Key Points

Question

Is perceived interpersonal racism associated with stroke risk?

Findings

In this cohort study of 48 375 US Black women, those who reported experiencing interpersonal racism in situations involving employment, housing, and the police had an estimated 38% increased risk of stroke compared with women who reported no such experiences.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the high burden of racism experienced by Black US women may contribute to racial disparities in stroke incidence.

Importance

Black individuals in the US experience stroke and stroke-related mortality at younger ages and more frequently than other racial groups. Studies examining the prospective association of interpersonal racism with stroke are lacking.

Objective

To examine the association of perceived interpersonal racism with incident stroke among US Black women.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Black Women’s Health Study, a prospective cohort study of 59 000 Black women from across the US, assessed the longitudinal association between perceived interpersonal racism and stroke incidence. Stroke-free participants were followed up from 1997 until onset of stroke, death, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2019). Cox models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs, adjusting for major confounders, including education, neighborhood socioeconomic environment, and cardiometabolic factors. Data analysis was performed from March 2021 until December 2022.

Exposure

On a questionnaire completed in 1997, participants reported experiences of racism in everyday life and when dealing with situations that involved employment, housing, and interactions with police.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Strokes were identified through self-report on biennial questionnaires, medical records adjudication, and linkage with the National Death Index.

Results

In 1997, 48 375 Black women (mean [SD] age, 41 [10] years) provided information on perceived interpersonal racism and were free of cardiovascular disease and cancer. During the 22 years of follow-up, 1664 incident stroke cases were identified; among them, 550 were definite cases confirmed by neurologist review and/or National Death Index linkage. Multivariable HRs for reported experiences of racism in all 3 domains of employment, housing, and interactions with police vs no such experiences were 1.38 (95% CI, 1.14-1.67), a 38% increase, for all incident cases and 1.37 (95% CI, 1.00-1.88) for definite cases. For comparisons of women in the highest quartile of everyday interpersonal racism score vs women in the lowest quartile, multivariable HRs were 1.14 (95% CI, 0.97-1.35) for analyses that included all incident stroke and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.83-1.45) for analyses that included definite cases only.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, Black women who reported experiences of interpersonal racism in situations involving employment, housing, and interactions with police appeared to have an increased risk of stroke, even after accounting for demographic and vascular risk factors, suggesting that the high burden of racism experienced by Black US women may contribute to racial disparities in stroke incidence.

Introduction

Black US individuals are especially vulnerable to stroke, with a 2- to 3-fold higher stroke incidence1–4 and 1.2-fold higher stroke mortality than White US individuals.5 Black women, in particular, experience stroke and stroke-related mortality at higher rates and earlier onset than women in any other racial group.6,7

Racism in the US (both interpersonal racism and structural racism) disproportionally affects Black individuals. Racism is a complex construct and exists in multiple forms and at multiple levels.8–11 Direct evidence linking racism with incident stroke is quite limited. The Reasons for Geographic and Regional Differences in Stroke study12 provided important evidence that risk of stroke increased with increasing numbers of adverse social determinants of health, but racism was not directly assessed. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis13 reported no association of race-based discrimination with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD), but the association specifically with stroke was not reported. Some studies14–16 have reported subclinical CVD associated with discrimination, although the results were inconsistent. The Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS), begun in 1995, asked a series of validated questions on experiences of racism in 1997, allowing for a prospective examination of the association of perceived interpersonal racism with incident stroke among Black women for 22 years of follow-up.

The Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board approved this cohort study. Study participants provided written informed consent. This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for observational studies.

Study Population

The BWHS17 is an ongoing, prospective cohort study that initially enrolled 59 000 participants through Essence Magazine and Black professional organizations (94% of the BWHS participants came from the Essence Magazine subscription lists). The BWHS is the largest contemporary cohort of Black women in the US, and most Black women were from 17 states across the mainland US, including California, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin, and Washington, District of Columbia. BWHS participants live in neighborhoods with a wide range of neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES). Black women aged 21 to 69 years (median age at baseline, 38 years) enrolled in 1995 by completing health questionnaires. In the initial questionnaire, respondents provided data on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, medical conditions, and lifestyle factors. All but 5% of BWHS participants were born in the US.17 Every 2 years, participants update health information on follow-up mailed and web health questionnaires. Follow-up through 2019 is complete for 86.2% of person-years.

Incident Stroke

Stroke cases were ascertained through (1) biennial BWHS questionnaires, which asked participants to report whether a physician had given them a diagnosis of stroke and the year of the diagnosis; (2) stroke medical records, which were reviewed and by a committee of neurologists (H.J.A., V.-A.L., and J.G.S.); and (3) the National Death Index (NDI).18 On the 1995 BWHS questionnaire, participants were asked, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following conditions” (yes or no), and among the list was stroke. If yes, participants were asked to mark the age at which stroke was first diagnosed (<30>19: a new focal (or at times global) neurological impairment of sudden onset and of presumed vascular origin.19 These included ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. In addition, retinal and spinal cord infarction were included in this definition. Events not meeting this definition but with clinical evidence consistent with stroke, including (1) stroke that had been aborted by thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy and (2) symptoms lasting less than 24 hours with visible infarction on neuroimaging (ie, transient ischemic attack with demonstration of an ischemic lesion on magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging), were also classified as stroke events. A reviewer with uncertainty about the status of the event forwarded it to a second reviewer. A joint discussion then took place between 2 to 3 reviewers to achieve a consensus (H.J.A., V.-A.L., or J.G.S.). Uncertainty was resolved through committee meetings for adjudication.

Appropriate medical records were obtained for 618 of 1976 participants who reported stroke. Among them, 450 (73%) were confirmed through adjudication and 168 were disconfirmed. Interrater reliability between the independent reviewers for adjudication of a confirmed stroke event was excellent (κ = 92%). Fatal stroke was ascertained through linkage with the NDI (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes I60-I69).

For the present analysis, the primary end point includes stroke confirmed by medical records review or NDI linkage, or self-reported stroke cases for which medical records could not be obtained. Stroke confirmed by medical records review or NDI were considered as definite cases. The secondary end point was restricted to definite cases only.

Perceived Interpersonal Racism

BWHS questions on racism and/or discrimination were adapted from an instrument developed by Williams et al,20 designed to measure perceived interpersonal racism. We assessed perceived interpersonal racism experienced by the individual in everyday life and perceived interpersonal racism when dealing with situations that involved employers, housing, and police (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).21–23 The present analysis is based on 1997 responses to the perceived interpersonal racism questions,20,24 which represent perceived racism at midlife for most of the participants.

Five questions addressed interpersonal racism in everyday activities, such as, “People act as if they think you are dishonest,” with 5 responses ranging from never (scored as 0) to almost every day (scored as 4). The score for interpersonal racism in everyday life was the mean of responses to all 5 questions (possible scores, 0-4) and was categorized into quartiles. Three other questions asked whether the respondent had ever experienced discrimination owing to her race in employment, housing, and the police.21–25 The score for perceived racism in institutional settings was the sum of positive responses to the 3 questions about employment, housing, and police (possible scores, 0, 1, 2, and 3). The BWHS has previously reported associations of perceived interpersonal racism with increased risks of type 2 diabetes26 and obesity,22 decreased subjective cognitive function,23 and other outcomes.21,24,27–34

Covariate Assessment

Covariates were chosen a priori on the basis of factors known to be associated with increased risk of stroke. We included age (continuous), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; ≤24.9, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, and ≥35), education level (≤12, 13-15, 16, and ≥17 years), neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) in quintiles,35 vigorous physical activity (<1>

Hypertension, reported by participants on biennial questionnaires, was defined as physician-diagnosed hypertension together with use of an antihypertensive medication or diuretic, or use of an antihypertensive alone. In a prior validation study,36 138 of 139 self-reports of hypertension (99%) were confirmed by medical records. Women who reported a diagnosis of diabetes occurring at age 30 years or older were considered to have type 2 diabetes. In a validation study,37 217 of 229 women (94%) who reported diabetes were confirmed by their physicians to have type 2 diabetes.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. For each study participant, follow-up was from 1997 until the onset of incident stroke, death, loss to follow-up, or the end of study follow-up (December 31, 2019), whichever came first. On the basis of known risk factors for stroke, we decided a priori to examine potential effect modification by baseline covariates, including age, residence in the so-called Stroke Belt (ie, Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee),38 educational level, and neighborhood SES. We used the Wald test to assess the significance of interaction. We also derived Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each of racism categories in the primary analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). All analyses involved 2-sided tests with a significance level of P < .05. Data analysis was performed from March 2021 until December 2022.

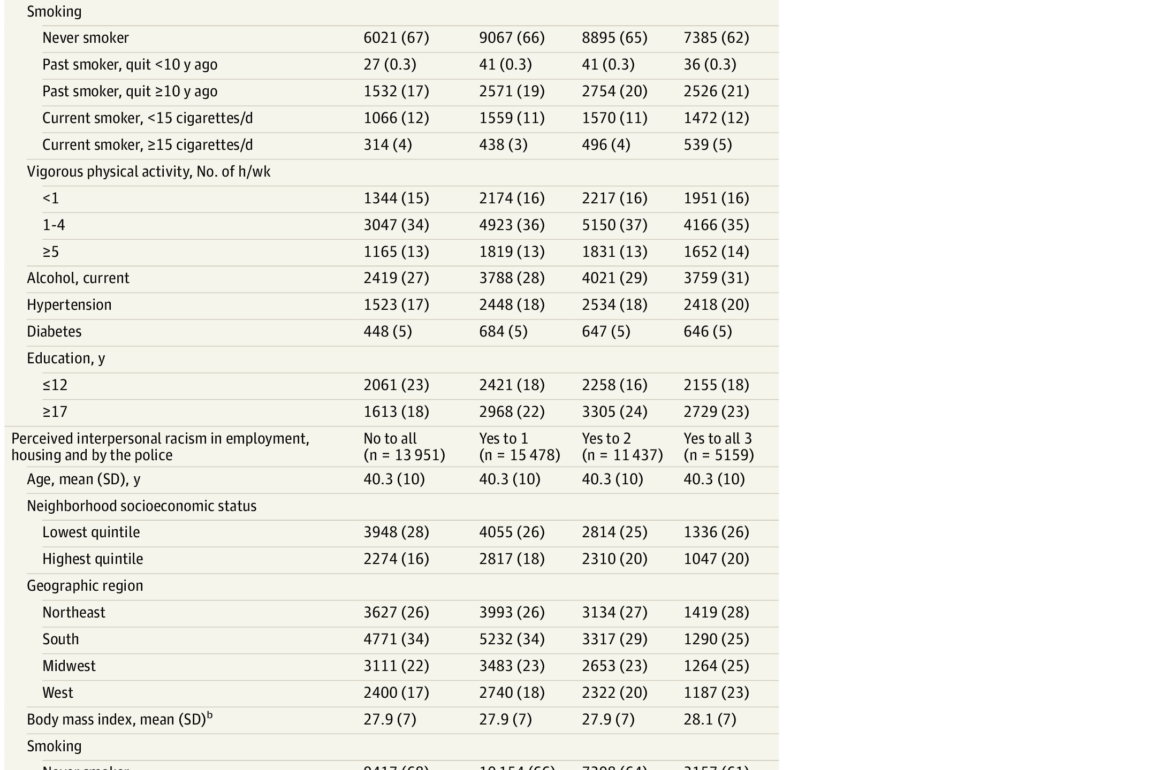

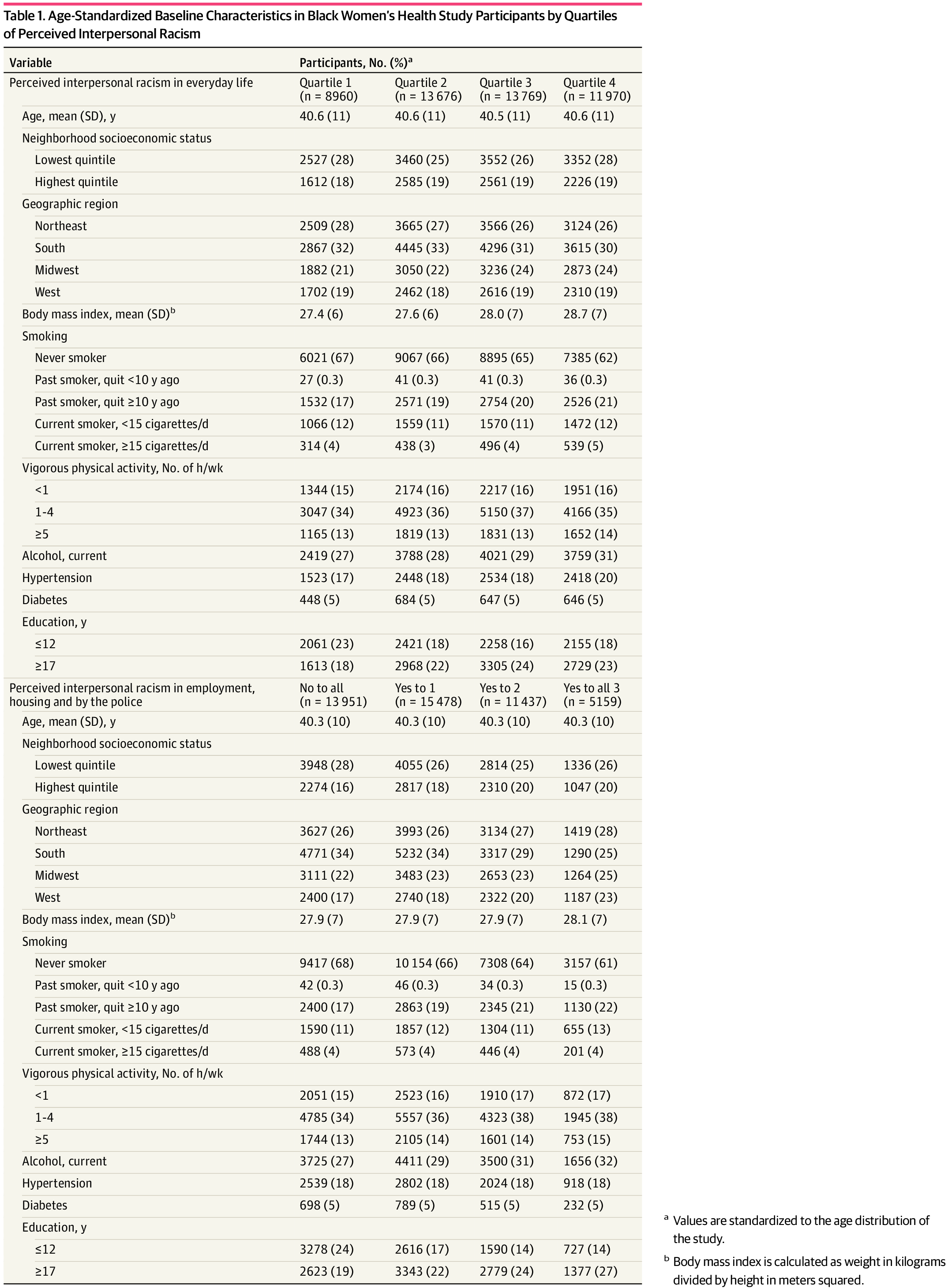

In 1997, 48 375 women (mean [SD] age, 41 [10] years) provided information on perceived interpersonal racism and were free of CVD (843 participants) and cancer (1615 participants). Compared with women in the lowest quartile of perceived interpersonal racism score, those in the highest quartile were similar with respect to neighborhood SES, body mass index, smoking, and physical activity (Table 1). They were more likely to have a higher educational level. A total of 27 155 women (59%) perceived racism in employment, 16 109 (35%) perceived racism in housing, and 11 046 (24%) perceived racism in interactions with police. In the present study, 5159 participants (11%) reported yes to all 3 questions on perceived racism in employment, housing, and interactions with police, and 13 951 women (30%) reported no to all 3 questions. In this study, the correlation coefficient between everyday racism and housing, employment, and police scores was 0.36. Women who reported racism in employment, housing, and the police were more likely to live in high SES neighborhoods, less likely to live in the South, and more likely to have a higher educational level than those who reported no such experience (Table 1).

During follow-up from 1997 through 2019, a total of 1664 incident strokes were identified. As shown in Table 2 and eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1, the age-adjusted HR for stroke was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.09-1.50; P for trend < .001) for women in the highest quartile of perceived interpersonal racism in everyday life vs those in the lowest quartile. The multivariable HR was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.97-1.35; P for trend = .03). When comparing women who experienced racism in employment, housing, and the police with those with no such experience, the age-adjusted HR for stroke was 1.42 (95% CI, 1.18-1.70; P for trend < .001). The multivariable HR was 1.38 (95% CI, 1.14-1.67; P for trend < .001), or a 38% increase, for women who answered yes to all 3 domains (employment, housing, and police) vs women who answered no to all 3 domains.

We repeated the analyses restricted to 550 definite cases that were confirmed through neurologist adjudication and/or the NDI (Table 3). For perceived interpersonal racism in everyday life, there was no association with risk of stroke (multivariable adjusted HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.83-1.45; P for trend = .66). For women who reported interpersonal racism in all 3 of the domains of employment, housing, and police compared with none of the domains, the multivariable adjusted HR was 1.37 (95% CI, 1.00-1.88; P for trend = .05) (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis that restricted definite strokes to only those with medical records adjudicated by study neurologists, the comparable HR was 1.61 (95% CI, 1.09-2.37) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Across strata of various subgroups, perceived interpersonal racism in employment, housing, and the police was consistently associated with elevated stroke risk (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). For perceived interpersonal racism in everyday life, the HR was most increased among participants in the lowest quartile of neighborhood SES (P for interaction = .001) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this large, prospective cohort study of 48 375 Black women, we found that participants who reported experiencing interpersonal racism in 3 institutional settings had an estimated 38% increased risk of stroke compared with women who reported no such experiences. The elevated stroke risk was present in analyses of all incident strokes, as well as in analyses restricting to definite strokes. For perceived interpersonal racism in everyday life, stroke risk was elevated in an analysis that included all stroke cases, but there was no evidence of an increased risk of stroke based on analyses of the smaller number of definite cases.

Disproportionate numbers of Black US individuals face multiple adverse experiences over the life course, including racism and poverty; these are recognized as social determinants of health.39,40 Racism may act as a psychosocial stressor and thereby elevate systemic inflammation, impair endothelial function, and dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.41–43 Previous studies have linked perceived interpersonal racism with worse mental health outcomes,41 higher risk of hypertension,24,44–48 increased systolic blood pressure,48 unhealthy behavior and lifestyles,49,50 higher allostatic load,51–53 higher inflammatory markers,54 hormone dysregulation,55,56 and shorter telomere length.27,57 Although several large prospective cohort studies have investigated stroke risk factors among Black US individuals, direct evidence about perceived racism and incident stroke is very limited. The Jackson Heart Study14 reported higher risk of subclinical CVD associated with discrimination, but did not examine stroke end points. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis13reported no association of racial discrimination with risk of all CVD, but associations with stroke were not reported. Our study provides direct evidence on perceived racial discrimination at the interpersonal level in relation to subsequent occurrence of incident stroke.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the prospective cohort design with a large sample of Black women, wide geographic distribution, long duration of follow-up from 1997 until 2019, large number of incident strokes, and detailed information on potential confounding factors. Our study also has some limitations. First, the concept of racism is complex, and racism exists in multiple forms and at multiple levels. Structural racism58 (ie, the ways societies reinforce racial differences in access to housing, education, employment, health care, and criminal justice) may also affect stroke risk and is not captured by questions about interpersonal racism. Second, our primary stroke end point included self-reported stroke. BWHS participants responded to the question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have stroke?” Medical records were not available for all stroke events, either because the participant declined to sign a medical records release or because the appropriate hospital was not identified or did not have the records. A team of vascular neurologists performed a careful review of records that were obtained. The confirmation rate of 73% is similar to that reported in other studies of stroke.59 Prior studies have shown that the question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have stroke?” has good sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients in the community with a diagnosis of stroke.59,60

Third, perceived racism captures an individual’s perceptions of an experience of racism and relies on a participant’s self-report. Perceived racism is inevitably subject to measurement error. An individual who experiences racism may overreport or underreport these sensitive events or change their interpretations and perceptions of these experiences over time. Because self-reported information on stroke was collected prospectively by biennial questionnaire, it is highly unlikely that stroke events were reported differentially with respect to the perceived interpersonal racism level reported in 1997. However, it is possible that BWHS participants who survived a stroke with severe deficits may have been less likely to respond.

Fourth, despite our efforts to control for confounders and risk factors for stroke, our study is observational and may still have been subject to unmeasured and residual confounding. For example, in our study, we were unable to adjust for history of atrial fibrillation, a risk factor for stroke. However, given the extensive list we included for major confounder adjustment, it is highly unlikely that our study will have such a strong unmeasured confounder.

Fifth, our study consisted of Black women with high educational levels compared with the general population of Black women. Participants in the BWHS needed to have sufficient literacy to complete health questionnaires every 2 years. BWHS participants represent the educational levels of Black US women, with underrepresentation of women with the lowest level of education (ie, <12 years>

Conclusions

In this investigation of perceived interpersonal racism in relation to incident stroke, experiences of interpersonal racism in everyday life were associated with higher risk of incident stroke, although there was no association for the smaller group of definite strokes. However, in both analyses, individuals who reported experiencing interpersonal racism in situations concerning housing, employment, and the police appeared to have an increased risk, estimated to be 38%, compared with women who reported no such experiences. It is possible that the high burden of racism experienced by Black US individuals may contribute to racial disparities in stroke incidence.

Accepted for Publication: October 4, 2023.

Published: November 10, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.43203

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2023 Sheehy S et al. JAMA Network Open.

Concept and design: Sheehy, Cozier, Rosenberg.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Sheehy.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Sheehy.

Obtained funding: Sheehy, Palmer.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Sheehy, Cozier.

Supervision: Sheehy, Aparicio, Palmer, Rosenberg.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Lioutas reported receiving personal fees from Qmetis and grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01CA058420, UM1CA164974, U01CA164974, L30 NS093634, and R01MD015085). Dr Aparicio is supported by an American Academy of Neurology Career Development Award and by Boston University’s Aram V. Chobanian Assistant Professorship.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2.

Additional Contributions: We thank the staff and participants in the Black Women’s Health Study.

References

MR, Pu

J, Howard

G,

et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Stroke Council. Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

B, Goldstein

LB, Higashida

RT,

et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee and Stroke Council. Forecasting the future of stroke in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2361-2375. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e31829734f2PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

C, McCullough

LD, Awad

IA,

et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545-1588. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

WD, Folsom

AR, Chambless

LE,

et al. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults: 9-year follow-up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30(4):736-743. doi:10.1161/01.STR.30.4.736PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

A, Benson

RT, Tagge

R, Moy

CS, Wright

CB, Ovbiagele

B. Inaugural health equity and actionable disparities in stroke: understanding and problem-solving symposium. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3382-3391. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030423PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

LE, Sharrief

A, Gardener

H, Jenkins

C, Boden-Albala

B. Considerations in addressing social determinants of health to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in stroke outcomes in the United States. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3433-3439. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030426PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

K, Elkind

MSV, Benjamin

RM,

et al; American Heart Association. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities—a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454-e468. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SA, Lutsey

PL, Roetker

NS,

et al. Perceived discrimination and incident cardiovascular events: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(3):225-234. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv035PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

R, Cardarelli

KM, Fulda

KG,

et al. Self-reported racial discrimination, response to unfair treatment, and coronary calcification in asymptomatic adults: the North Texas Healthy Heart study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:285. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-285PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

L, Adams-Campbell

L, Palmer

JR. The Black Women’s Health Study: a follow-up study for causes and preventions of illness. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1995;50(2):56-58.PubMedGoogle Scholar

AE, Robins

M, Weinfeld

FD. The National Survey of Stroke: clinical findings. Stroke. 1981;12(2 pt 2)(suppl 1):I13-I44.PubMedGoogle Scholar

YC, Yu

J, Coogan

PF, Bethea

TN, Rosenberg

L, Palmer

JR. Racism, segregation, and risk of obesity in the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(7):875-883. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu004PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

P, Schon

K, Li

S, Cozier

Y, Bethea

T, Rosenberg

L. Experiences of racism and subjective cognitive function in African American women. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12067. doi:10.1002/dad2.12067PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

YC, Palmer

JR, Horton

NJ, Fredman

L, Wise

LA, Rosenberg

L. Relation between neighborhood median housing value and hypertension risk among black women in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):718-724. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.074740PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

KL, Stuver

SO, Cozier

YC, Palmer

JR, Rosenberg

L, Ruiz-Narváez

EA. Perceived racism and incident diabetes in the Black Women’s Health Study. Diabetologia. 2017;60(11):2221-2225. doi:10.1007/s00125-017-4400-6PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

TN, Zhou

ES, Schernhammer

ES, Castro-Webb

N, Cozier

YC, Rosenberg

L. Perceived racial discrimination and risk of insomnia among middle-aged and elderly Black women. Sleep. 2020;43(1):zsz208. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsz208PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CP, Carter-Nolan

PL, Makambi

KH,

et al. Impact of perceived racial discrimination on health screening in black women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):287-300. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0273PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

TR, Williams

CD, Makambi

KH,

et al. Racial discrimination and breast cancer incidence in US Black women: the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(1):46-54. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm056PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

TN, Palmer

JR, Rosenberg

L, Cozier

YC. Neighborhood socioeconomic status in relation to all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in the Black Women’s Health Study. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(2):157-164. doi:10.18865/ed.26.2.157PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

AV, Bakris

GL, Black

HR,

et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JR, Boggs

DA, Krishnan

S, Hu

FB, Singer

M, Rosenberg

L. Sugar-sweetened beverages and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1487-1492. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.14.1487PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SK, Liu

Y, Quarells

RC, Din-Dzietharn

R; Metro Atlanta Heart Disease Study Group. Stress-related racial discrimination and hypertension likelihood in a population-based sample of African Americans: the Metro Atlanta Heart Disease Study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4):585-593.PubMedGoogle Scholar

M, Diez-Roux

AV, Dudley

A,

et al. Perceived discrimination and hypertension among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):S258-S265. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300523PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CB, Vines

AI, Kaufman

JS, James

SA. Cross-sectional association between perceived discrimination and hypertension in African-American men and women: the Pitt County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(5):624-632. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm334PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CM, McGrath

JJ, Herzig

AJM, Miller

SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):20-34. doi:10.1037/a0033718PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JA, Osborn

CY, Mendenhall

EA, Budris

LM, Belay

S, Tennen

HA. Beliefs about racism and health among African American women with diabetes: a qualitative study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(3):224-232. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30298-4PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

TT, Aiello

AE, Leurgans

S, Kelly

J, Barnes

LL. Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(3):438-443. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.011PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

ES, Sheu

YT, Butler

C, Cornelious

K. Relationships between perceived stress, coping behavior and cortisol secretion in women with high and low levels of internalized racism. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(2):206-212.PubMedGoogle Scholar

T, Wegner

R, Pierce

J, Lumley

MA, Laurent

HK, Granger

DA. Perceived discrimination, racial identity, and multisystem stress response to social evaluative threat among African American men and women. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(3):293-305. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000406PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

K, Hense

HW, Rothdach

A, Weltermann

B, Keil

U. A single question about prior stroke versus a stroke questionnaire to assess stroke prevalence in populations. Neuroepidemiology. 2000;19(5):245-257. doi:10.1159/000026262PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref