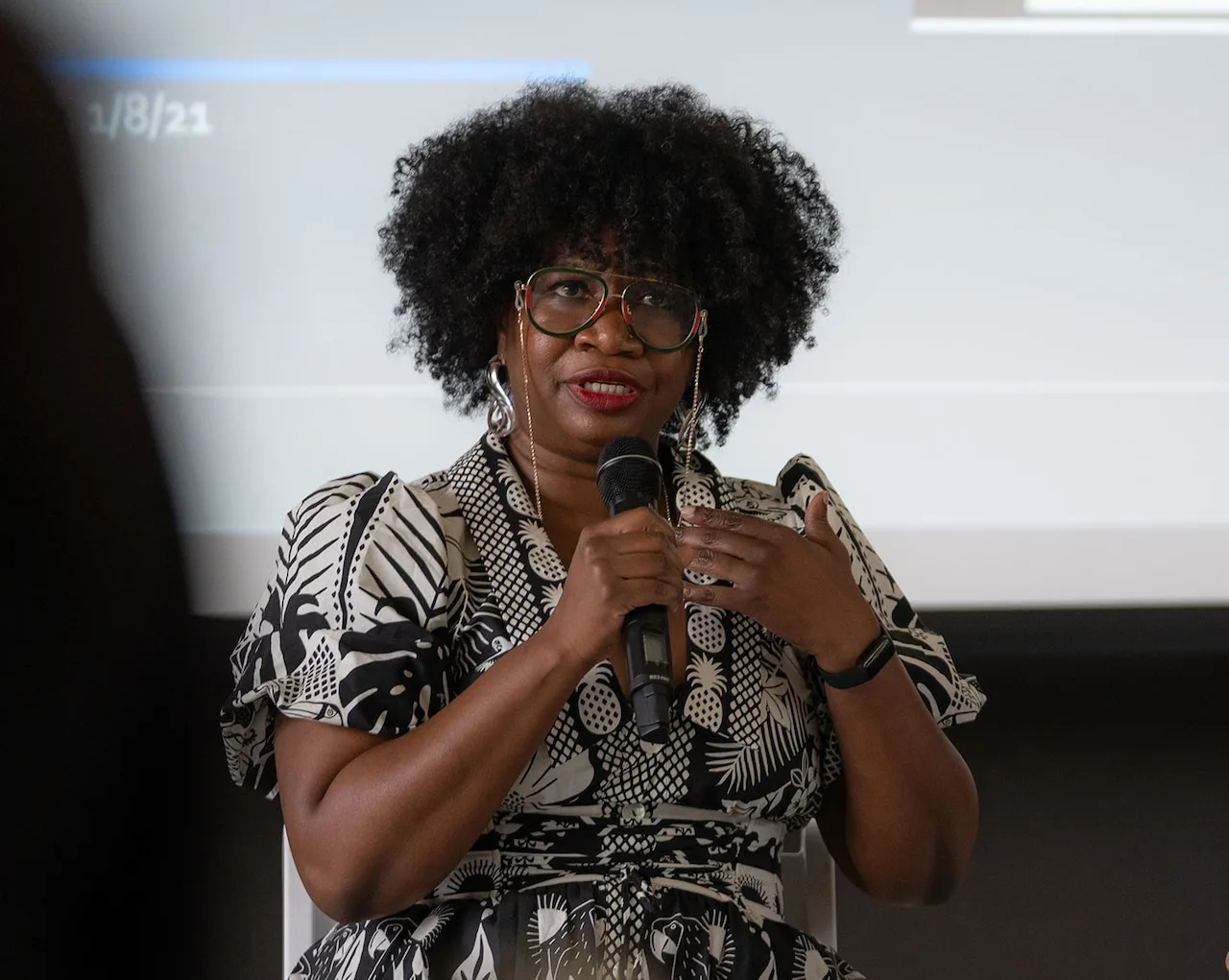

CLEVELAND, Ohio — As an historian and self-described reproductive justice advocate, Deirdre Cooper Owens sees the roots of present-day disparities in health care when she looks at the past.

Beginning in the 17th century, physicians and scientists held the erroneous belief that Black women didn’t experience the pain of childbirth as white women did, said Cooper Owens, author of the 2018 book “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology” ($27.95, University of Georgia Press).

“The sad reality is, even in studies from the 21st century, you find medical practitioners at every level who believe Black people don’t experience pain in the same ways that white people do,” Cooper Owens said. “That’s a legacy we need to get rid of, because it is scientifically, biologically false.”

Owens will discuss the intersection of race and health care as the keynote speaker at the first-ever Black Maternal Health Equity Summit, Sunday, April 14 at Cleveland State University.

The Black Maternal Health Equity Summit is noon to 4 p.m. at the CSU Student Center Glasscock Ballroom, 2121 Euclid Ave., Cleveland.

Cost is free but registration is required. Deadline for registration is Tuesday, April 9.

The event — sponsored by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Northern Ohio at Case Western Reserve University — strives to advance health equity for Black mothers and, consequently, all mothers, said Gelise Thomas, director of research health equity for the collaborative, and summit co-organizer.

The collaborative includes CWRU, the Cleveland Clinic, MetroHealth System, University Hospitals, the Louis Stokes Veterans Administration Medical Center, Northeast Ohio Medical University, and the University of Toledo. The collaborative serves as a catalyst for research aimed at enhancing health in Northern Ohio and beyond.

“There will be learnings from this summit that will be applicable to all mothers, but we’re seeing the worst outcomes for Black mothers, so why are we not being more pointed in our research and resources towards that end?” Thomas said, referring to the high rate of maternal deaths among Black women.

Summit participants will enjoy brunch while listening to speakers from CSU, CWRU, the Center for Community Solutions, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies.

Cleveland-area grassroots organizations focused on maternal and infant health will make presentations. Summit participants also will hear from mothers sharing their birthing stories, Thomas said.

“One of the faults of research is that we’re not talking to the people who are closest to the problem,” Thomas said.

Thomas hopes the summit will inspire more research into Black maternal health. The Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Northern Ohio can award up to $7,500 toward research aimed at solving health disparities, Thomas said.

Black maternal and infant health affects our entire society, Thomas said.

“If you hire Black mothers, or if you are funding Black mothers who are starting businesses, you need to understand what they’re up against, and the ways that you can either contribute to the solutions or contribute to the problems,” Thomas said.

In 2021, the maternal mortality rate for Black women was 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, 2.6 times the rate for white women, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Infant mortality was 10.5% for Black babies, 7.6% for American Indian and Alaska Native babies, 4.8% for Hispanic, 4.4% for white infants and 3.4 for Asian infants, according to a March CDC report looking at infant mortality and maternal characteristics from 2019 through 2021.

The infant mortality rate was 9.3% when Black mothers started prenatal care in the first trimester, and 16% when Black mothers received prenatal care in the third trimester or had none, the March CDC report said. For white mothers, the infant mortality rate was 3.6% for those who started prenatal care in the first trimester, and 10.5% when white mothers received prenatal care in the third trimester or had none. The data represented 2019-2021.

Owens returns to Cleveland

In her work as a historian, Cooper Owens strives to amplify the past to provide context for how current society can do better.

“I am a Black woman. I experience the legacy of anti-blackness and if I can do my part to push back, to resist, to provide education, that’s something that I’ve signed up to do, and I do it willingly,” Cooper Owens said.

During her upcoming remarks at the equity summit, Cooper Owens will talk about the linkages between past and present that affect health care for Black women. She will also discuss ways that women can advocate for themselves and help to dismantle harmful practices.

Cooper Owens previously spoke at a collaborative-sponsored event last fall. She made such an impact that Thomas was inspired to bring her to Cleveland again, this time for a larger event.

Many Americans believe racism in health care is a present-day problem, according to a KFF Survey on Racism, Discrimination and Health released in late February.

Large majorities of adults say racism is at least a minor problem in health care, U.S. politics, criminal justice, and other U.S. institutions, according to KFF, a nonprofit organization focused on health policy that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente and is not a foundation.

Black adults, other people with darker skin color and those with experiences of discrimination are less likely than their counterparts to trust health care providers, the KFF report said.

It’s important that the summit will focus on solutions to move society closer to the day when all patients are treated equitably and fairly, despite income, skin color or disability, Cooper Owens said.

“If we simply had a practice of treating patients equitably, that could move us forward in profound ways, but what we’re finding is a lot of folk refuse to do that,” Cooper Owens said.

Julie Washington covers healthcare for cleveland.com. Read previous stories at this link.