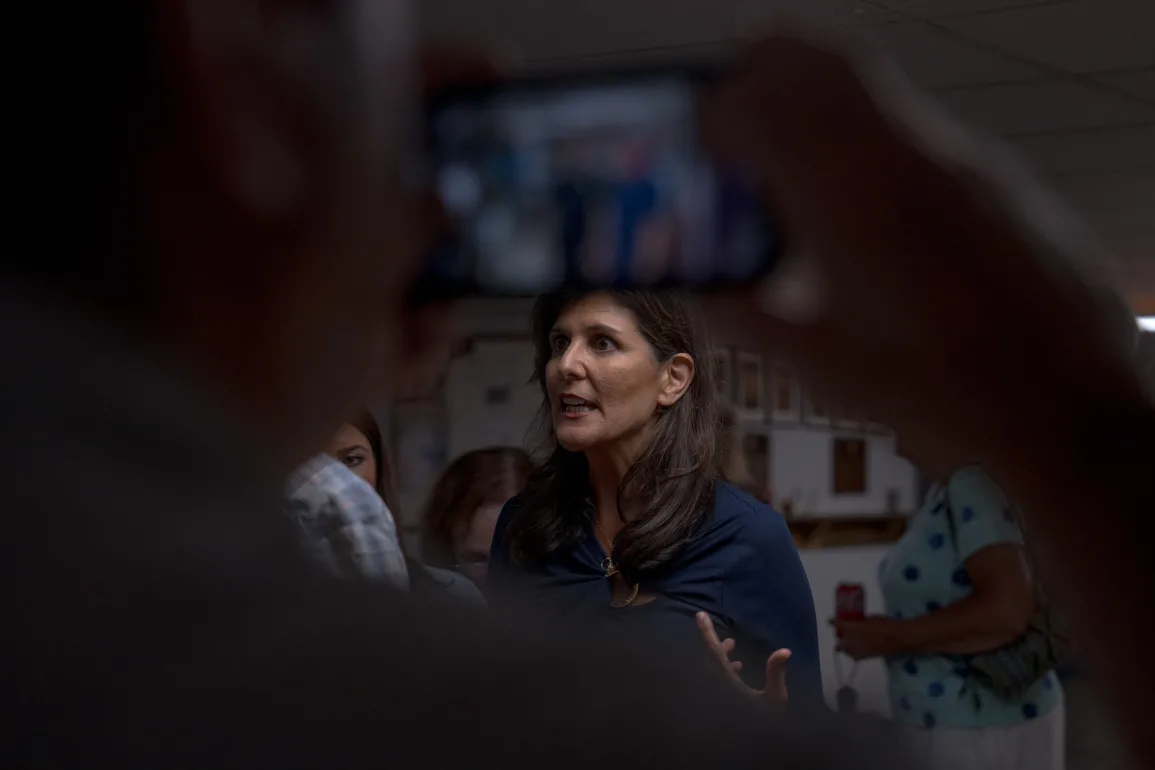

Nikki Haley’s Consensus Appeal

Midway through the Q.-&-A. section of Nikki Haley’s town hall, earlier this month, at the Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Merrimack, New Hampshire, a man named Ted Johnson stood up to announce that America was heading for civil war. “So,” he asked Haley, “how can I get back to that day, in the nineteen-eighties, when I was happy, running in the street, riding my bike?”

As it happens, Haley brings up the eighties a lot. Her most recent book takes its title from a Margaret Thatcher quotation, and she frequently invokes Thatcher on the campaign trail; last month, at the first G.O.P. Presidential debate, she trotted out the “If you want something done, ask a woman” line to her biggest audience yet. In February, a video teaser for Haley’s campaign had opened with a grainy clip of Jeane Kirkpatrick—the Democrat turned neocon foreign-policy adviser to Ronald Reagan—addressing the 1984 Republican National Convention.

In the course of the very long U.S. Presidential-campaign season, most candidates are usually furnished with an opportunity to have “a moment.” This is Nikki Haley’s: CNN’s most recent general-election trial heats show her beating Joe Biden by the biggest margin of any Republican candidate, including Donald Trump. After the first debate, which, as the Washington Post put it, Haley “won on brains and experience,” David Brooks wrote that it was time to “give Haley her chance”; even The New Republic had a piece about why she “scares the Biden campaign.” Haley doesn’t present as an isolationist or a populist; she doesn’t call the government “the regime” or compare the country to the Roman Empire in decline; at her events that I attended, she never said the word “woke,” or even “liberal” or “élites.” She favors the cliché “I’ve always spoken in hard truths,” a simple bromide that manages to distinguish her in the non-Trump G.O.P. primary lineup—not haranguing like Ron DeSantis or Vivek Ramaswamy, not as lifeless as Mike Pence’s comparable appeal to the golden age.

At the Veterans of Foreign Wars post, a flashing sign at the entrance advertised a meat raffle. A former Air Force nurse had introduced Haley, who paced in flared bluejeans and a white lace sweater. When Johnson asked her how he could get back to the eighties, she took his disillusionment and wistfulness for a bygone era as an opening for a poignant yarn—the kind of story that Democrats usually tell—about a daughter of immigrants burying the Confederate flag.

“I don’t know if y’all remember, we had a horrific church shooting in South Carolina a few years ago,” she said. She recounted how, in 2015, a young white man had murdered nine Black churchgoers at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in Charleston, after participating in a Bible study with them. The shooter’s writings called for a race war, and his Web site included photos of him with the Confederate flag; Haley decided it was time for South Carolina to take down that flag from in front of the statehouse, where it had flown since 1961. To persuade state lawmakers to vote in favor, Haley said, she told them about accompanying her father, a Sikh who taught at a historically Black college, to buy groceries on an excursion from the small town where they lived; the shopkeepers called the police when they saw her father’s turban. “Every time I have to go to the airport, I have to pass that produce stand. And, every time I pass it, I feel pain. Don’t make any child have to pass the statehouse and see that flag and feel pain.”

After the town hall, I sat in a folding chair next to Johnson. “I was for Trump in 2016 and 2020, but now I want unity,” he told me. “I’m a Haley convert. I ordered her sign last night. Right now, I have one up for Burgum, but that’s coming down.” I told him that I thought I saw him tearing up during Haley’s riff about the flag. “I had totally forgot about that,” he said. “She was the one who actually got it taken down—she worked with Republicans, Democrats, faith leaders, community leaders. When I say the nineteen-eighties, Mom let me out of the house and I didn’t come home until dark. Everybody liked each other, everybody was happy. Me and my wife are Independents now, and Haley’s going to pull in people like us. She’s going to pull moderate Democrats, too.” He went on, “You got a lot of that Trump base right here, in the backwoods. They want Hunter to pay, they want Hillary to pay. That ain’t moving our country nowhere.”

“Do you remember, when you were growing up, how simple life was, how safe it felt?” Haley had asked the crowd, which applauded as she walked off to “American Girl,” by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. “Don’t you want that again?” They did, and they do. Haley said that she raised a million dollars within seventy-two hours of the first debate, and her campaign swing through New Hampshire had a triumphant tone. During her town halls, I noticed audience members using her phrasing unprompted. (“I’m here because of the debate,” one voter said, “and you told hard truths.”) Melinda Tourangeau, a Desert Storm veteran in pearls, pink lipstick, and a striped blazer, told me, “I haven’t loved a politician this much since Ronald Reagan.”

Haley’s pitch for the future harks back to a more traditional vision of the G.O.P.—the type of candidacy one might think the contemporary Party would have no use for—but a canny establishment conservative may be Biden’s greatest threat. Haley is now tied with DeSantis for second place in the New Hampshire primary polls—Trump, of course, is first—but, more significant, she seems to hold real appeal for a swath of moderate suburban voters whom Biden needs to win. She took down the Confederate flag, isn’t forthrightly hostile to transgender rights or a woman’s right to choose, and sides with liberal internationalism in her support for Ukraine. She’s the first female minority governor in the country, and she’s never lost an election. Her pitch is notably inclusive: “We should want to win the majority of Americans,” she said. “Our solutions are the right ones, but you don’t do it by pushing people away. You do it by opening the tent. We need more people in. We need young people, we need women, we need African Americans, we need Asians, we need Hispanics. And you don’t go to them and say, ‘You should be with us.’ You go to them and say, ‘What do you care about?’ ”

The day before the V.F.W., Haley had been in Claremont, a formerly prosperous mill town by the Vermont border, for a town hall in the game room of a local senior center. A license plate pinned to the wall read “Retired: No Worry, No Hurry, No Phone, No Boss.” Nearby was a sign warning people not to fall for scams; dinner, according to a menu written in cursive on a whiteboard, would be shepherd’s pie. Haley walked in wearing a blue striped blouse and white, open-toe espadrilles that showed a light-pink pedicure. The event was small; there weren’t more than ten attendees per reporter.

Haley usually opens her stump speech with an abbreviated family origin story: the only Indians in a two-stoplight South Carolina town—“We weren’t white enough to be white, we weren’t Black enough to be Black”—where her parents told her how blessed they were to be in America. She talks about dropping off her husband, a combat veteran, at four in the morning for a yearlong deployment to Africa. She points out that, before politics, she was an accountant who graduated from a public university. (No law school, no Ivy League.) She always says, “The first thing we’re going to have to tackle is this national self-loathing that has taken over our country”—a callback to Kirkpatrick’s “Blame America first” speech, in which she said that the American people understand “the dangers of endless self-criticism and self-denigration.” Haley likes to conclude by insisting that she’s glad to have been underestimated for her entire life: “It makes me scrappy.”

She also musters bits of jovial, canned banter without inducing the cringe of Pence or DeSantis, or, for that matter, the current President. She makes an attentive, active-listening face, smiles, and doesn’t interrupt; she stopped mid-sentence to say “Bless you” to someone who sneezed in the back of the room. She held a voter’s crying baby and stayed late to talk to the local cops manning the event. Two women next to me debriefed: “That was great—someone who actually accomplished something.” Two school-age kids wanted Haley’s autograph, and, when they got to the front of the line, she knelt down to confer with them at length before signing “God bless you” into their notebooks.

G.O.P. events in New Hampshire aren’t just attended by Republicans looking for a post-Trump candidate; many of the audience members were Democrats and Independents listening closely to see if they could find an alternative to Biden. At the town hall in Claremont, I talked to Barre Pinske, who wore turquoise, horn-rimmed glasses. “I’m an artist, a sculptor, so I should be a Democrat,” he said. “I like Obama and Reagan. Obama was cool, he could ride around with Jerry Seinfeld, and Reagan was a man’s man. I’m not married and I don’t have kids, but I have family values. All that sort of stuff matters to me. So just because I’m a free spirit, I still have a nostalgic, American kind of perspective.” He went on, “The Republican Party is messed up, and, if someone doesn’t come in as more centrist, the Republicans have no chance to win. I would like to see them get somebody who can get those swing voters. I’m the kind of voter they’re looking for, and I’m drinking the Haley Kool-Aid.”

Haley is the only female candidate in the G.O.P. primary, a fact that many voters in New Hampshire told me, unbidden, they were drawn to. When Haley declared her candidacy, back in February, Don Lemon was benched from CNN for saying that, at fifty-one, she was “past her prime.” (Afterward, Haley said that she raised twenty-five thousand dollars for her campaign by selling beer koozies that read “PAST MY PRIME?”) Pinske told me, “She brings a maternal spirit to a leadership position.” Haley mostly comes across as hawkish and tough, but she does occasionally embrace a certain maternal energy. Of South Carolina, post-shooting, she said, “I had to put my arms around my state and protect her.” Later: “I think we need a mom in the White House.”

At the Vets post in Merrimack, her hawkishness had the crowd cheering. A man named Paul in an American-flag T-shirt told me, “I want somebody willing to pull the nuclear trigger with China. Get it over with, even if it would be the end of us. Margaret Thatcher, Golda Meir—we need somebody tough.” Haley’s international experience appeals: a former Army nurse named Barbara Healey said, “We could have Russia, China, North Korea banging on our door—we need someone who can deal with that.” The audience loves when Haley says that being the U.N. Ambassador allowed her to take the “Kick Me” sign off America’s back. I wondered how her interventionist policy in Ukraine would play, given that Trump, DeSantis, and Ramaswamy all want less U.S. involvement. She pitched giving weapons and money to Ukraine as a short-term patriotic duty; a quick end to the war would keep veterans like her husband from going to fight, and be a display of strength to China and Russia.

When asked about post-Roe America, Haley responds with a display of equivocation that avoids alienating most pro-life voters while also managing to bring in liberals. “I’m going to tell you my hard truth, because I don’t think Americans get the truth on this situation,” she said, in Merrimack. “I don’t judge anyone who’s pro-choice.” She mentioned a college roommate who was raped; she talks about her husband’s adoption and her own difficulty conceiving. Haley’s appeals to consensus—“Can’t we all agree?”—save her from the extremes that would lose her votes, but also reveal to some a crucial lack of conviction on issues that should define her. “The paradox is that she says all of this stuff, but she’ll still campaign and vote for Trump when it comes to it,” Stuart Stevens, a former Republican political consultant, told me. “This is somebody who has courted and said positive things about the most right-wing elements of the Party. The differences between Haley and Marjorie Taylor Greene are ultimately purely aesthetic, but I don’t think M.T.G. is reading polls to remind her of her deeply felt beliefs. There’s a frivolousness to Haley running for President and trying to please everybody.” Haley frames this differently, as a “story of addition.” Shortly after announcing her candidacy, she told Bari Weiss, “There’s a reason that I’m more likely to win a general election than anyone else. It’s because I identify with so many different people.”

After the Vets post, Haley visited the Founders Academy, a charter school in Manchester, to do a town hall with Tiffany Justice, a founder of the conservative advocacy group Moms for Liberty. Beforehand, she sat at a roundtable with the school principal, some teachers, and a couple of moms running for the local school board. In the sweltering classroom, a poster with an inspirational quote—“Life Is Tough, My Darling, but So Are You”—hung next to the works of Shakespeare arranged by color. One of the moms at the table fanned her baby with a pocket Constitution. Haley kept it boring. “We don’t want Democrat and Republican parents,” she said. “We want all parents. Don’t all parents want transparency?” During the town hall, held in the school library, a press photographer sitting on a shelf crashed through it, sending colored pencils flying everywhere. Haley told a story about how, when she was in seventh grade, her dad didn’t sign her sex-ed permission slip, so she had to sit in a room alone during the course. “That’s not for the schools to decide,” she said.

Haley said that Biden had called her out as a “MAGA extremist” for doing an event with Moms for Liberty. “Then count me as one of them!” she joked. She presented as traditional, not extreme, making all the points that conservatives want to hear without devolving into a full-time battle with Disney or promising to abolish the Department of Education, in the bellicose vein of DeSantis and Ramaswamy. She managed the same thing with transgender questions as she did with abortion, at times coming across as almost progressive compared with most other G.O.P. candidates. “I believe in freedom,” Haley said. “If an adult decides that they want to transition, they are welcome to do that.” (Recently, even Trump seems to sense danger in taking uncompromising positions on these matters: he called DeSantis’s abortion ban a “terrible mistake” and told Megyn Kelly that he’d heard a man can now give birth.) At the senior center, Haley had reminded the crowd that Republicans have lost the popular vote in seven of the past eight Presidential elections, and that seventy-eight per cent of parents don’t think their children will have a better life than they did. By acquitting herself with Moms for Liberty while toeing a moderate line, her subtle rebuttal of Biden was the idea that this all could be simple again, not a forever war between progressives and extremists. Haley shared an anecdote that she often rolls out on the campaign trail, recalling her mother’s advice to her when she was teased in school for being Indian: “Your job isn’t to show them how you’re different. Your job is to show them how you’re similar.”

In Claremont, during a Q. & A., a voter named Dale Giles mistook Haley for Tulsi Gabbard. After Haley clarified that she wasn’t, Giles still launched into his critique: “It seems like you have an axe to grind with Trump. I’ve got nothing but the utmost respect for you.” Giles wore a Dodge hat and a shirt styled to resemble the Walmart label that read “Biden: Pay More. Live Worse”; his cell phone was ringing loudly in his pocket. He had more of a comment than a question, concluding by suggesting that Haley pick South Dakota’s governor, Kristi Noem, as her running mate. (“I think that means you’re a fan of women!” Haley responded.) Afterward, Giles went up to take a photo with Haley, and they spoke for several minutes. I asked for his impression of the candidate who minutes ago he thought was somebody else. “I’d love to see Joe take her behind the barn,” he said, smiling and pausing for effect as I waited to see where he was going with it. “And let her kick his ass.”

Even if Haley has the best chance against Biden, it doesn’t mean that she’ll be the Republican nominee. (In New Hampshire, being tied for second with DeSantis still means that they’re both losing to Trump by thirty-seven points.) To the base “in the backwoods,” as Johnson, the eighties nostalgist, calls the MAGA hard-liners, Haley is the archetypal striving representative of the globalist, anti-populist, corporate wing of the Party. In a Times roundtable called “Nikki Haley Will Not Be the Next President,” Daniel McCarthy, the conservative columnist, wrote that she is “too representative of the party elite’s desires to be seen as a plausible tribune of the working class.” (At the debate, Ramaswamy wished Haley well in her “future career on the boards of Lockheed and Raytheon.”) She’s clearly sensitive to this flaw in her image as a candidate; on a podcast, asked to name the last book she had read, she offered “Hillbilly Elegy,” by J. D. Vance. “Nikki is running for an endowed chair at the Atlantic Council, not a Presidential nomination,” Tucker Carlson told me. “She’s not trying to win Trump voters. She’s doing something stealthier and more difficult, which is to make professional-class Trump haters forget that, just a few years ago, she worked for him. How many other Trump Cabinet secretaries would the average NPR listener conceivably vote for? Nikki’s the only one.”

Haley is gently pitching herself as the one to move the Party beyond Trump—“We have to elect a new conservative leader”—without denouncing him too much, but, in Claremont, she was dogged by demands to articulate her allegiance to the former President. “People are wondering if you were lying when you raised your hand at the debate to say you would support President Trump even if he was in jail,” Giles said. “Can you raise your hand with us now to say that you would support President Trump?” Haley is nimble at pivoting when it comes to what may be the most consequential stance in this race, for those who actually want to win—the precarious Trump line. She reminded voters that she was able to leave the Trump Administration “without a tweet,” dignity intact. Great as the eighties may have been, Haley’s pragmatic equivocation might be her best weapon; she understands the “hard truth” of the one real deciding factor about whether a moment can last. Her way out of the yes or no, hand up or down for Trump? “I speak hard truths,” she replied, smiling. ♦