Our “now-weary bodies have held on long enough to witness an America, an Oklahoma, that provides race massacre survivors with the opportunity to access the legal system.” — Statement by Lessie Benningfield Randle, 109, and Viola Fletcher, 109, before the early-April proceedings at the Supreme Court of Oklahoma.

“The Tulsa Race Massacre isn’t a footnote in a history book for us. We live with it every day, and the thought of what Greenwood was and what it could have been. We aren’t just black-and-white pictures on a screen. We are flesh and blood. I was there when it happened. I’m still here.” — The late Hughes Van Ellis’ statement to a House subcommittee in 2021.

In mid-October, Hughes Van Ellis, one of the three known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, died at 102. Earlier that month, Viola Fletcher, 109, and Lessie Benningfield Randle, 109, two of the last known survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, attended a hearing with House lawmakers in Oklahoma City. As of this writing, neither Fletcher nor Randle nor any of their descendants or other family members of those killed during the Tulsa 1921 race massacre have received any financial compensation.

In late February of this year, the Oklahoma Supreme Court announced that it would “allow oral arguments from the survivors’ legal team in April on whether to send their public nuisance case back to trial,” KWGS Public Radio Tulsa’s Ben Abrams reported. “Attorneys for the survivors argued Oklahoma’s public nuisance law applies to their clients because the massacre still has lasting effects for them and the Greenwood community to this day,” Abrams noted.

In early-October of last year, my daughter Leah from Massachusetts, friend John from Lawrence, Kansas, and I met up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. We had three goals: Visit the Woody Guthrie Center, the adjacent Bob Dylan Center (I know you’re already asking yourself why the Dylan center is in Tulsa!), and the Greenwood District (formerly known as Black Wall Street), the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

We spent an exhilarating day at the Guthrie and Dylan Centers – well worth a visit – and planned to visit the Greenwood District, the next day.

That evening, while leafing through a tourist guide, John discovered a description of the Greenwood Cultural Center and the Mabel B. Little Heritage House in the “Attractions” section of the 2022 Tulsa Guest Guide: produced by TulsaPeople Magazine:

In its glory days, Tulsa’s Greenwood District stretched for 35 blocks and was the largest and richest of Oklahoma’s more than 50 black communities — so wealthy, in fact, that Greenwood was known as ‘black Wall Street.’ Shops bustled by day and clubs wailed blues and jazz by night. Today, the Greenwood Cultural Center and the Mabel B. Little Heritage House — the area’s only home built in the 1920s that still stands — present a permanent history of the district.

The write up’s silence about the Tulsa Race Massacre was deafening.

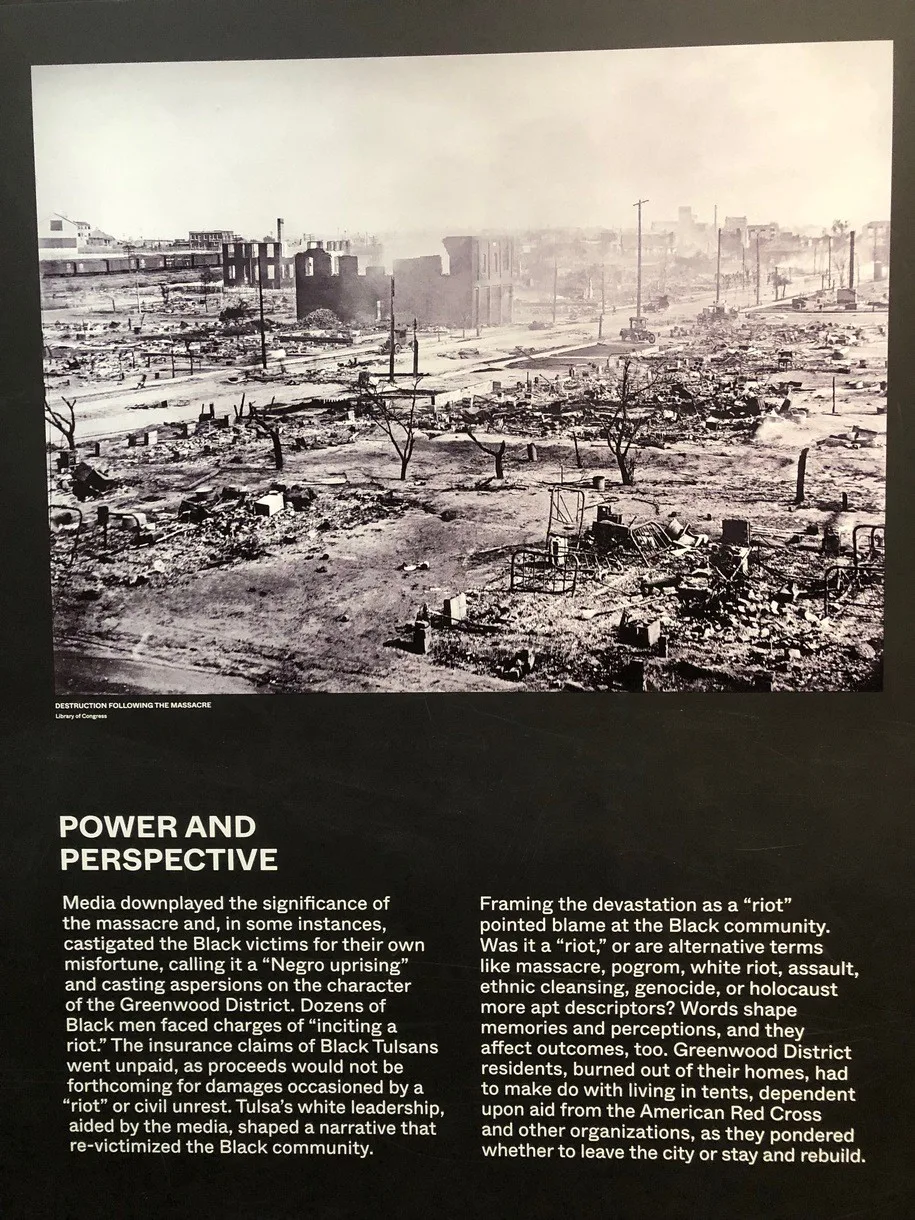

Two years ago, on the 100th Anniversary of the Tulsa White Riot/Tulsa Race Massacre, many Americans first learned of the atrocities committed by armed white vigilantes, with the tacit assistance of government officials, and support from a rabid media. Hundreds of people were murdered, thousands displaced, and Tulsa’s thriving Greenwood District was completely destroyed.

Many Americans only learned of this previously suppressed history because it was central to the stories of two hit television series: Watchmen and Lovecraft Country.

In the obituary for Hughes Van Ellis, Christine Hauser wrote (https://www.phillytrib.com/nyt/hughes-van-ellis-tulsa-massacre-survivor-dies-at-102/article_7a59b1fc-cbca-5406-a2a6-e68ed5b4cd64.html) of the events leading up to the White Riot.

On May 31, 1921, a Black man, Dick Rowland, was accused of sexually assaulting a white woman in an elevator in downtown Tulsa. After he was jailed, a group of armed Black people, fearful he would be lynched, gathered outside the county courthouse to ensure his safety.

Hundreds of white residents of Tulsa called on the sheriff to turn Rowland over and, according to a 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, a Black man’s gun went off when a white man tried to grab it.

The white mob spread out through downtown Tulsa, shooting Black people on sight and setting fire to businesses in Greenwood. The destruction eradicated a thriving district known as Black Wall Street, where Black entrepreneurs owned and ran restaurants, hotels, theaters and other businesses.

As many as 300 Black people were killed and more than 1,200 homes were destroyed.

The charges against Rowland were eventually dropped. The commission report said authorities concluded that he had most likely tripped and stepped on the woman’s foot.

Hauser reported that “In 2020, Van Ellis, Fletcher and Randle joined descendants of other victims of the massacre in filing a lawsuit seeking reparations for the losses they endured. Seven defendants were named in the lawsuit, including the city of Tulsa, the Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office, the Oklahoma National Guard and the city’s chamber of commerce. A judge ruled in May 2022 that part of the case could proceed. It was dismissed in July 2023, but the state’s high court agreed in August to hear an appeal.”

On October 6, Ellis’ sister Viola Fletcher, 109, and Lessie Benningfield Randle, 109, two of the last known survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, attended a hearing with House lawmakers in Oklahoma City. “The House Committee on General Government invited the survivors and other Greenwood descendants for an interim study exploring economic compensation for the victims and their relatives,” The Oklahoman reported.

In early November, The New York Times reported that “a team of lawyers representing Ms. Randle, Ms. Fletcher and the estate of Hughes Van Ellis — the younger brother of Ms. Fletcher who died at 102 in October — took what they consider to be the last legal step in their long quest for justice. They filed a final brief to the Oklahoma Supreme Court to consider whether an earlier dismissal [of a reparations lawsuit] by a district court judge, Caroline Wall, was proper. Should the court affirm the lower court’s dismissal, the case would be over. If the lower court’s ruling is reversed, the case would proceed.”

As of this writing, the survivors and their legal team are awaiting the court’s ruling.

The January 6 insurrection at the US Capital clearly demonstrated that white supremacy is alive and well in America. All too often, the crimes of white supremacy are relegated to seldom read history books. Currently, there are ongoing campaigns, led by right-wing politicians, think tanks, media outlets, and conservative organizations to sanitize school curricula and ban books, in transparent attempts to whitewash history.

The Tulsa Massacre is history that must not be forgotten; history that should not be glossed over in a local tourist magazine. Will the survivors and other families finally get justice? That decision now lies with the Oklahoma Supreme Court.