Childhood experiences have an enormous impact on children’s long-term societal contributions. Experiencing childhood maltreatment is associated with compromised physical and mental health, decreased educational attainment and future earnings, and increased criminal activity. Child protective services is the government’s way of endeavoring to protect children. Foster care consequently has large potential effects on a child’s future education, earnings, and criminal activity. In this post, we draw on a recent study to document disparities in the likelihood that children of different races will be placed into foster care.

There are large racial disparities in involvement with child protective services (CPS). Although 28 percent of white children experience an investigation by CPS before age 18, the majority of Black children (53 percent) do (Kim et al., 2017). Black children are likewise twice as likely to spend time in foster care than white children (10 percent vs. 5 percent). Racial discrimination in this domain could exacerbate inequalities in many long-term outcomes. Yet racial disparities could also reflect differences in underlying risk of future child maltreatment. Attributing well-documented racial disparities to discrimination is thus a challenging task.

In a recent working paper, we conduct the first quasi-experimental study of racial disparities in the child protection system. We examine “unwarranted” racial disparities: that is, disparities in foster care placement rates among children who have an equal potential for being maltreated in the future if left at home. This is a natural measure of discrimination, since protecting children from future maltreatment is the sole reason why CPS decision-makers would place a child in foster care.

The difficulty in measuring unwarranted racial disparities is that a child’s potential for future maltreatment in the home is only partially observed: we can see future maltreatment only among children who were actually left in the home. For children who were placed into foster care, we cannot observe the subsequent maltreatment that would have occurred if they had been left at home. Thus, we cannot directly condition disparities on future maltreatment potential.

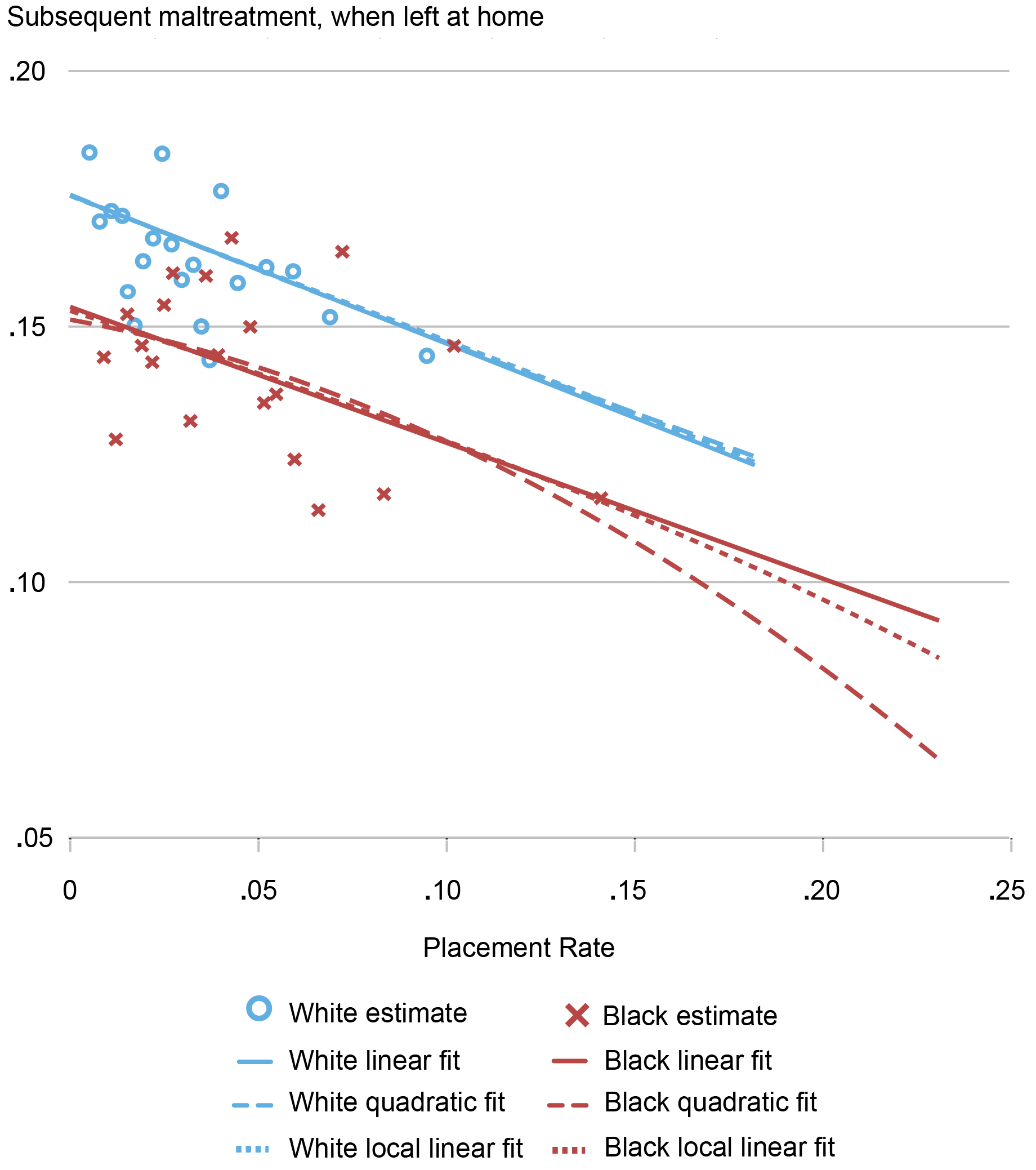

To overcome this measurement challenge, we leverage the quasi-random assignment of case investigators in Michigan—the setting of our study. Since each investigator receives a random subset of cases, we can ascertain their race-specific likelihood of placing a child in foster care based on their behavior in the cases assigned to them. Furthermore, by looking at the subsequent maltreatment rates of children assigned to investigators with very low placement rates, we can infer the average rates of maltreatment potential across all white and Black children in the state (see the chart below). Knowing these rates, we show, is enough to overcome the challenge of not observing future maltreatment potential of children placed into foster care.

Investigators’ Rate of Placement in Foster Care and the Subsequent Maltreatment Rates among Children Left at Home

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows a binned scatter plot of foster care placement rates and subsequent maltreatment rates, among children left at home, across different quasi-randomly assigned investigators and by child race. The vertical intercept of each line-of-best fit estimates the average maltreatment potential among all children of that race.

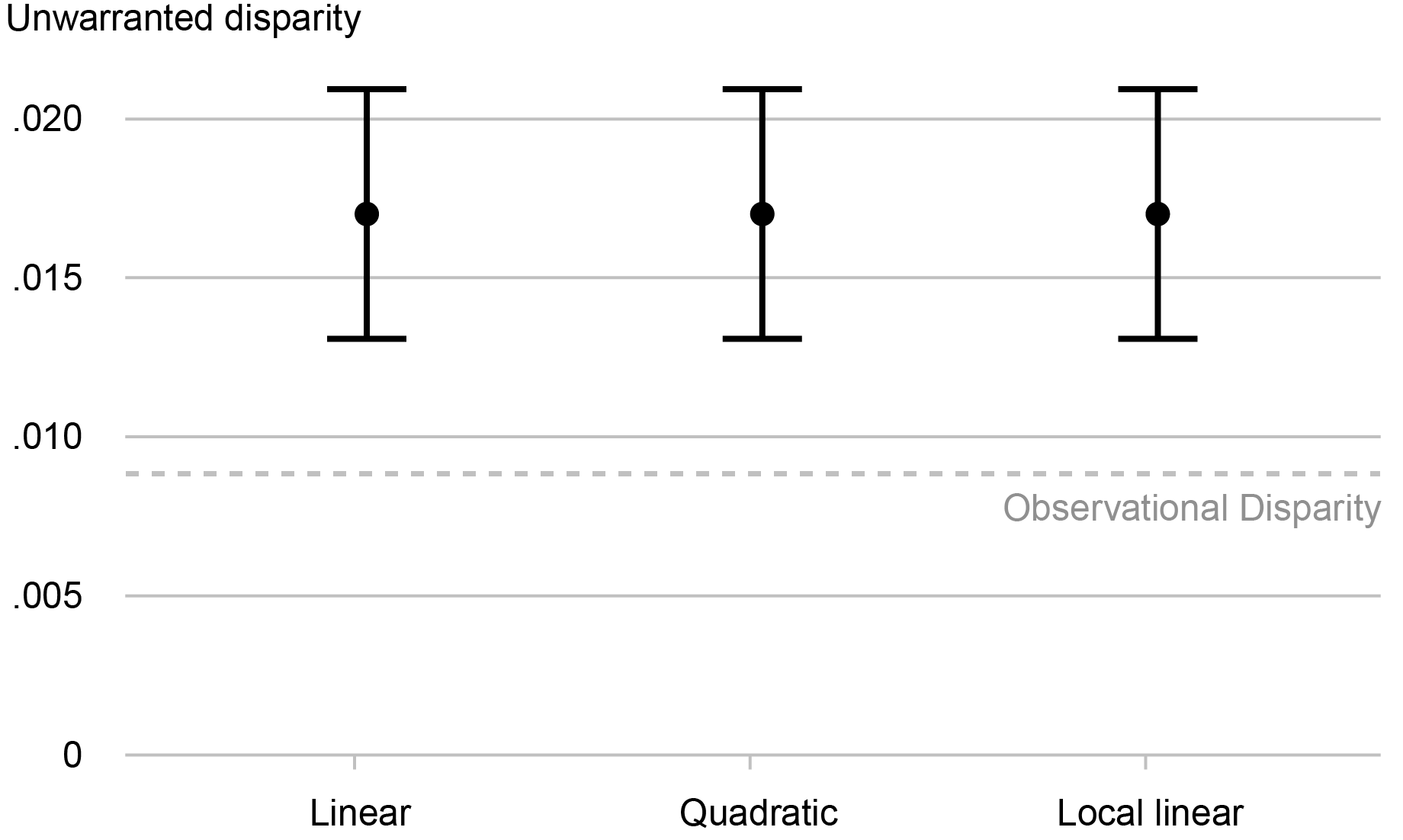

Applying this approach, we find significant evidence of unwarranted racial disparity in foster care placement. Black children are 50 percent (1.7 percentage points) more likely to be placed into foster care than white children who have the exact same potential for experiencing subsequent maltreatment if left at home. Accounting for the risk of subsequent maltreatment is crucial: estimates of unwarranted racial disparity are nearly 90 percent larger than the placement disparity from an observational analysis that controls for child and investigation traits alone (see the next chart).

Unwarranted Racial Disparity Estimates, Relative to Observational Disparity

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows estimates of unwarranted racial disparity for each of the three estimation approaches in the first chart above, along with an observational disparity which controls for child and investigation traits (dashed horizontal line). 95 percent confidence intervals are indicated by whiskers.

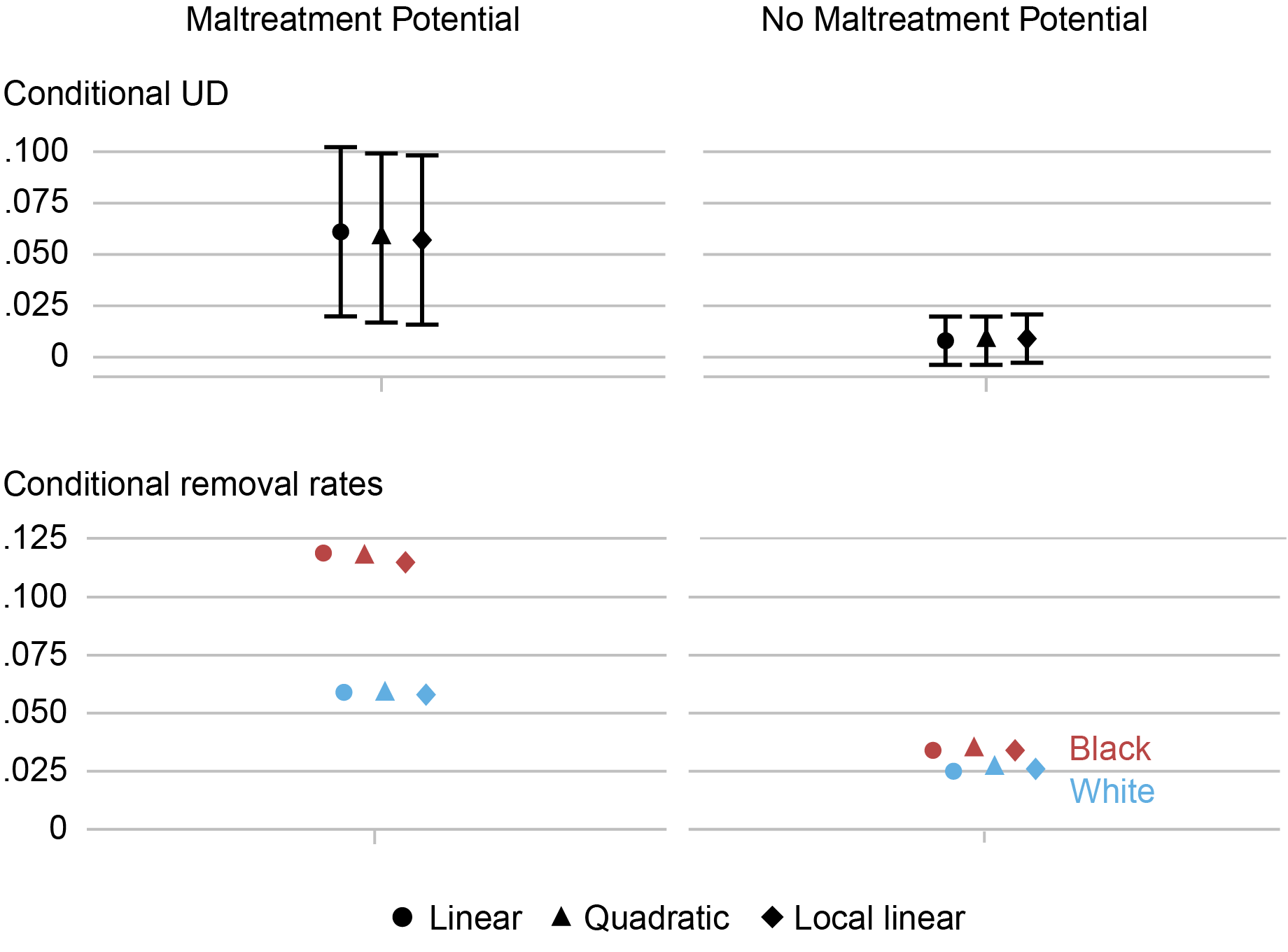

We further consider whether unwarranted racial disparities arise among children who are likely to be safe if left at home, or among those likely to experience maltreatment if left at home (see the chart below). We find that racial disparities in foster care placement are driven by children with a potential for subsequent maltreatment if left at home. Black children who would likely experience maltreatment if left at home are placed in foster care at twice the rate of white children in this subpopulation (12 percent versus 6 percent). In contrast, the foster care placement disparity is small and statistically insignificant in the subpopulation of children who are likely to be safe if left at home.

Unwarranted Racial Disparities and Foster Care Placement Rates for Children with and without Maltreatment Potential

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows estimates of unwarranted racial disparity and foster care placement rates for each of the three estimation approaches in the first chart above, separately for children with and without future maltreatment potential. 95 percent confidence intervals are indicated by whiskers.

A higher placement rate among children who are likely to be maltreated if left at home may offer protection to those children, particularly if foster care improves long-run outcomes. Prior research in our specific setting finds that foster care improves outcomes for both Black and white children at risk of subsequent maltreatment if left at home: it lowers the likelihood of subsequent maltreatment and adult criminal justice contact while also improving educational outcomes. Together, this evidence suggests that higher placement rates among Black children may have a protective effect. Indeed, one might worry that white children are being “under-placed” relative to Black children.

There are active policy debates over ways to reduce racial disparities in foster care placement—as well as overall usage of foster care services. We find that lowering the foster care placement rate of Black children to equalize placement rates across races, as some have advocated for, would lead to a 7 percent increase in the number of Black children who are subsequently maltreated when left at home. On the other hand, using family preservation services that aim to reduce maltreatment while keeping families together may offer a possible solution. Greater efforts to increase outreach and take-up of these services among Black families may reduce the placement disparities while improving family well-being. Given the far-reaching consequences that child maltreatment and foster care can have—on physical and mental health, educational attainment, future earnings, and criminal activity—reducing racial disparities in these early-in-life outcomes can impact future societal inequities.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

E. Jason Baron is an assistant professor of economics at Duke University.

Joseph J. Doyle Jr. is the Erwin H. Schell Professor of Management and Applied Economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Peter Hull is a professor of economics at Brown University.

How to cite this post:

Natalia Emanuel, E. Jason Baron, Joseph J. Doyle Jr., and Peter Hull, “Racial Discrimination in Child Protective Services,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 16, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/10/racial-discrimination-in-child-protective-services/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).