Oklahoma judge REFUSES to authorize reparations for victims of infamous 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre that killed ‘300’ black people after agreeing with city officials that claimants ‘don’t have unlimited rights to compensation’

- Lessie Benningfield Randle, 108, Viola Fletcher, 109, and her brother, Hughes Van Ellis, 102, are the last known survivors of the massacre

- Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the case earlier this month – after agreeing with city officials that the claimants ‘don’t have unlimited rights to compensation’

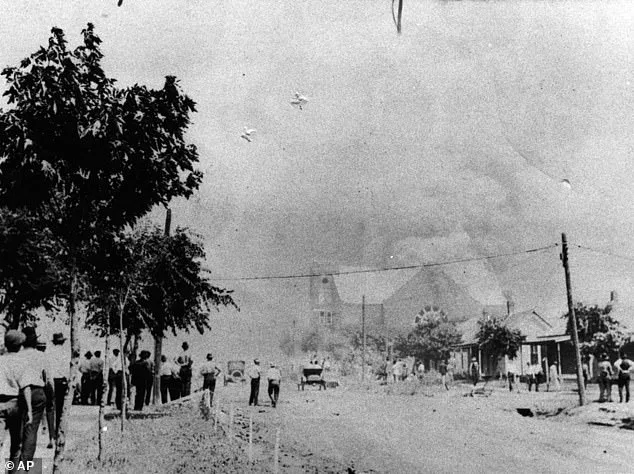

An Oklahoma judge has refused to authorize reparations for victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre which saw near to 300 black people get killed and have their livelihoods burned to the ground by a white mob.

Lessie Benningfield Randle, 108, Viola Fletcher, 109, and her brother, Hughes Van Ellis, 102, are the last known survivors of the massacre – and have been locked in a years-long legal battle to receive reparations.

Their lawsuit against the City of Tulsa sought financial and other reparations – including a 99-year tax holiday for Tulsa residents who are descendants of victims of the massacre in the north Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood.

Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the case earlier this month – after agreeing with city officials that the claimants ‘don’t have unlimited rights to compensation.’

It is estimated that as many as 300 people died in the massacre. It is one of the starkest examples of black wealth being decimated, leaving parents nothing to pass down and forcing generations to start from scratch.

The three plaintiffs have now vowed that they will ‘not go quietly.’

Damario Solomon-Simmons, their lead attorney and founder of the Justice for Greenwood Foundation, said he had not seen any document laying out Wall’s reasoning for her dismissal.

He called the lawsuit dismissal a ‘hurtful blow to our quest for justice’ and asked the federal government to open an investigation into the massacre.

Solomon-Simmons added: ‘We were forced to plead this case beyond what is required under Oklahoma standards, which is certainly a familiar circumstance when Black Americans ask the American legal system to work for them.

‘And now, Judge Wall has condemned us to languish on Oklahoma’s appellate docket. But we will not go quietly. We will continue to fight until our last breaths.

‘Like so many Black Americans, we carry the weight of intergenerational racial trauma day in and day out.

‘The dismissal of this case is just one more example of how America’s – and specifically Tulsa’s – legacy of racial harm, racial distress is disproportionally and unjustly borne by Black communities.

‘We will not rest until there’s justice for Greenwood.’

The attorney also told CNN: ‘They’ve waited 102 years trying to get justice and reparations for themselves, their families and our community here in Tulsa. And for me to get the phone call … I could not believe it. We were completely blown away.’

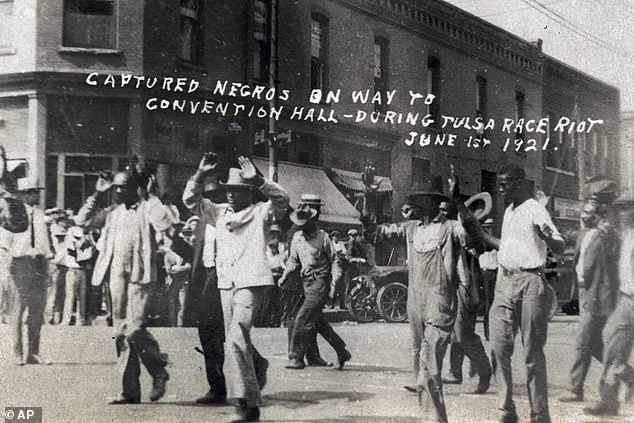

The violence in 1921 erupted after a white woman told police that a Black man had grabbed her arm in an elevator in a downtown Tulsa commercial building on May 30, 1921.

The following day, police arrested the man, who the Tulsa Tribune reported had tried to assault the woman. White people surrounded the courthouse, demanding the man be handed over.

World War One veterans were among black men who went to the courthouse to face the mob. A white man tried to disarm a black veteran and a shot rang out, touching off further violence.

White people then looted and burned buildings and dragged the black people from their beds and beat them, according to historical accounts.

The white people were deputized by authorities and instructed to shoot the black residence.

No one was ever charged in the violence.

Dr. Karlos Hill, a Professor of the Clara Luper Department of African and African American Studies at the University of Oklahoma, told KFOR: ‘I came really close to the history and the people who represent the history and certainly the victims, survivors and descendants.

‘So, the recent dismissal of their case, their claims, their rightful just claim for reparations for restitution [and] you’re talking about three known survivors, not all survivors…it’s been really disheartening to see that we don’t have a heart for these victims. We won’t find a way to to legally write or legislatively address [what happened].

‘When it comes to anti-Black racial violence, even the most the deadliest attack on a Black community, we still can’t find the compassion to give restitution to three survivors or even have a genuine conversation with the community about what a community reparations program today would look like.

‘A community was destroyed. And so if a community was destroyed, a community deserves reparations,’