In her new role as the executive director of the Deuces Live, St. Pete native Latorro Bowles has plans to revitalize the 22nd Street corridor.

BY KILEY WOODS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – Twenty-Second Street, known to some as The Deuces, has the art but needs businesses and people to return to the historically Black corridor in south St. Pete. Today, about 10 Black-owned businesses remain on the street, but it does not come close to what was once called St. Pete’s Black Wall Street.

St. Pete native Latorro Bowles knows the corridor, the history, and the colorful stories of the past. She’s working to revitalize the strip in her new position as executive director at The Deuces Live. The board of directors selected Bowles to help usher in a new era.

She’s working to bring in new businesses, parking, and affordable housing. She wants visitors to feel energized in the company of history, art, and the once soul of the Black community.

“When The Deuces Live was founded, there were hundreds of businesses on the corridor, so my goal is to bring those businesses back,” Bowles explained.

At the inception of The Deuces Live in 1962, its vision was to revitalize the community while preserving its heritage, and today, the non-profit’s mission is the same, except it’s also tasked with the mission to resuscitate the area.

“People used to love The Deuces as a place to live, work, and raise their families, and residents who have lived there for 30 or 40 years want to see the community back thriving,” Bowles stated.

During Jim Crow St. Pete, African Americans could only occupy a small portion of the city. Twenty-Second Street became a town within a town. Places to buy groceries and clothing sprouted. Black people opened medical and law practices, funeral homes, restaurants, entertainment outlets and beauty salons.

“The neighborhood to me means family,” Bowles said. The neighborhood also means connection, history, heritage and stories of segregated St. Pete.

The Royal Theater, 1011 22nd St. S, served the Black community from 1948 to 1966. Pictured, owners and staff preparing for opening night, Nov. 23, 1948.

The Deuces Live and the Warehouse Arts District devised an action plan in 2018 to revitalize the corridor. The first step is to engage the public with the community through trolley tours, public meetings, workshops and stakeholder meetings.

The second step is to build up the main corridor: finish the walkable spaces, make 22nd Street and Fifth Avenue South livable, and use design to express art, culture and the corridor’s history.

Bowles hopes to build the street back up to what residents remember and love about the once safe haven. When 22nd Street was the heart of the Black community, it was a safe space for Black people to create an identity far removed from the oppression that was embedded in St. Petersburg’s social construct.

The corridor looks different now from its once bustling life. When the highway came barreling through, businesses, homes, and churches were displaced or destroyed, and the close-knit, self-sustaining community was lost.

Bowles wants people to remember what it felt like to come home.

Colorful murals offer a glimpse of the entertainment residents enjoyed when the community flourished. Zulu Painter’s ‘JAZZ’ was created in 2016.

The sounds of jazz once slugged through the muggy Florida heat. Now, colorful murals offer a glimpse of the entertainment residents enjoyed when the community flourished. The murals are there, but the busy streets are a distant memory.

Louis’ Satchmo’ Armstrong takes a break from a Manhattan Casino gig in the company of two fans, Josephine Smith (left) and Ester Peck Thomas.

“In 1962, it was the heart of the African community in St. Pete,” Bowles said. She wants people to be excited to return to the Deuces.

In 1962, over 100 businesses thrived on the corridor. There were flower shops, a dentist’s office, banks, doctors, clubs, lawyers, a hospital and private residences. Over 75 percent of the businesses were owned by African Americans seeking their own space in a heavily segregated city.

In the 1950s and 60s, the corridor was hopping with live music. A famous stop on the Chitlin’ Circuit, Black musicians, such as Count Basie, Cab Calloway, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, Fats Domino, Bobby Blue Bland, Ella Fitzgerald, Ike and Tina Turner, Dinah Washington, Duke Ellington, Della Reese, Otis Redding, Ink Spots, Little Richard, Booker T and the MGs, Sarah Vaughn, Lionel Hampton and James Brown — to name a few — had the walls of the Manhattan Casino vibrating.

For those not lucky enough to get in to see one of those famous acts, there was always Sno-Peak walkup restaurant across the street where the music from the Manhattan would spill over, acting as an outdoor auditorium.

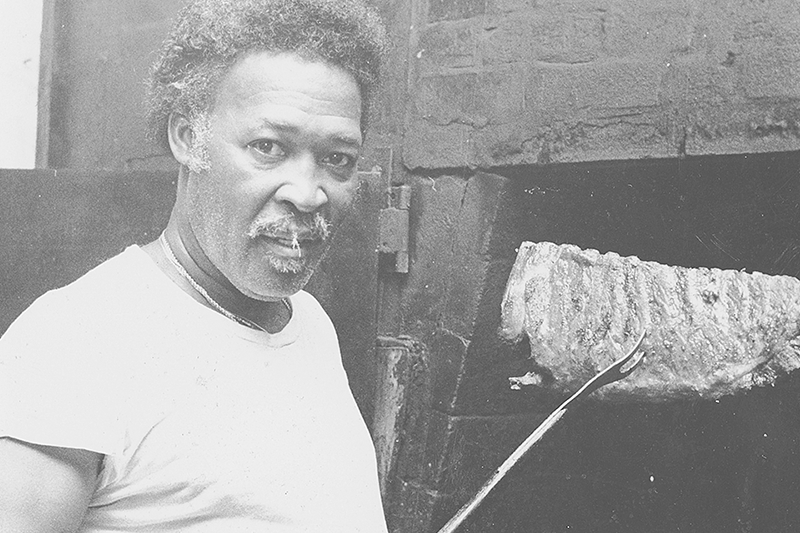

Also, Geech’s BBQ catered to late-night crowds leaving the Manhattan Casino, and it was also a favorite lunch spot. Students would often save their lunch money and stop by after school for some ribs or a ham sandwich.

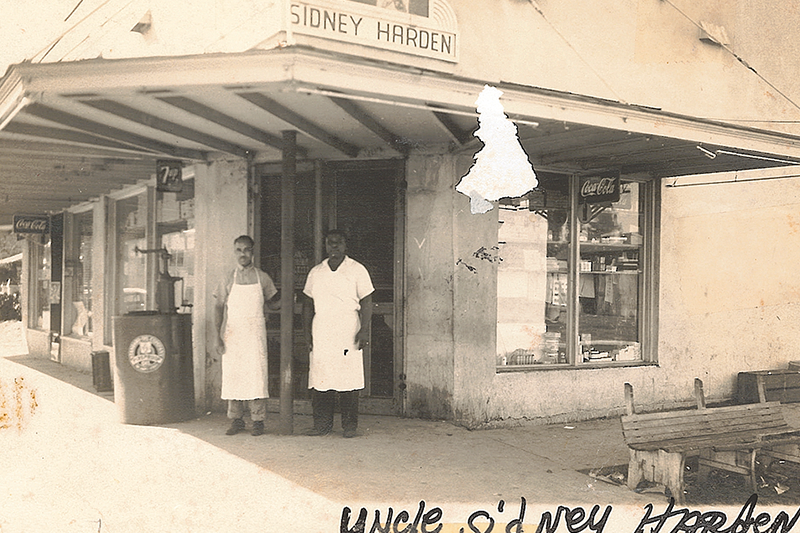

John ‘Geech’ Black opened Geech’s BBQ in the 1930s and had several locations along The Deuces before he sold it in 1973. The new owner kept the name until it closed in the early 1980s.

“It had a down-home feel when you would drive through the corridor,” Bowles said.

Despite the community’s strength, it could not stave off social change. Integration, the coming of I-275 and the reality of urban redevelopment fragmented the neighborhood and caused the residents to scatter.

“Changes in and around the community in housing and development, a lot of residents have had to leave, and the businesses too, leading to community decline,” Bowles averred.

The new executive director wants to build up the brand and the wealth in the community. Bowles believes The Deuces has just become a name, but she wants the name to shine again.

“We have our new Deuces Corner Park with a small pavilion and bandshell across from the Deuces Live office. I plan to add additional benches, street lighting and other minor amenities that promote usage along the corridor,” Bowles shared.

Now, 22nd Street South is vulnerable to redevelopment and gentrification, but Bowles feels working with community leaders will help return the street to its former glory.

How did 22nd Street become a Black Wall Street?

On a November night in 1921, two explosions rattled the Dream Theater, a new movie house on Ninth Street South for St. Pete’s Black residents. Someone had bombed it. No one was hurt, but the message was as loud as the blasts. The St. Petersburg Times report said: “The theater was blown up because white residents of the section … objected to the Negroes congregating in the place.”

The theater closed, and, as so often happened in the decades that followed, Black residents were pushed out of the way. On what was then the edge of a growing city officially not quite three decades old, African Americans began to create a community of their own along a dirt trail called 22nd Street South.

Surrounded by pine trees and palmetto bushes, it was the country, part of a sprawling tract the city government had recently annexed. Eventually, 22nd Street became one of the nation’s African-American main streets – a smaller version of such promenades as Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn, Beale Street in Memphis or Ashley Street in Jacksonville.

Source used: “St. Petersburg’s Historic 22nd Street South by Rosalie Peck and Jon Wilson.”