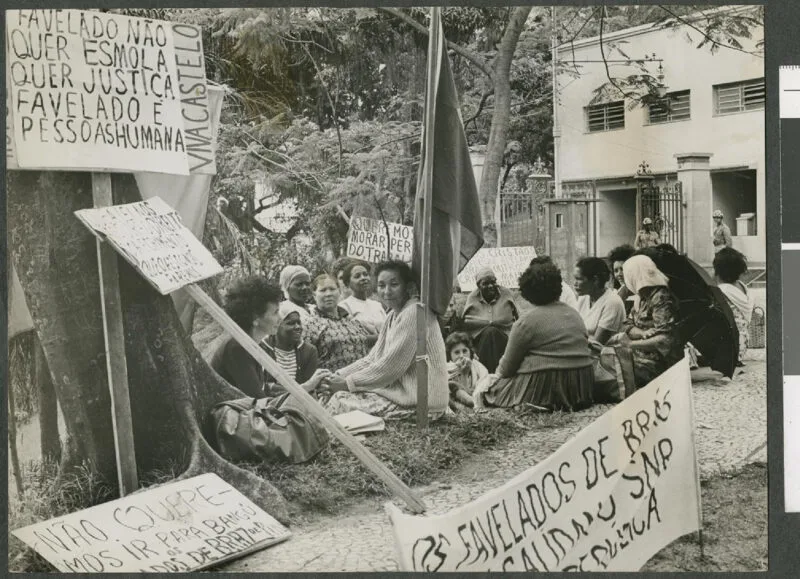

Organization that gathered inhabitants associations had their representatives arrested and was considered subversive in the 1960s | Image: Correio da Manhã Archive/National Archive

This article, written by Lucas Pedretti and Marcelo Oliveira and edited by Thiago Domenici, was originally published on the Agência Pública’s website on November 6, 2023. An edited version is republished here through a partnership agreement.

On November 6, 2023, the Federation of Favelas Associations in Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ) and the Public Defender’s Office of the Union (DPU) took unprecedented action with the Amnesty Commission of the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, demanding that the Brazilian state recognize and give compensation for the persecution suffered during the military dictatorship (1964–1985). The request was made based on documents made by the dictatorship’s arms of repression.

The Amnesty Commission was created in 2002, and has now recognized and compensated for over 50,000 cases of individuals who suffered rights violations for exclusively political reasons. Weakened during the Bolsonaro government, the entity was then reconstituted in early 2023 and, from among the proposed changes, established a new rule that associations and collectives can also request amnesty.

In the first request for collective reparations to the Amnesty Commission, made by the DPU, the federation seeks recognition that the serious human rights violations conducted by the military were not restricted to individual cases and that violence was also inflicted on the federation as a whole, based on race, class, and territory.

In the 28-page file, signed by the public defender Bruno Arruda, the federation and the DPU included several pieces of evidence to support the request and demand a set of symbolic reparations, so opening a new chapter in Brazil’s transitional justice.

The policy of forced evictions

The DPU is restarting work that began with the Rio de Janeiro State Truth Commission (CEV-Rio), which, in its final report, published in December 2015, dedicated an entire chapter to human rights violations perpetrated by the dictatorship in the favelas. According to CEV-Rio, one of the main forms of violence was the policy of forced evictions, which reportedly affected more than 140,000 people between 1962 and 1973. For the DPU, this was “a systematic process of serious human rights violations”.

The project to permanently eradicate the favelas from the Rio de Janeiro skyline began in 1962, when the governor of the former state of Guanabana was Carlos Lacerda. Historian Marco Pestana noted:

Over decades, entities linked to real estate and construction capital prepared studies in favour of removing the favelas, always highlighting that the focus should be the South Zone and Tijuca.

For this project to become public policy, specific circumstances were necessary, which came about when Carlos Lacerda, an opponent of [national president] João Goulart, became governor of Guanabara [state].

According to the researcher, the coup and the dictatorship then intensified and radicalized the evictions, with more public agents and money becoming involved.

In 1963, the Federation of Favela Associations of the State of Guanabara (FAFEG) was founded. (While Brazil’s capital migrated from Rio to Brasília, for a while, the city included Guanabara state).

“The idea was to make an organization where the protagonists were the favela residents themselves,” explained historian Juliana Oakim, who worked with CEV-Rio. “In mid-1962, with the changes in policy on favelas, FAFEG appeared as an attempt by the residents to organize themselves to face what was to come.”

With the end of Lacerda’s government in 1965, the forced evictions were temporarily stopped. In 1968, the dictator Costa e Silva created the body Coordination of Housing of Social Interest in the Grande Rio Metropolitan Area (CHISAM). The new body, linked to the Ministry of the Interior, restarted the project.

“From 1968, the policy of evictions stopped being just a state government initiative and became a policy of the [national-level] military regime itself,” Oakim explained, and FAFEG responded with its second congress and the slogan “urbanization, yes; eviction, no.”

In January 1969, the period’s most infamous evictions began, such as those of the favelas around the Rodrigo De Freitas lagoon, an area which now has apartments valued at millions of reais (local currency). Whole communities were broken up, with the forced displacement of thousands of people. It was in this context that a second attack against Fafeg and its leaders took place.

In February of that year, the leaders of the Dragas Island residents’ association were kidnapped and reported missing. FAFEG then mobilized and connected the motive behind the kidnappings to the residents’ resistance, and four of its leaders were arrested: Vicente Ferreira Mariano, Abdias José dos Santos, José Maria Galdeano and Ary Marques de Oliveira. As well as arrests, state violence against the residents began to include fires, such as the one in the favela of Praia do Pinto, on Mother’s Day in 1969, which then paved the way for the community’s complete eviction.

Praia do Pinto Favela | Image: Correio da Manhã Archive/National Archive

Control of the federation

The arrests of leaders of residents’ associations and FAFEG, who resisted evictions, came with an escalation of the dictatorship’s repression. Documents included in the petition for amnesty indicate that, even after these large-scale evictions, the persecution continued.

After some time, leaders attempted to re-energize the federation by taking advantage of the political opening and the rise of social movements across the country. One of these leaders was Irineu Guimarães, elected in 1979.

The repression went after a new target. The Department of Political and Social Order (DOPS) described Guimarães as an “activist — in revolt against the current constitutional regime.”

In July 1980, Guimarães was arrested and interrogated in a police investigation.

In 2012, he was given political amnesty by the Amnesty Commission. In the report on the vote that approved the reparations, the body attested that he had been the target of political persecution. Like him, other leaders of FAFERJ participated individually in the Amnesty Commission and were recognized as having been politically persecuted: Etevaldo Justino, arrested in 1964, and Abdias José dos Santos, arrested in 1969, also had their requests accepted.

Collective amnesty

Now, FAFERJ, the organization which succeeded FAFEG, marking its 60th anniversary, seeks recognition that it was targeted by the regime.

“Favelas do not usually appear in the pages of textbooks, in the established historiography and in official records,” noted Derê Gomes, the organization’s institutional relations coordinator, who is also a historian and was in charge of preparing the request to the DPU. “For this reason, it is essential that an organ of the Brazilian state can officially declare that the dictatorship systematically repressed favela residents and their initiatives for self-organization, such as FAFERJ.”

The mechanism for collective amnesty is new for the Amnesty Commission, and to date, no such request has gone to judgement. Eneá De Stutz E Almeida was appointed early this year as the commission’s new president. She explained that this idea had already been discussed before 2016 regarding cases of indigenous territories, but the change only came this year with the commission resuming.

Unlike individual cases which come before the Amnesty Commission, requests for collective amnesty will not receive any kind of compensation, but only symbolic forms of reparation. In its request, FAFERJ demands the “public recognition of the human rights violations perpetrated on marginalized communities, in this case, the political persecution of FAFERJ” and an “official apology from the Brazilian state to FAFERJ and the residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, for the political persecution committed during the period of Brazil’s dictatorship”.

Derê Gomes, FAFERJ coordinator, with the president of the Amnesty Commission, Eneá de Stutz e Almeida | Image: Guilherme Moraes Camilo Alves

“We are pushing the State to discuss, remember, and compensate for the violence caused to an entire community through a public policy aimed at silencing social demands,” said the public defender Bruno Arruda, author of FAFERJ’s collective reparations request.

To widen the scope of this process, Arruda created the Observatory of Memory, Truth, and Justice at the DPU. The FAFERJ case is the Observatory team’s first project. “There is still plenty of room to progress on the topic of transitional justice within the judiciary,” and the observatory allows it to make partnerships with civil society to push forward the debates necessary to advance Brazilian transitional justice, he said.

Derê Gomes also observed that “while the rest of society celebrated the return of democracy, the favelas continued suffering human rights violations.”

“Drawing attention to the persecution of the favelas during the dictatorship is a way of showing that, for us, state violence is the norm, not the exception. As such, it is essential to connect the current killings of Black and favela youth with what has happened in other periods of history,” he says.