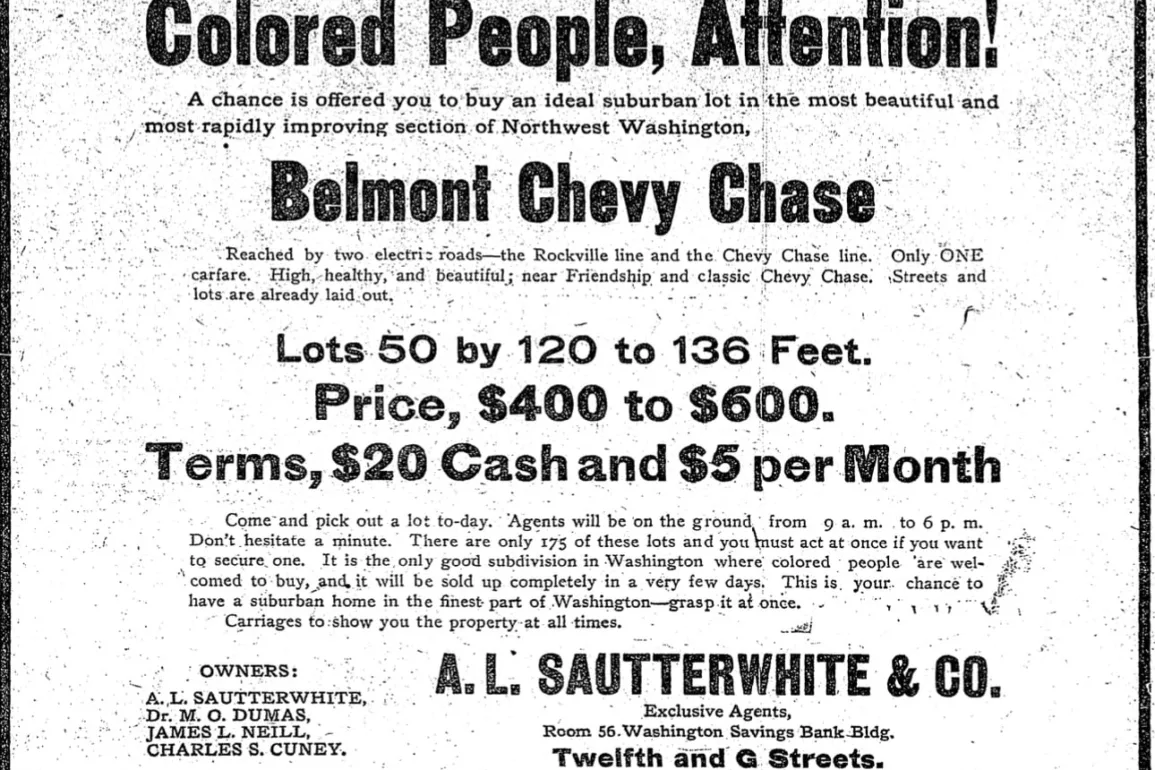

Some members of Washington’s White power structure must have spit out their coffee when they saw the display ad in The Washington Post’s real estate section on the morning of July 1, 1906.

“Colored People, Attention!” blared the headline. “A chance is offered you to buy an ideal suburban lot in the most beautiful and most rapidly improving section of Northwest Washington.”

This new neighborhood — “the only good subdivision in Washington where colored people are welcomed to buy,” the ad announced — would include fine homes on large lots. It would be called “Belmont.”

It turned out that African Americans weren’t exactly welcomed to buy. There is no Belmont. The reasons will be explored at Saturday’s Montgomery County History Conference. It’s just one of the sessions on tap from 9 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. on the Rockville campus of Montgomery College (registration and coffee, 8 to 9 a.m.).

Michel Dumas, Alexander Sautterwhite, Charles Cuney and James Neill were the Black business executives who planned to build a high-end suburb for Black people in Chevy Chase. They had used a White “straw” buyer to pull together a 31-acre parcel of land abutting Wisconsin Avenue, just over the District line in Montgomery County.

“Of course, the neighbors started to notice,” said Kim Bender, who is presenting the session with Neil Flanagan. “There was a lot of threatening behavior, especially from Somerset.”

The Chevy Chase Land Co., founded by the racist Francis G. Newlands, still controlled the complicated nest of mortgages connected to Belmont. The four Black developers found themselves mired in litigation that stretched for years, denying them the opportunity to build.

“I think if it had been White people doing the same thing, Chevy Chase Land Co. and their other business partners would have released the title to the lots,” Bender said. “They refused to accept payment from the Belmont syndicate.”

For decades there has been the belief that the planned neighborhood was intended for Black servants serving wealthy Chevy Chase residents. In fact, it was the opposite: a place for wealthy African Americans.

Flanagan pored through court records at the Maryland State Archives to chase down a story that he said “has been hidden in plain sight.”

If Chevy Chase has always been a place for people with a lot of money, the Montgomery County Poor Farm and Almshouse was for people with no money at all.

“These were the poorest of the poor,” said Julianne Mangin, who is presenting a session on the almshouse with Katherine Rogers.

The almshouse property would have covered a 200-acre area at the intersection of today’s Interstate 270 and Wootton Parkway. A farm was intended to provide for residents, who, besides the poor, also included mentally ill and disabled people. The housing was segregated, with paltrier facilities for Black residents.

“It was the place of last resort,” Mangin said. “In the entire existence of the almshouse, none of the overseers had any experience with social work or health care. They were picked because they had good reputations as farmers and had political connections.”

The land was used as a paupers’ field, too. Mangin confirmed that nearly 200 people were buried on the poor farm.

“There were close to 100 bodies that were located during various construction projects and reburied at Parklawn Cemetery in Rockville,” said Mangin. Some believe the rest are buried under I-270.

The almshouse was closed in 1948. The Montgomery County Detention Center is on the site today.

It’s probably a stretch to call Rebecca G. Fields the Katharine Graham of turn-of-the-century Montgomery County. But it wouldn’t be exactly wrong, either. She owned the Montgomery County Sentinel, the paper of record in the county seat. She took it over after her husband, Matthew, died in 1871.

“Not only did she take it over and run it, she ran it for almost 60 years,” said Sarah Hedlund, who is presenting a session on Fields at the conference.

“The narrative is that she was trying to keep it secret that she was in charge,” fearful a woman owner would drive business away, said Hedlund. But Rockville was a small town and it must have been common knowledge.

Still, Fields didn’t leave many traces: no diaries or letters. It’s hard to discern her editorial viewpoints, Hedlund said. We do know she didn’t like new technology. The paper used a hand-cranked press. It didn’t have a phone until 1930. Fields hated photography and riding in trains, Hedlund said.

At age 98, Fields told an interviewer that she didn’t want her picture taken, saying, “I never allowed my picture to be taken when I was young and good looking and I’m certainly not going to have it taken now.”

Rebecca Fields died two years later at age 100.

To register for the history conference — $65; $15 for students — visit montgomeryhistory.org.