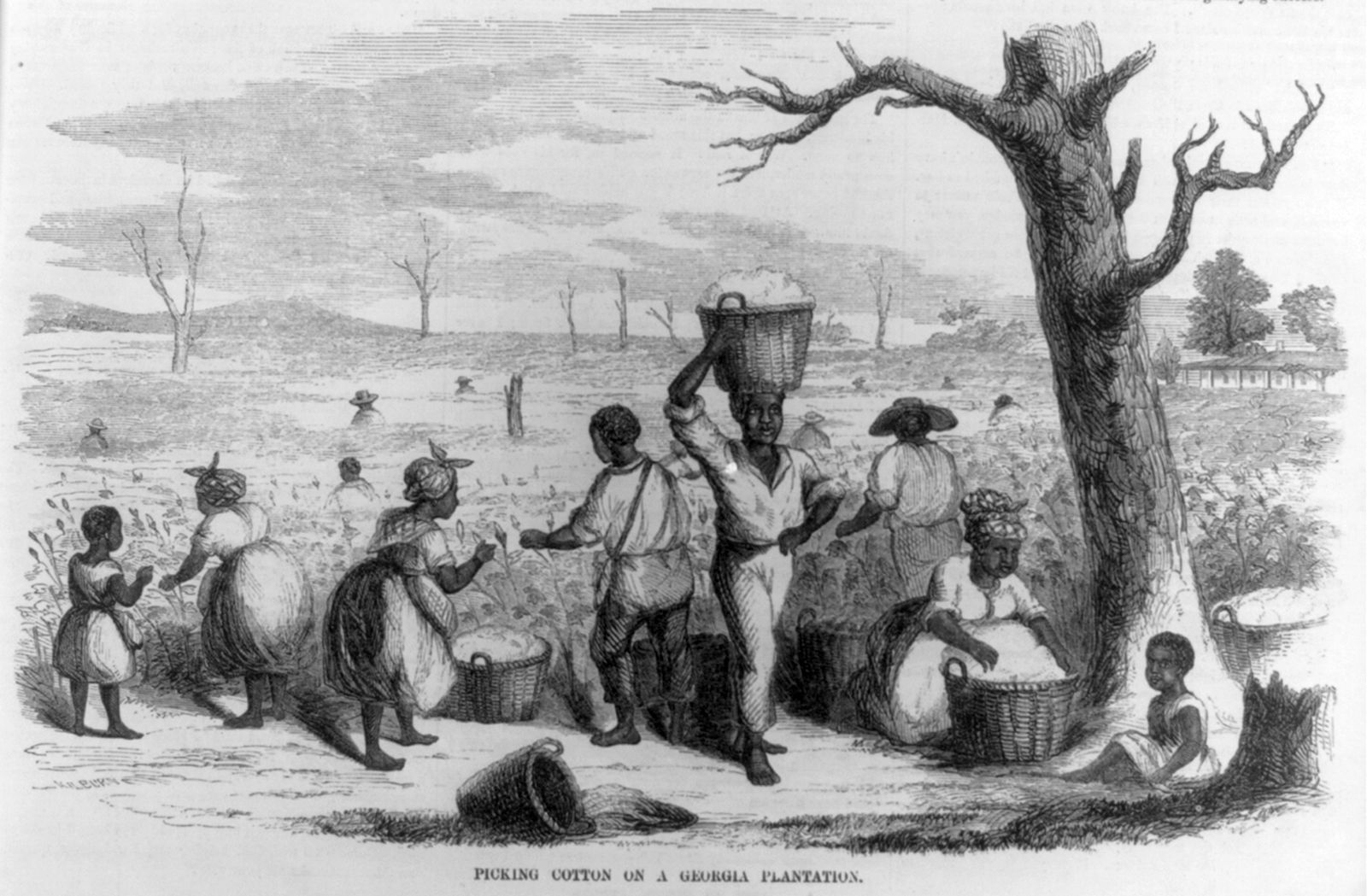

Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (LC-USZ62-76385)

To access extended pro and con arguments, sources, discussion questions, and ways to take action on the issue of whether the U.S. federal government should pay reparations to descendants of enslaved people, go to ProCon.org.

Reparations are payments (monetary and otherwise) given to a group that has suffered harm. For example, Japanese-Americans who were interned in the United States during World War II have received reparations.

Arguments for reparations for slavery date to at least Jan. 12, 1865, when President Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Union General William T. Sherman met with 20 African American ministers in Savannah, Georgia. Stanton and Sherman asked 12 questions, including: “State in what manner you think you can take care of yourselves, and how can you best assist the Government in maintaining your freedom.” Appointed spokesperson, Baptist minister, and former slave Garrison Frazier replied, “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor … and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare … We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.”

On Jan. 16, 1865, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15 that authorized 400,000 acres of coastal land from Charleston, South Carolina to the St. John’s River in Florida to be divided into forty-acre plots and given to newly freed slaves for their exclusive use. The land had been confiscated by the Union from white slaveholders during the Civil War. Because Sherman later gave orders for the Army to lend mules to the freedmen, the phrase “forty acres and a mule” became popular.

However, shortly after Vice President Andrew Johnson became president following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on Apr. 14, 1865, he worked to rescind the order and revert the land back to the white landowners. At the end of the Civil War, the federal government had confiscated 850,000 acres of former Confederates’ land. By mid-1867, all but 75,000 acres had been returned to the Confederate owners.

Other efforts and arguments have been made to institute or deny reparations to descendants of slaves since the 1860s, and the issue remains divisive and hotly debated. An Oct. 2019 Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll found 29% of Americans overall approved of reparations. When separated by race, the poll showed 74% of black Americans, 44% of Hispanics, and 15% of white Americans were in favor of reparations.

President Obama outlined the political difficulty of reparations on his podcast with Bruce Springsteen, “Renegades: Born in the U.S.A.” He said, “So, if you ask me theoretically: ‘Are reparations justified?’ The answer is yes. There’s not much question that the wealth of this country, the power of this country was built in significant part — not exclusively, maybe not even the majority of it — but a large portion of it was built on the backs of slaves. What I saw during my presidency was the politics of white resistance and resentment, the talk of welfare queens and the talk of the undeserving poor and the backlash against affirmative action… all that made the prospect of actually proposing any kind of coherent, meaningful reparations program struck me as, politically, not only a non-starter but potentially counterproductive.”

- Slavery led to giant disparities in wealth that should be addressed with reparations.

- Slavery left African American communities at the mercy of the “slave health deficit,” which should be addressed with reparations.

- There is already precedent for the paying of reparations to the descendants of slaves and to other groups by the US federal government, US state and local governments, and international organizations.

- No one currently living is responsible for righting the wrongs committed by long dead slave owners.

- The idea of reparations is demeaning to African Americans and would further divide the country along race lines.

- Reparations would be too expensive and difficult to implement.

This article was published on January 20, 2022, at Britannica’s ProCon.org, a nonpartisan issue-information source. Go to ProCon.org to learn more.