One of the joys of watching the S.F. Silent Film Festival’s offerings is being introduced to a cinematic rarity supposedly lost to time. Take Joseph De Grasse’s melodrama “Flowing Gold,” an adaptation of Olympic medal winner Rex Beach’s novel of the same name. This film had not been seen since the silent era, and the only existing elements of the movie were found in the Czech National Film Archive. The festival’s digital restoration work on De Grasse’s film included drawing from Beach’s book for the English intertitles.

The festival screening of “Flowing Gold” might be called the public premiere of the restored edition of the film. Whether this tale of oil discovery fever in rural Texas was worth the wait will be discussed below.

When the Briskow family discovers oil on their land, they become instant millionaires. But with their sudden financial windfall comes a raft of problems. Their land and the nearby town of Ranger, Texas becomes a magnet for fortune seekers and scam artists. One of these possible fortune seekers/scam artists is ambitious hustler Charles Gray, who’s not letting having only three cents to his name stop him from finding a way to build a fortune. But will Gray ultimately be on the Briskows’ side or is he just as much of a menace as evil banker Henry Nelson, who had tried to foreclose on the Briskows’ land before they could discover the oil wealth there?

Described like that, the bones of “Flowing Gold”’s plot could with some tweaking work as a story set in the present day. Certainly the bit about Ma Briskow having more money than taste is a phenomenon still seen today in such things as the gold decor overkill of the Orange Skull’s gaudy New York City residence. Gray seems to be a prototype of the present day’s “fake it till you make it” hustlers with his passing himself off in Dallas as a wealthy financier. And “Flowing Gold”’s natural disaster finale would be a kindred spirit to current Hollywood blockbusters’ special effects excess.

On the other hand, any present day remake of “Flowing Gold” would need to leave the original’s casual racism and sexism behind. The only positive aspect of Gray’s scamming a Black waiter out of a tip is its being the only casually racist scene in the film. Still, the impression can’t be shaken that the (white) viewer of the time would have been amused by Gray’s “cleverness.”

Allegheny (“Allie”) Briskow may be the film’s heroine. But her main storyline involves apparently unrequited mooning over Gray’s attention. Pa Briskow questions the wisdom of her attempts at using the family’s wealth to get an education in the social graces. To Allie’s credit, she doesn’t turn into a pile of helplessness during the film’s finale. Yet this viewer does end up wishing Allie could have at least given Gray a shiner.

Such a feeling comes from Gray’s earlier appearances in the film. Aside from the above mentioned incident with the Black waiter, he flirts with Barbara Parker, the Sheriff’s daughter. The Dallas newspapers don’t bother investigating the anonymous rumors Gray spreads about himself. By the time Gray is entrusted with a fortune in jewels to offer for sale, this viewer was half convinced the alleged financier would embezzle the sparklers. Whether Gray doing otherwise is enough to convince other viewers to put this character in the White Hat category will be a matter of disagreement. But let it be noted that this viewer might have found “Flowing Gold” more interesting character-wise if the evil Nelson had the saving grace of being right about Gray’s allegedly disreputable character.

As is, De Grasse’s film winds up leaning into messages that would appeal to the older Faux News demographic. Rural life is preferable to city life. Great wealth is worth enjoying, but the negative social attitudes spawned by possessing great wealth can be avoided. Trashing expensive surroundings is always entertaining. And nothing succeeds like excess for a disaster movie-like finale.

For the rest of us viewers, “Flowing Gold” falls into the amusing but forgettable category.

***

Martin Fric’s Czech silent film “The Organist At St. Vitus Cathedral” may contain such melodramatic elements as a shameful secret and a protagonist whose life goes into the gutter. Yet the resulting film is not itself a melodrama. In fact, it’s a moving tale whose success rests entirely on the shoulders of director/actor Karel Hasler, who rivetingly captures the emotional agonies of the film’s title character.

St. Vitus Cathedral’s elderly organist lives for playing the church’s organ. One evening, his simple bachelor life gets fatefully changed by the sudden suicide of an old friend. Without mentioning the suicide, the organist gives the money entrusted by the dead friend to his daughter Klara, a nun in a convent. He thinks the money delivery marks the end of the affair, but Klara’s yearning to experience life outside the convent leads to the first of many acts that will change the lives of both the young woman and the organist.

Without needing to provide background exposition, Fric aided by Hasler’s performance makes the organist’s actions understandably human. The viewer senses the organist has lived a simple and predictable life. The friend’s suicide unnerves him so badly that he becomes easily swayed by neighbor Josef Falk’s suggestions to bury the body and to pay him to buy his silence. By the time the organist realizes what he has done, he’s already trapped.

Fric’s camera gives Prague a sense of place and weight. Whether it’s feeling St. Vitus’ towers dominate the city skyline or seeing the winding and hilly streets of the city, the visual results will inspire dreams of tourism, not admiration at the craft behind painted backdrops on a soundstage.

Klara’s character arc feels like an intriguing inversion from those undergone by American movie heroines of the time. In American films, innocents such as Klara can wind up rejecting the sinful world for the refuge of the convent. But in this Czech film, Klara’s unauthorized departure from the convent isn’t a source of shame. It’s a necessary evil to achieve her greater aim of experiencing life, whether that’s trying to ignore the flirting of wealthy would-be painter Ivan or getting up the nerve to whack the life out of a store-bought fresh fish. At no point in the film does this former nun ever regret leaving the convent.

Modern viewers have no cause for feeling disappointed that Klara and the organist’s relationship never gets sexual. Aside from the huge age difference getting in the way of such a development, such a viewer’s desire misunderstands the relationship between these two individuals. At this stage in her life, Klara needs a friend who will give her a safe space to adjust to life outside the convent. The organist needs someone who cherishes him for something other than his musical ability. This platonic relationship is frankly what both these individuals need.

Fric’s visual storytelling usually stays in the realm of realistic depiction. On a couple of occasions, though, the director spins and nearly blurs the background image. These two moments, one involving grates and another involving organ pipes, serve as visual shorthand for one of the film’s characters’ either feeling confined or feeling a loss of the work that gave their life meaning.

Ultimately, Hasler’s performance proves key to the film’s success. His character may not have scenes involving over the top visual histrionics. But the actor clearly conveys the internal life of a man who can go from nonplussed confusion to artistic inspiration to sorrowful desperation.

The Silent Film Festival’s description of Fric’s film may be accurate but falls short in intriguing potential viewers to catch this movie. Call “The Organist At St. Vitus’ Cathedral” instead an example of the festival’s strength in discovering and bringing to its audiences entertaining films from countries not normally associated with having a silent cinema history.

***

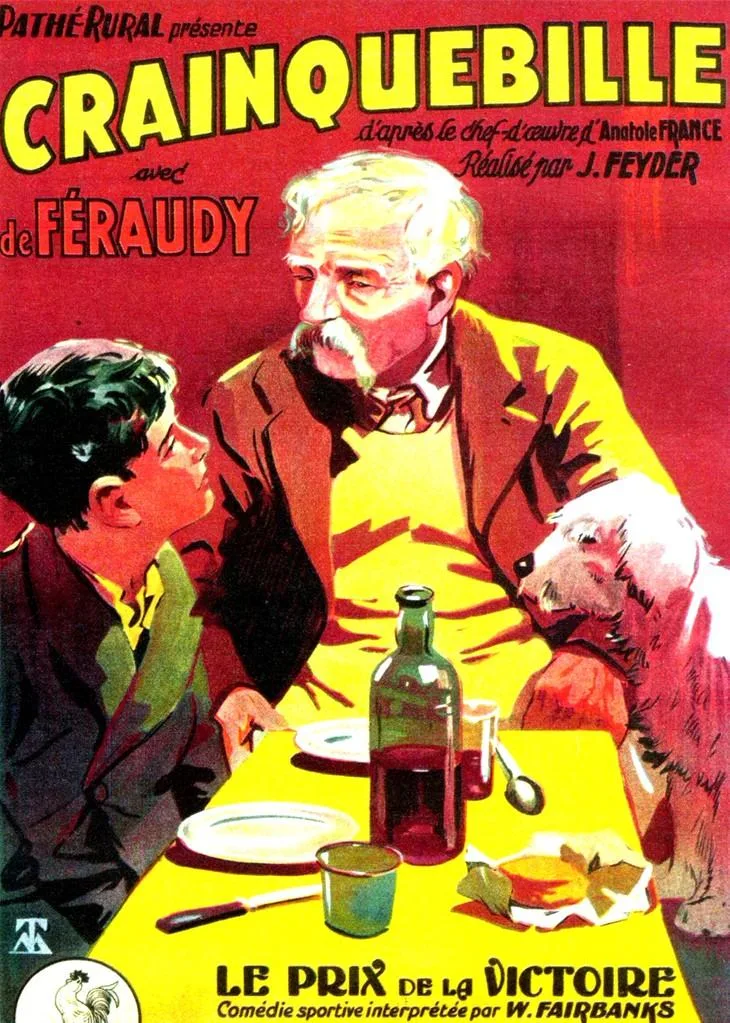

Another must-see at this year’s Silent Film Festival is Jacques Feyder’s “Crainquebille,” an adaptation of Anatole France’s tragicomic novella of the same name. Its less-than-flattering portraits of cops, the criminal justice system, and the petit-bourgeois will resonate with those who regard “polite society” with a baleful eye.

Jerome Crainquebille has sold fruits and vegetables from his street cart to his customers for years. But when shoe store owner Madame Bayard fails to pay the peddler promptly for a purchase, it triggers an absurd misunderstanding which eventually results in Madame Laure and the fruit and vegetable seller’s other customers treating Crainquebille as a pariah.

Feyder’s film may be set in a period long before supermarkets were a thing. But in taking time to acclimate the viewer to the world of Crainquebille and other peddlers like him, the viewer comes to share the lead character’s eventual sense of personal betrayal by the film’s later events. Before the fateful misunderstanding occurs, Crainquebille treats the people he meets kindly. Mouse the newsboy gets the peddler’s protection from bullies. Friend and customer Madame Laure shares with Crainquebille her dream of leaving her disreputable neighborhood and setting up a small farm in the country.

Yet it’s that kind nature that winds up getting the peddler in trouble. He cannot conceive that Madame Bayard would not care about keeping him waiting so long that a traffic jam is accidentally created. Nor can the peddler conceive that Gendarme 64 might be a self-important petty tyrant and not a reasonable man.

Even when he starts being ground down by the French criminal justice system, Crainquebille has no idea how much danger he’s in. He doesn’t notice that his attorney, the womanizing Lemerle, doesn’t even try to mount an aggressive defense. His observations of the trial’s progress feel more like comic bemusement rather than appreciating just how badly he’s being railroaded. Feyder’s visualization of Crainquebille’s observations leads to some wonderful visual gags. Still, any urge to laugh gets tempered by the viewer’s remembering more than a few actual trials where a police officer’s words were given far more credence than they actually deserved.

Ironically, Crainquebille would have been better prepared for post-prison life had he been treated badly while in the state’s custody. But Doctor Mathieu’s anonymous payment of the peddler’s fine and the adequate accommodations of the peddler’s cell lulls him into treating his undeserved imprisonment as a minor inconvenience.

If the object of imprisonment is to provide a negative incentive to commit further crimes, the popular French prejudice against ex-convicts defeats that purpose. Crainquebille’s spirit gets so broken by his former customers shunning him or otherwise betraying him that he starts losing any desire to be a productive member of society. His desperation gets so great that he seeks salvation from Gendarme 64, the cop whose misunderstanding started the peddler’s troubles.

The use of Mouse the newsboy in the film’s finale comes off as slightly problematic. On one hand, the boy’s repaying the older man for his earlier protection. On the other hand, it’s unclear whether this optimistic note is intended as a viewer-attracting sop against a more logical downbeat ending. Whatever the motivation, this mostly successful adaptation (i.e. the Dr. Mathieu’s nightmare sequence is fun but doesn’t seem to have a dramatic payoff) is still worth a watch and maybe even a hunt for a translation of France’s original story.

(“Flowing Gold” screens at 1:00 PM on July 14, 2023 with live music by Utsav Lal. “The Organist At St. Vitus Cathedral” screens at 3:00 PM on July 15, 2023 with live music by Maud Nelissen. “Crainquebille” screens at 7:00 PM on July 15, 2023 with live music by the Stephen Horne Ensemble. All screenings take place at the Castro Theatre (429 Castro, SF).

For further information about the films reviewed and to order advance tickets, go to https://silentfilm.org/festival-2023-schedule/ .)

Filed under: Arts & Entertainment