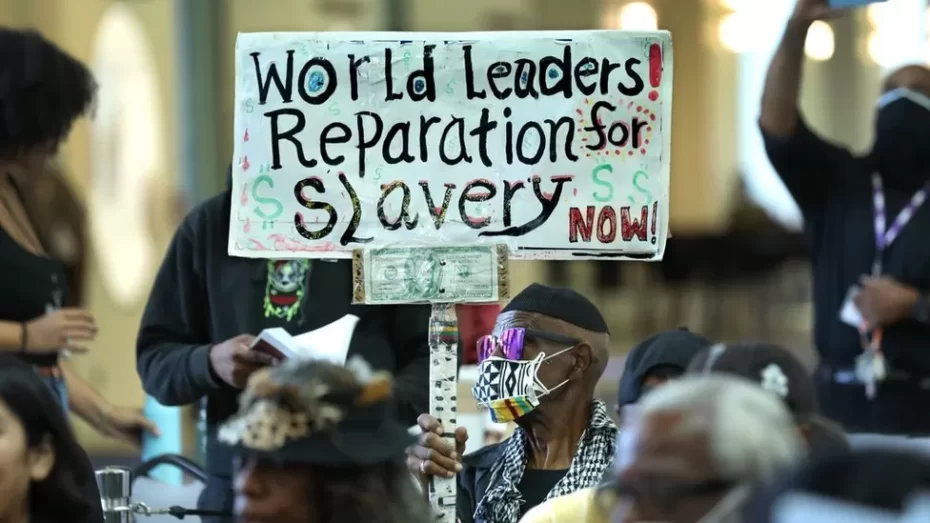

The movement is unstoppable. In the same week, King Charles expresses regrets for the British colonial violence committed in Kenya, and German President Steinmeier apologises to Tanzania for the atrocities committed by Germans. The question is burning: will European countries now be forced to allocate a portion of their taxpayers’ funds to substantially compensate the descendants of slaves?

The cause is ardently defended from the Caribbean, which finds itself at the forefront of this fight, led primarily (but not exclusively) by Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who calls for this debate to take place among “equal partners.” The Caribbean nations are not seeking charity from former colonizers. Instead, they have developed a 10-point plan for reparations or compensations, ranging from formal and complete apologies to be issued by certain European nations to the provision of funds primarily for healthcare, education, and access to the latest technologies for the formerly colonised peoples. The challenge faced by these African, Asian, and Caribbean countries demanding recognition – not just symbolic – of the ravages perpetrated by the colonizers is even more colossal considering the staggering sums involved.

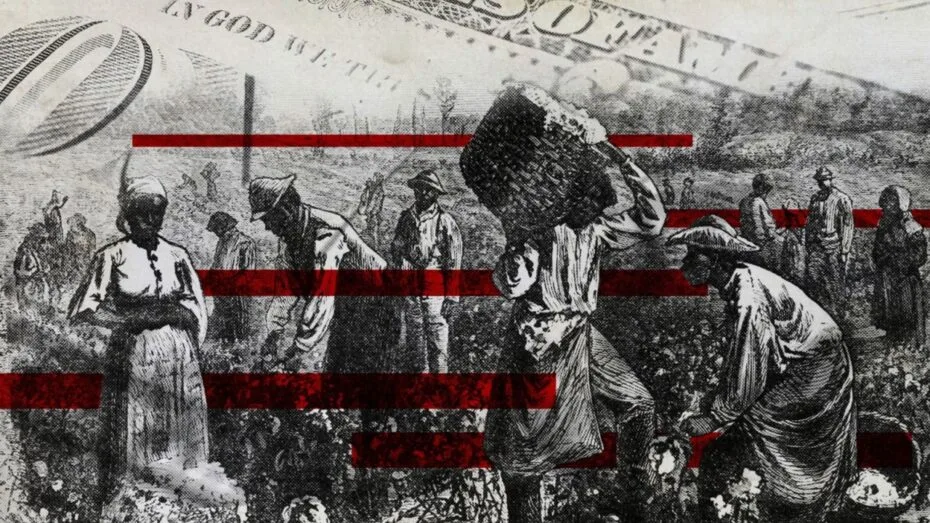

An American expert panel has estimated the consequences of slavery to be at least 130 trillion dollars: a sum that would bankrupt many of the countries affected by the reparations settlement, calculated proportionally based on the duration of their occupation and exploitation of these territories. In other words, some requesting countries have few illusions about the final amounts that will one day be redistributed to them. However, it is the determination and voices from the Caribbean that are now raising the stakes, arguing that no fewer than 5.5 million Africans were forcibly brought to these regions, a number ten times higher than the number of blacks sent to North America.

Apart from apologies from some heads of state, most European countries respond with polite silence. This palpable discomfort is evidently indicative of the fundamental ambiguity in which some, like France, find themselves. While slavery is recognized as a crime against humanity, the French Court of Cassation nonetheless rejects (as it did last July) an appeal filed by Martinican descendants of slaves claiming damages from the state… for what is indisputably a crime duly recognized by law.

Could part of the solution be for these compensations to come from the private sector? The example to follow might be the British one, where a few families, as famous as they are respected, whose fortunes are extraordinarily indebted to slavery, have taken the initiative under pressure from parliamentarians who are descendants of slaves. Indeed, within some illustrious families in the UK, which, along with France, was a major colonial power, there is a groundswell emerging, gradually pulling in former, less affluent slave owners, who are working together to establish a comprehensive system that includes a refreshing element of transparency. Under the impetus of the Gladstone family, more and more of these former masters are digitising their family trees to help and contribute to a better understanding of the history of the families of former slaves.

The debate continues, and we can only welcome it, in the interest of all, for the peace of all. It is high time that this issue becomes a priority on diplomatic agendas.

For more on the author, Michel Santi, visit his website here: michelsanti.fr

For the latest in LUXUO business reads, click here.