left the city in 1911, first to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and then to Muskogee, Oklahoma.

By the summer of 1913, he was one of 10 African Americans attorneys practicing in Muskogee. As he had in Pensacola, Parker handled criminal and civil cases, including civil rights, divorce and real estate cases. George occasionally partnered with William H. Twine. Known as the “Black Tiger,” Twine had co-founded Oklahoma’s first African American law firm in 1891. The two worked together on the Legal Advisory Board for the Selective Service Draft Board during World War I.

Parker thrived in Muskogee, earning the moniker the “Old Warhorse of Muskogee.” In 1916, he married Mittie Caesar, “the wealthiest colored woman in the state.” And he once again threw himself into local politics. A member of the Muskogee Democratic Committee, Parker represented Muskogee County as a delegate to the 1920 Colored State Democratic Convention where he was appointed to the party’s executive committee.

Parker once again gained renown after World War I for his representation, alongside Twine, of Kid Kelly in the successful appeal of Kelly’s murder conviction. But Parker would not live to see Kelly’s conviction overturned. He died on July 9, 1921. His estate papers identify his widow, Mittie, a daughter, Margaret, and two sons, Whitlow and Frank.