Freed people, during and after slavery, tried to compel the government to provide restitution for slavery, to provide at the very least a pension for those who, along with generations of their ancestors, had spent their entire lives working for no pay. They filed lawsuits and organized to lobby politicians. Unfortunately, every effort failed.

The closest this country has ever gotten to delivering reparations was during the period known as Reconstruction. For 12 years after the Civil War ended, Congress passed amendments abolishing human bondage, preserving equal protection, and guaranteeing Black men the right to vote. There were millions of Black people liberated, but none of them had a cent to their name. They wanted, and deserved, property so they could work, and support their families. Like now, they understood that land in this country meant wealth, and, more importantly, independence. They weren’t looking for a handout but simply asked for land to work until they could earn enough money to purchase it.

Special Field Order 15 was issued, providing for the distribution of hundreds of thousands of acres of former Confederate land in forty-acre tracts to newly freed people along coastal South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. This became known as “forty acres and a mule.”

Four days after the order was issued, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and racist Vice President Andrew Johnson took over. Immediately, he reneged on the forty-acres promise and overturned the order. Just like that, the land that had been given was seized and given back to the traitors. With that went the only real effort this nation ever made to compensate Black Americans for 250 years of chattel slavery.

We are still living with the legacy of choices made for us back then. As scholar Henry Louis Gates said, “Try to imagine how profoundly different the history of race relations in the United States would have been had this policy been implemented and enforced; had the former slaves actually had access to the ownership of land, of property; if they had a chance to be self-sufficient economically, to build, accrue and pass on wealth.”

A bill has been brought before the House of Representatives in every session since 1989, but has never gained enough support in Congress.

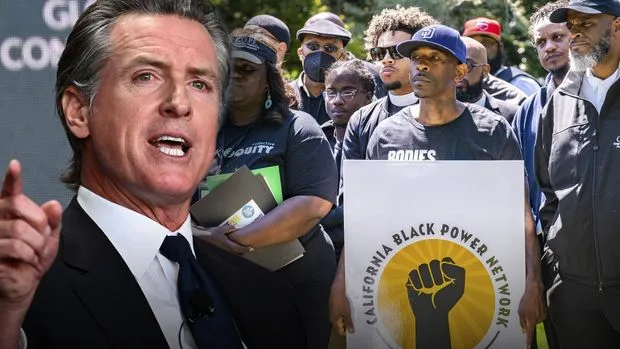

Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the topic of reparations has gained new traction. Since then, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a law establishing a state task force to study historic and systemic racism and develop communications to attempt to right centuries of wrongs. This legislation is the first of its kind in the nation. The California Reparations Task Force voted in May 2023 to approve a 1,000-page document, including more than 200 recommendations for how to undo centuries of unfair treatment for Black Californians, especially descendants of enslaved people.

California was not even a slave state, but nearly 4,000 enslaved Black people were taken there between 1850 and 1860 to work in gold mines. Many of those Black people settled in California after slavery ended, and they were able to buy land. Unfortunately, they still faced discrimination, seizure or theft of their land, over-policing, and housing segregation.

For Black residents in California, qualifying for any cash reparations will not be easy. Determining lineage will be challenging, and in some cases, impossible. It will have to be traced to a person who had been enslaved or who lived in the United States prior to 1900.

Other states, such as Illinois and Minnesota, have examined what reparations could look like. In Evanston, Illinois, a 2020 report commissioned by the city details how the city continued discriminatory practices toward Black residents. The report also highlights that Evanston banks typically refused mortgage loans to Black residents seeking to buy homes in predominantly white neighborhoods. When the city’s Restorative Housing Reparations program opened online applications in September 2022, officials received more than 600 applications.

St. Paul, Minnesota, has also taken steps towards a reparations package for Black residents. After the city apologized for its role in the institutional and structural racism experienced by its Black residents, officials established an advisory committee to create a framework for a reparations commission. Later, the advisory committee recommended direct cash payments to eligible Black residents and the establishment of a permanent reparations committee focused on implementing reparations to address racial disparities in housing, healthcare, education, employment, and more.

Many non-Black people oppose reparations to Black people, stating neither they or their ancestors had anything to do with the ways in which Black people have been oppressed. But as a nation, we have to make amends to Black citizens who have been harmed by past policies of our governments. Acknowledgment is the first step. Apologies, memorials, and financial reparations continue this process.

Reparations are a way of making the country whole by partially remedying the inherited inequalities that still plague Black people. They are a way of saying that Black people are, finally, equal citizens of the United States of America and therefore deserving of its privileges and protections. Racial reckoning in this country includes reparations.

The truth is, slavery enriched white slave owners, as well as their descendants. It fueled this country’s economy but suppressed wealth-building for enslaved people. This continues to be a reality for Black people today. The United States has a responsibility to compensate descendants of enslaved Black people for their labor. The federal government has a responsibility to compensate for the lost equity from anti-Black practices such as redlining and other discriminatory practices that have robbed Black people of opportunities to build wealth.

This is about righting the wrongs in the ways in which Black people were treated during the period of institutionalized racism. There are obstacles to overcome in every state, yet I believe it begins with empathy. Just as California, Illinois, and Minnesota have determined ways to implement reparations, all other states can do so as well. This means academics and policymakers can frame discussions surrounding reparations in line with projects already in place for housing, jobs, education, healthcare, and wealth management. Taking these steps can facilitate, in every state, a long-overdue plan to atone for this nation’s original sin.