By Nicole S. Daniel

The Birmingham Times

Black journalists face a unique set of challenges that include disruptions in the industry, objectivity when it comes to covering race or social justice issues, managing emotions, and often working in majority-white newsrooms.

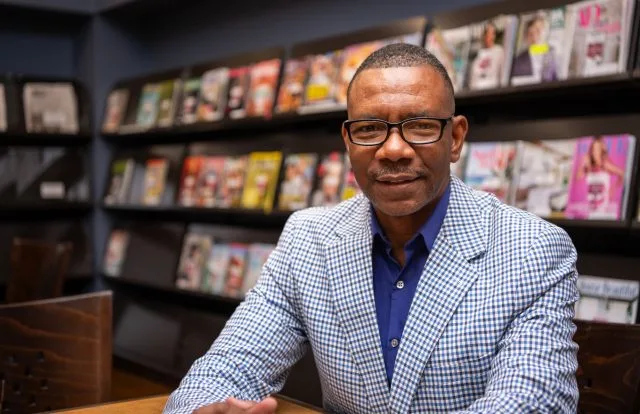

Those were among the topics Birmingham journalist William “Bill” Singleton researched in his dissertation for his recently obtained Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree, from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

“I interviewed Black journalists, [22, including 11 men and 11 women], to find out how they negotiated and handled both objectivity and their emotions and what they see as their roles, as well as to understand the impact that organizational structure has on their reporting and writing of topics that deal with social justice or race,” said Singleton, a former journalist with 26 years of experience in the field, including positions at The Birmingham Post Herald and The Birmingham News, both of which have ceased printing.

Singleton will be attending the 2023 National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) Convention and Career Fair, which is being held in Birmingham from August 2–6. During the event, he plans to network, make contacts, and track the latest developments in the industry.

Working Through Trauma

Working in the field of journalism can take a toll on the mental health of any journalist, especially Blacks, said Singleton during a recent interview with The Birmingham Times.

“We have felt the trauma, but we are still going to work,” he added. “Black journalists in a changing journalism field have to negotiate objectivity and emotional labor.”

Objectivity and emotions were a key part of Singleton’s research.

“I wanted to find out how objective a journalist can be when it comes to covering race or social justice and how they manage their emotions,” he said. “Objectivity traditionally [involves being] nonbiased and addressing both sides, demonstrating fairness and detachment. Number one, that’s hard to do; you have to train yourself to do it. Two, is that really how you feel? Three, there is a perception that African Americans have to do that while white reporters don’t.”

He added, “White editors build their understanding into news and news coverage. Their perspective is not seen as biased. There is perception versus reality.”

In terms of emotional labor, he asked, “How do you manage your emotions?”

“Emotional labor is [a component] of every profession because each one has certain requirements for their professionals and how they respond emotionally,” Singleton explained.

“In many critical situations, most journalists remain calm. But how do they really feel? Because of objectivity, journalists are taught to be detached and emotionless,” Singleton said, adding, “How does one really feel and practice that?”

For example, Singleton said there were some stories he couldn’t do or would ask to have his byline removed from because “earlier in my career, I didn’t want to be associated with some stories.”

“What’s Going On Vs. How You Feel”

Asked about ways for journalists to take care of their mental health, he referred to his dissertation.

“It’s interesting that most of the women that mentioned emotional labor talked about mental health and working for companies that are concerned about their mental health,” he said.

“For journalists, it’s been about covering what’s going on and not how you feel. Journalists cover tragedies and the impact they have, [and that can be] taxing and mentally exhausting. Based on my research, many of the journalists that work at legacy newspapers use their vacation time and also use mental health resources. For example, some [radio] stations will give a certain number of days for journalists to take off or they offer services, [such as providing help to] seek a therapist.”

Singleton says his research builds cases for monitoring how many Black journalists face mental health issues due to the job. He said journalists are not immune from some of the mental health issues we read about.

“With all that’s going on in society today dealing with mental health, it’s interesting that when you have these mass shootings and when they apprehend the suspect and delve into their background, they find that the person suffers from mental issues. That’s a big thing, and I don’t think reporters or media organizations can avoid that. These things are happening regularly,” he said.

Further Research

Currently, Singleton is looking forward to becoming an assistant professor at Samford University in the fall, in addition to conducting additional research. As for his 182-page dissertation, he’d like to see it published as sections in journals.

“I probably can get four or five [sections] from my dissertation,” he said. “That would look like ‘Black Journalists and Objectivity,’ ‘Black Journalists and Emotional Labor,’ ‘Black Journalists and their Role in Covering Social Justice and Race-Related Issues,’ and ‘Black Journalists and the Structures That Dictate Their Coverage.’”

He also wants to delve into how Black people are represented in the media as journalists and gatekeepers, as well as in images in media and the audience reaction.

“For example, I did a yet-to-be published paper that entails me looking at comments on social media when there is a Black criminal suspect and when there is a white criminal suspect.”

Singleton found that when the suspect is Black suspect, there is a thread of racial comments. When the suspect is white, however, those types of comments are rarely made.

“The study shows that people say they don’t focus on race, but they do,” he said. “I’m interested in that and also how that manifests itself on social media.”

An Epiphany

Singleton was born in Washington, D.C., and raised primarily in Maryland with his older sister, Kim, and younger brother, Marc.

“I was a part of the desegregation of schools,” he said. “We went from an all-Black school to integrated schools, and that was an issue.”

To further his education, Singleton says it was expected of him to attend college. Both his parents attended Historically Black College and Universities (HBCUs). His father attended Morehouse College, in Atlanta, Georgia. His mother and siblings attended Howard University, in Washington, D.C. After Singleton graduated from Central Senior High School in Capitol Heights, Maryland, he attended Hampton University, an HBCU in Hampton, Virginia.

“I wanted to get away from home,” he said. “I had lived in Washington, D.C., all my life, and I wanted to experience another state but not be too far away. I remember seeing an informational brochure from [Hampton University] that featured a person at a radio station on campus.”

At the time, Singleton knew he wanted to pursue the field of communication but didn’t know exactly what he wanted to do.

“I didn’t even know if I wanted to be a writer,” he said, adding that he attended college with one thing on his mind—education.

“In high school, I passed but didn’t study. Then I had an epiphany: I wondered how I would do if I really studied. That’s the mindset I had when I went to college. I didn’t party, so I wasn’t distracted by a lot of things,” said Singleton, who graduated eighth in his class.

Though he didn’t involve himself in the party scene, he was involved in campus activities. He became an announcer for the school’s basketball teams and wrote for the student newspaper, the Hampton Script.

“I would write about musicians and speakers that came to the school, too,” he said.

Still, Singleton never imagined a career as a reporter.

In 1985, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mass media arts and looked for jobs, most of which required him to have a lot of clips, an old journalistic term for taking newspaper clippings and placing them in the professional portfolio to showcase the applicant’s published work.

“A lot of mass media majors wanted to go into law. I could have because I had the grades, but I didn’t want to sit at a desk,” said Singleton, who eventually secured an internship at the Detroit Free Press as a copy editor, someone who reviews text to correct grammatical, punctuation, and spelling errors, as well as ensure that it adheres to the publication’s conventions for style and tone.

“I didn’t like it because I was confined to a desk,” he said. “I wanted to get back to reporting. With reporting you work at a desk, but you get out and meet people. That appealed to me more.”

“A Different Experience”

Singleton learned about a position at The Birmingham Post-Herald, one of the two daily newspapers in the city at the time. (The other was The Birmingham News.) He applied, was offered the job, and moved to Birmingham in 1986. He remembers that Birmingham “was a different experience.”

It took Singleton about a year to adjust to the newspaper’s style of journalism. As a general assignment reporter, he learned the importance of calling individuals and getting the correct information for his articles. That training made him well-rounded and equipped him for covering his beat, or specific area of coverage, which included Birmingham City Hall, Jefferson County government, and the neighboring cities of Hoover and Vestavia Hills.

“Because we were a small paper, we could do a lot of things. Our circulation wasn’t as large as The Birmingham News,” said Singleton, who worked with the Post-Herald until September 2005, when the paper stopped publishing.

He then joined The Birmingham News. He remained there until 2012, which is when he decided to shift gears career-wise.

“I was done with journalism full-time, though I did some freelance [writing] for several publications,” said Singleton, who took a position at Mercedes Benz U.S. International, just outside of Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

His role as an internal communications specialist involved generating one-page synopses, or summaries of information, for plant workers, among other responsibilities—but journalism beckoned.

Singleton had an interest in becoming a professor and conducting research, so in August 2018 he enrolled at the University of Alabama to earn a master’s degree in journalism and creative media. He found that the school offered a dual master’s-doctorate program and thought that would be a better fit. He completed his studies at the University of Alabama in May 2023 with his Ph.D.

Besides reading, writing, and doing research, Singleton spends time with his wife, Nichole, and sons, Will and Cam.

Asked why it’s important for a Black journalist to stand out Singleton said, “We’ve always had to be twice as good. You have to be better because there’s still a perception that you’re not qualified. The other part is we bring our living experiences. We [often] make up the audience that we have to represent.”

Meet Phyllis Gilchrist, a Birmingham native who helped found the city’s chapter of the NABJ. Click here

Read about Nathan Turner Jr., the University of Alabama’s first Black undergrad in journalism. Click here.

The 2023 National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) Convention and Career Fair takes place in Birmingham, Alabama, from August 2–6. Thousands of Black journalists from across the United States will be in attendance.