By Barbara Noe Kennedy,

Barbara Noe Kennedy

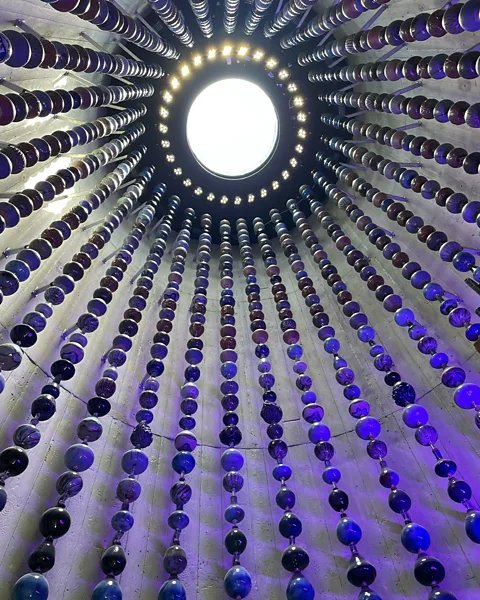

Barbara Noe KennedyThe stout, jug-like building rises 35ft above the greenery of Arlington, Virginia’s Metropolitan Park, a green, path-laced oasis set amid Amazon’s new HQ2 headquarters. Constructed from 5,000-odd red bricks, the structure feels both industrial and earthy, and stepping inside the small space reveals hundreds of glistening, glazed ceramic bulbs cascading from above in waves of blue, green and brown.

This is Queen City, an art installation paying homage to the 903 African American residents of the eponymous all-Black community, as well as the surrounding East Arlington neighbourhood, who were forcibly removed from their homes in the early 1940s to make way for the construction of The Pentagon.

“What they did to us was an atrocity,” said 93-year-old Dr William Vollin, who remembers his childhood in Queen City before he and his family were kicked out. “There was an alleyway with small houses on each side. We had a Black fire department, churches, barbershops, all kinds of businesses,” he said, recalling how he and his friends used to play and walk to school together.

And while there was no running water or electricity common in white neighbourhoods at the time, Queen City residents made do in their tight-knit community. “It was like one big family,” Vollin said.

Two and a half miles away at the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington, Queen City’s little-known story is highlighted through photos and artefacts. According to Dr Scott Taylor, a third-generation Arlingtonian and the museum’s president, the lost “city’s” story starts at Arlington House, the Neoclassical mansion established in the early 1800s by John Parke Custis, the son of Martha Washington and her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. Enslaved individuals from George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, built Arlington House before working on the property and in the home. General Robert E Lee, who in 1831 married Mary Custis, heiress of Arlington House, lived here in the years leading up to the US Civil War. After joining the Confederacy, Lee left, never to return. (After many years of focusing on the Custis-Lee story, Arlington House recently has been reimagined to encompass the voices of African Americans who lived and laboured there, too.)

Alamy

AlamyAfter the Emancipation Proclamation of 1 January 1863 freed enslaved people in Confederate states, the federal government established Freedman’s Village on the Arlington House property (which would later become Arlington National Cemetery). The planned community, with clapboard houses, schools, churches and roads, became a thriving village for formerly enslaved workers. Reformer and writer Frederick Douglass often visited; and abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who lived in the village for a year and a half beginning in 1864, advised villagers on their rights.

At that time, “Arlington was 75% to 80% Black,” Taylor said. “There was so much Black activity then. People were learning to read and write. They were buying property, starting businesses. John Syphax [an African American politician born free in Virginia] became a delegate. This scared [white] people – that’s why [the federal government closed] Freedman’s Village.”

By 1900, the thriving village had been dismantled, with few home and business owners fairly compensated. Today, little remains, other than a historical plaque in Foxcroft Heights Park overlooking Arlington National Cemetery, near its original location.

Many former residents left for other Black neighbourhoods in Arlington or Washington DC. In 1892, Mount Olive Baptist Church, which was founded in Freedman’s Village, bought two acres just down the road and sold lots to ousted congregants. Twelve years later, a developer bought 27 more acres. By 1940, more than 200 African American households lived in this new community, which became known as East Arlington. (Queen City was officially a 4.5-acre area within East Arlington, though the whole area is often referred to as Queen City.)

Barbara Noe Kennedy

Barbara Noe KennedyBut with World War Two looming, the United States required a new military headquarters. The War Department was renting 17 buildings across Washington DC and they needed to consolidate. Federal eyes fell on nearby Arlington, and the fate of the area’s African American community was in jeopardy once again.

At first, only the Pentagon building went up, and Queen City residents watched in fascination. They were not told until the very last moment – in early February 1942 – that they were losing their homes to eminent domain for the construction of roads and parking areas for the Pentagon’s 35,000 employees. “They were given weeks to find a place to go,” said Alfred Taylor. “Then they burned their houses to the ground. The real damage is that it broke up homes and families. They had nowhere to go.”

“We scattered all over the place,” Vollin said. “Many of my buddies I never saw again.” Some went to friends and families, or they moved north or south. After being contacted by a lawyer hired by residents, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt secured temporary trailers, where some, including Vollin’s family, lived in the Arlington neighbourhoods of Johnson’s Hill (today’s Arlington View) and Green Valley. “The trailer camp was filthy, with a common filthy bathroom where people took showers,” he said, remembering how the so-called temporary structures sat on mud flats. “It was just awful.”

Alamy

Alamy“We stayed there a couple of years,” Vollin added. “Then they moved us to another trailer camp in Green Valley. And they finally built some new project homes, where my family moved.”

Despite the fact that Vollin went on to become a successful educator, he has never forgotten how his family and others were treated. “In my research,” he said, “eminent domain indicates that when they build, they’re supposed to enhance an area. But they used eminent domain to destroy an area – the families, the businesses, the hopes and dreams. I deem that as an atrocity.”

For many Americans, however, Queen City’s story remained unknown until recently, when artist Nekisha Durrett created the eponymous installation. She was researching art ideas for Amazon’s new headquarters and stumbled upon the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington’s display about the vanished community that once stood here. “Everyone knows how quickly the Pentagon was built, in record time,” she said. “It’s never mentioned there were people whose lives were upended in order for this to happen.”

Durrett said learning the actual number of people affected made her imagine each of those 903 human lives that were forever changed. “I wanted to make that number,” she said. “It’s not an insignificant number.” After consulting with historians like Dr Scott Taylor – whom she called “a wealth of knowledge” – and meeting descendants of Queen City residents, an idea began to crystallise.

Barbara Noe Kennedy

Barbara Noe KennedyShe visualised the displaced community as individual vessels and decided to use pottery as her material. “Clay and brick production was a big part of Arlington’s history,” she said. “[Arlington] was, at one time, the largest producer of bricks in the country. And there were brickyards over there, where many of the African American men who lived in those communities worked.” Vollin’s father and grandfather, in fact, were among the workers there.

Durrett explained that while the artwork is open to interpretation, the brick exterior is meant to evoke a well: “There was no running water in Queen City at the time, and young children were charged with getting fresh water from a nearby spring for their families. That lack of resources led me to think of this space that I wanted people to inhabit as a well. And those ceramic vessels would take on shapes of drops of water.”

Visiting the art installation one June afternoon, I chatted with several groups of people who had previously never heard about Queen City. “I love [how the installation is] continuing to tell the story,” said Margot Eyring, an artist and former professor who has been involved in racial justice work for more than 45 years. “It’s allowing beauty to speak the truth about hard things. Hopefully it will help people understand how policy affects people.”