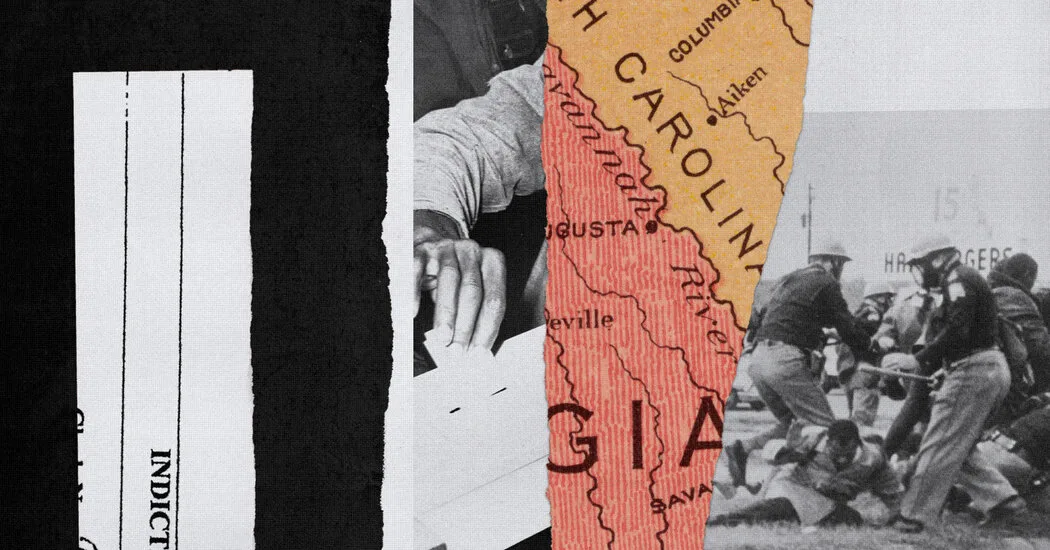

With her sweeping indictment of former President Donald Trump and over a dozen co-conspirators, the Fulton County, Ga., district attorney Fani Willis is now set to prosecute her case in a court of law. Just as important, it is essential that she and others continue to explain to the American public why the decision serves a critical purpose beyond the courts and for the health of our constitutional order.

The indictment should be situated in the broader arc of American political development, particularly in the South. That history justifies using the criminal justice system to protect the democratic process in Georgia — a critical swing state — for elections now and in the future.

We have the benefit of hindsight to heed the great lesson of the Reconstruction era and the period of redemption that followed: When authoritarians attack democracy and lawbreakers are allowed to walk away from those attacks with impunity, they will try again, believing there are no repercussions.

We should not make those mistakes again.

The period after the American Civil War entrenched many of America’s political ills. Ex-confederates were welcomed back into the body politic without meaningful penance. There were vanishingly few arrests, trials and lengthy punishments. Suffering minimal political disabilities, they could muster enough power to “redeem” Southern governments from biracial coalitions that had considerable sway to remake the South.

Examples of democratic decay were regrettably abundant. An early sign occurred in Louisiana. With a multiracial electorate, Reconstruction Louisiana held great promise. During contentious state elections in 1872, Louisiana Democrats intimidated Black voters from casting ballots and corruptly claimed victory. The disputed election spurred political violence to assert white supremacy, including the Colfax Massacre in 1873, where as many as 150 Black citizens were killed in Grant Parish when a white mob sought to take control of the local government.

Federal prosecutors brought charges against a number of the perpetrators. But in 1876, the Supreme Court held in United States v. Cruikshank that the federal government could not prosecute private violence under the 14th Amendment because it could only protect citizens against constitutional rights violations by state actors. By its decision, the court gave license to mobs to disrupt the peaceful transition of power with grave consequences.

South Carolina could have been a Reconstruction success story. Its state constitution and government reflected the values and priorities of its Black majority. The planter elite attacked the Reconstruction government as a socialist rabble and baselessly mocked elected officials as incompetent. In the lead-up to elections in 1876, political violence brewed across the state, and Democrats secured a narrow victory. But democratic decay was precipitous. Over time, South Carolina imposed new limits on voting, moving precincts into white neighborhoods and creating a confusing system. Legislators passed the Eight Box Law, which required voters to submit a separate ballot for each elected office in a different box and invalidated any votes submitted in the wrong box. This created a barrier to voting for people who could not read.

The lack of repercussions for political violence and voter suppression did little to curb the impulse to crush biracial democracy by mob rule. The backsliding spread like cancer to Mississippi, Virginia and North Carolina.

In Georgia, just before the state was initially readmitted to the Union, Georgians elected a Republican to the governorship and a Republican majority to the state senate. Yet the promise of a strong Republican showing was a mirage. Conservative Republicans and Democrats joined forces to expel more than two dozen Black legislators from the Georgia General Assembly in September 1868. From there, tensions only grew. Political violence erupted throughout the state as elections drew closer that fall, most tragically in Camilla, where white supremacists killed about a dozen Black Georgians at a Republican political rally.

The democratic failures of that era shared three common attributes. The political process was neither free nor fair, as citizens were prevented from voting and lawful votes were discounted. The Southern Redeemers refused to recognize their opponents as legitimate electoral players. And conservatives abandoned the rule of law, engaging in intimidation and political violence to extinguish the power of multiracial political coalitions.

At bottom, the theory behind the Fulton County indictment accuses Mr. Trump and his allies of some of these same offenses.

The phone call between Mr. Trump and the Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger (“Fellas, I need 11,000 votes,” Mr. Trump demanded) is crucial evidence backing for a charge relating to soliciting a public officer to violate his oath of office. Mr. Trump’s coercive tactics persisted even though he should have known that Joe Biden fairly won the state’s Electoral College votes. But facts never seemed to matter. Mr. Trump’s false allegation of a rigged contest — a claim he and others made well before voting began — was grounded in a belief that opposition to his re-election was never legitimate.

Mr. Trump and his allies could not accept that an emerging multiracial coalition of voters across the state rejected him. Election deniers focused on Atlanta, a city whose Black residents total about half the population, as the place where Georgia’s election was purportedly stolen. The dangerous mix of racial grievance and authoritarian impulses left Trump loyalists feeling justified to concoct the fake electors scheme and imploring the General Assembly to go into a special session to arbitrarily undo the will of Georgians.

Political violence and intimidation are some of the most obvious symptoms of democratic decay. The charges in Fulton County are an attempt to use the criminal justice system to repudiate political violence.

The sprawling case is stronger because the conspiracy to overturn Georgia’s presidential election results was replete with acts of intimidation by numerous people. Mr. Trump and Rudy Giuliani engaged in a full-scale harassment campaign against Fulton County election workers when they baselessly alleged that two individuals added fake votes to Mr. Biden’s tally. Mr. Trump threatened Mr. Raffensperger and a state employee with “a criminal offense” if they declined to join his corruption, warning them they were taking “a big risk.” A healthy democracy cannot tolerate this behavior.

Democracy is not guaranteed, and democratic backsliding is never inevitable. The country avoided the worst, but the past few years have still been profoundly destabilizing for the constitutional order in ways akin to some of the nation’s darker moments.

Indeed, the case by Ms. Willis can be seen as an effort to avoid darker moments in the future, especially for a critical swing state like Georgia. We should remember the words in 1871 of Georgia’s first Black congressman, Jefferson Franklin Long, who spoke out when Congress debated relaxing the requirements for restoring certain rights to ex-Confederates without meaningful contrition: “If this House removes the disabilities of disloyal men … I venture to prophesy you will again have trouble from the very same men who gave you trouble before.”

His prediction proved all too accurate. It now may be up to the people of Fulton County to stop election denialism’s widening gyre.

Anthony Michael Kreis is an assistant professor of law at Georgia State University, where he teaches and studies constitutional law and the history of American politics.

Source photographs by Bettmann, Buyenlarge, and Corbis Historical, via Getty.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.