Antonio Rodriguez/AdobeStock

SPECIAL REPORT: WOMEN’S MENTAL HEALTH

“She would never hurt her baby.” These are words commonly uttered by the partners and family members of women presenting to our facilities with postpartum psychosis (PPP) symptoms. In their reluctance to accept the presence of a mental illness and its related risks, and in their desire to get their loved one out of a psychiatric facility and back home with her baby, partners and family members of patients with PPP often minimize the severity of symptoms they have observed and place themselves at odds with the inpatient psychiatric team seeking to hold and treat the patient. Their reasons for doing so are myriad, but often rooted in a lack of understanding of the course of PPP episodes and the potential for devastating outcomes of not providing treatment.

At Connections Health Solutions psychiatric crisis centers in Arizona, where I serve as medical director, we typically have at least 1 patient with PPP. By contrast, many psychiatrists in the community encounter PPP rarely, or not at all. Despite this, it is vital that we are all prepared to recognize the risk factors and early signs of a developing episode, and to provide education and guidance to patients and their supports.

Given the co-occurrence of massive hormone fluctuations, sleep deprivation, and the acute psychological stress of being wholly responsible for keeping a newborn alive, it is no wonder that the postpartum period is fraught with vulnerability for the development of mood disturbances, anxiety disorders, and psychosis. Findings from some studies have shown that a woman’s risk of hospitalization for psychosis is higher in the first postpartum month than it is at any other time in her life.

Helping expectant mothers and their supports prepare for these possibilities, whether it is as common and relatively benign as the so-called “baby blues” or as rare and potentially life-threatening as PPP, is the first step to improving clinical outcomes. As with most psychiatric disorders, early intervention is key to improving clinical outcomes for PPP, and this becomes more feasible when mental health clinicians, patients, and their supports are familiar with risk factors and early warning signs.

A Brief Summary of the Clinical Aspects of PPP

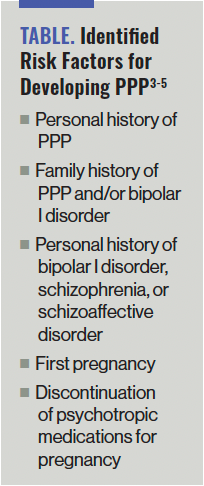

Table. Identified Risk Factors for Developing PPP3-5

PPP is relatively rare, occurring in 1 to 2 per 1000 live births, with at least half of sufferers having no psychiatric history.1,2 Identified risk factors for developing PPP are listed in the Table.3-5 Psychiatrists should take careful family histories when caring for pregnant and postpartum patients, inquiring about any history of psychiatric hospitalization, mania, psychosis, depression, and suicide.

The onset of PPP is rapid and severe, with hallucinations, delusions, emotional distress, and bizarre behaviors seen as early as 2 days after, and typically within 2 weeks of, delivery.2,6 The patients whom I have encountered, presenting with their first episodes of psychosis during the postpartum period, have typically exhibited delusions that are persecutory, religious, and/or grandiose in nature and usually involve the baby (for example, believing that something “evil” is happening to the baby). This differs from patients with a history of psychosis presenting with relapse of symptoms during the postpartum period, who tend to present with psychotic symptoms similar to those exhibited during their previous episodes.

Episodes of PPP can last for months, and subsequent psychotic episodes outside of the postpartum period are common.7 The association between PPP and bipolar I disorder is well established, with onset of psychosis in the immediate postpartum period being a significant predictor of a later diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, although some women do present with an isolated episode of PPP that does not develop into a chronic psychiatric disorder following the postpartum period.6,8,9

There is a significant risk of death by suicide in patients presenting with first-episode PPP, with study data demonstrating rates as high as 4% to 11%, as well as a risk of homicide, with 4% of women with PPP committing infanticide.7,10 PPP should be considered a medical emergency that necessitates rapid identification and intervention, which should always begin by ensuring the safety of the patient and her child(ren). It is recommended that patients with PPP be psychiatrically hospitalized and that they not be left alone with their child(ren) prior to stabilization. With appropriate pharmacotherapy and support, patients can make a full recovery.

Tragic Outcomes of Untreated PPP

Andrea Yates. Kimberlynn Bolanos. Carol Coronado. We are likely all familiar with at least 1 of these names. All 3 women live in infamy after having murdered their children while in the throes of PPP. All 3 also had romantic partners who had observed signs of mental illness in them but were not able to prevent the murder of their children. And of course, all 3 women have faced the vitriol of the US public and criminal justice system.

If you have not viewed the 2019 documentary Not Carol, I suggest you do so. It tells the story of Carol Coronado, a loving and devoted mother who murdered her 3 young children and then stabbed herself in the chest during a PPP episode in 2014. Prosecutors sought the death penalty, but she ultimately received 3 life sentences. The documentary features psychiatrist Torie Sepah, MD, who treated Carol at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in Los Angeles, California, following her arrest and testified in her criminal trial. Sepah speaks and writes passionately about the tragic loss of life that can result from untreated PPP—a tragedy that is too often compounded by a justice system that often seeks to punish rather than to treat these patients, each of whom will suffer until her last breath knowing that her child(ren) died at her hands. But the greatest tragedy of all is that PPP is treatable and these horrific outcomes are preventable when intervention is swift.

Recommendations for Psychiatrists

Arm yourself with knowledge to competently treat the patient. Too often, psychiatrists and other prescribing clinicians unfamiliar with the treatment of psychiatric disorders in pregnant and lactating women err on the side of discontinuing the medications that have kept their patient stable or fail to prescribe appropriate treatment when there is new onset of psychiatric symptoms in this patient population. It is the responsibility of all psychiatrists to become competent in the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders experienced by pregnant and lactating women.

There are numerous high-quality resources available for continuing medical education (CME) for those seeking to enhance their knowledge and competency in perinatal psychiatry. To name a few, Massachusetts General Hospital offers perinatal psychiatry CME modules that can be accessed on their Psychiatry Academy website, and Postpartum Support International offers online trainings and an annual conference, and is responsible for the Perinatal Psychiatric Consult Line. This is a free service staffed by volunteer reproductive psychiatrists who provide guidance to medical professionals with questions about the psychiatric care of pregnant and postpartum patients.

For quick references on medication management of psychiatric disorders in this population, I recommend downloading the InfantRisk app and maintaining a subscription to Reprotox, where you can review extensive summaries of the effects of medications during pregnancy and lactation.

Educate expectant mothers and their supports on the prevalence, signs, and symptoms of perinatal psychiatric disorders. Talk to them about ways to reduce the likelihood of developing severe symptoms. Instruct them on when to reach out and how to do so. Familiarize yourself with your local mental health crisis system and how it can be accessed, then share this knowledge with your patients and their supports.

Ensure timely and frequent follow-up for your patients who have recently given birth, particularly for patients with a history of bipolar disorder, depression, and/or psychosis, and those with notable family histories. Offer telepsychiatry options for women who do not have a support person to watch their baby or who may be too tired to safely get behind the wheel of a vehicle.

Contribute to public discourse on the topic of PPP. Promote an understanding of PPP and reduce stigma by writing articles for mainstream media and participating in discussions on social media that can be accessed by the lay public.

Concluding Thoughts

PPP is a serious psychiatric disorder with a significant risk of morbidity and mortality for the patient and her child(ren). Early and aggressive treatment is vital to improving outcomes, and we must find ways to reduce the barriers to achieving them. This starts with psychiatrists gaining expertise on PPP and sharing that knowledge with others.

When it comes to the woman experiencing PPP, it may be true that she would never hurt her baby, but she is not herself. Fortunately, there is treatment and there is hope.

Dr Costales serves as Arizona medical director at Connections Health Solutions, overseeing all clinical operations for Connections crisis response centers in Phoenix and Tucson. Prior to joining Connections, she spent time working with individuals designated as being seriously mentally ill in outpatient settings.

References

1. Terp IM, Mortensen PB. Post-partum psychoses: clinical diagnoses and relative risk of admission after parturition. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:521-526.

2. Blackmore ER, Rubinow DR, O’Connor TG, et al. Reproductive outcomes and risk of subsequent illness in women diagnosed with postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(4):394-404.

3. Videbech P, Gouliaev G. First admission with puerperal psychosis: 7-14 years of follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(3):167-173.

4. Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Postpartum mood disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 2):34-40.

5. Jones I, Craddock N. Familiality of the puerperal trigger in bipolar disorder: results of a family study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):913-917.

6. Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, Howard LM. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1789-1799.

7. Gilden J, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Long-term outcomes of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19r12906.

8. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Psychiatric disorders with postpartum onset: possible early manifestations of bipolar affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):428-434.

9. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

10. Parry BL. Postpartum psychiatric syndromes. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 6th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1995.